Why Is Sugar Bad For You? Proposed Warning Labels For Soda Could Quell Consumption

A mother pulls a bottle of soda off the shelf at the grocery store. It's nearly in the shopping cart when something catches her eye. On the label is a detailed warning about just how bad the main ingredient, sugar, is for the body. She returns the soda to its place and walks away.

Or so public health officials are starting to dream.

As the U.S. grapples with epidemic levels of diabetes and obesity, legislators, public health officials and advocates are increasingly experimenting with ways to discourage people from buying foods and drinks loaded with added sugar, which has been linked with these diseases and a host of other health problems. One tactic, adding warning labels about the harmful health effects of sugar, could help deter parents from buying such drinks, a study published Thursday suggests. Yet as the battle against Big Soda heats up, experts say it will take far more than warning labels to change what people put in their grocery carts and finally put the brakes on rising rates of lifestyle-related illnesses.

"I don’t think anyone would say that a warning label could be a silver bullet for obesity," said Christina Roberto, an assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine and co-author of the new study, which was published in the journal Pediatrics.

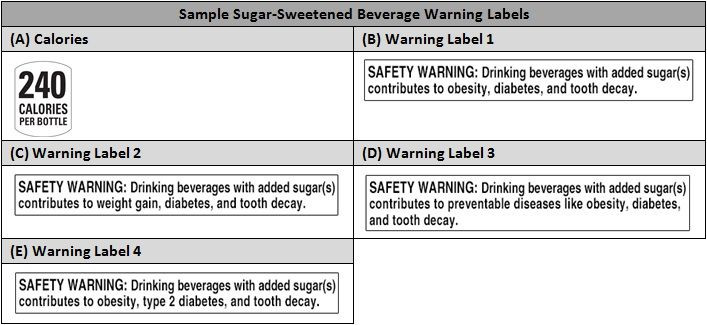

The study, which surveyed 2,381 parents online, was one of the first to look at the impact of health warning labels compared to simple caloric ones. On average, parents were 20 percent less likely to buy a sugary drink after reading a health warning than if they did not see such warnings, the study found.

Every year, 1.4 million Americans are newly diagnosed with diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association. The total cost of the disease, from direct medical costs to indirect ones like disability or premature death, reached $245 billion in 2012. More than one-third of American adults suffer from obesity, which has estimated annual medical costs of $147 billion.

The causes of obesity and diabetes are widespread and vary among individuals, from genetics to diet and exercise habits. But a growing body of evidence links drinking sugary drinks like soda, fruit drinks, tea and energy drinks to weight gain, obesity and the development of Type 2 diabetes, an increased risk of heart disease and other health problems.

In the fight against Big Soda, health advocates are drawing lessons from years of battles against Big Tobacco that included education campaigns to discourage kids from taking up smoking, restrictions on marketing tobacco products and bans on smoking in public places.

"If cigarette warnings are a precedent, we know they help reduce usage," Marion Nestle, the author of "Food Politics" and a professor at New York University, said in an email, referring to warnings on sugar-sweetened beverages. The adult smoking rate in the U.S. fell from 42.4 percent in 1965 to 19 percent in 2011, according to the CDC, amid sustained anti-smoking campaigns that included warning labels on cigarettes about the dangers of smoking.

In June, San Francisco became the first city to approve warning labels on sugary drinks, like teas, sodas and sports drinks, that said, "WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay." The warnings have yet to take effect, however, after the American Beverage Association, which lists Coca-Cola and Red Bull North America among its members, sued the city, citing free speech violations.

The litigation against San Francisco has not stopped Baltimore from pursuing a similar path. Baltimore Councilman Nick Mosby introduced legislation Monday that would require businesses, advertisements and restaurant menus to post a message from the Baltimore City Health Department: “WARNING: DRINKING BEVERAGES WITH ADDED SUGAR CONTRIBUTES TO TOOTH DECAY, OBESITY, AND DIABETES.”

In fact, San Francisco's ordinance was part of what inspired Baltimore's proposal, said Leana Wen, the city's public health commissioner. Another factor was concern coming from the city's own residents.

"We’d been hearing from our community that there is increasing concern about the number of children who are overweight or obese," Wen said. "The warning label we see as being critical because we see and hear so many of our parents saying that they would make a different choice if they knew it was unhealthy," she said.

The beverage industry has fiercely opposed measures meant to discourage people from buying sugary drinks. From 2009 to 2015, the soda industry spent at least $106 million on lobbying efforts to defeat proposals for taxes on sugary drinks and sodas in Chicago, San Francisco and other cities and states, although it failed to prevent the passage of such a tax in Berkeley, California, an analysis by the Center for Science in the Public Interest found.

With warning labels, the industry's stance is hardly different. “Consumers want factual information to help make informed choices that are right for them, and America’s beverage companies already provide clear calorie labels on the front of our products," said Lauren Kane, senior communications director for the American Beverage Association, in response to a request for comment on Baltimore’s proposal. "A warning label that suggests beverages are a unique driver of complex conditions such as diabetes and obesity is inaccurate and misleading," Kane said.

Others are careful to point out that as a tactic to deter people from buying sodas, sweetened ice teas and sports drinks like Gatorade, warning labels are in their infancy, and other measures would be necessary to encourage people to eat, drink and live healthier.

"Since no warning labels are as yet in use, we have no information about efficacy," Nestle said. But, she said, "if nothing else, they should raise awareness and that alone is a good thing."

Baltimore, meanwhile, is exploring options besides labeling to encourage people to eat and drink healthier, such as free grocery delivery to areas defined as food deserts or requirements that vending machines carry more, healthier options, Wen, the public health commissioner, who is a doctor, said. She recalled treating patients with health conditions that shocked her — a teenager with Type 2 diabetes, which is also referred to as adult-onset diabetes, or a 8-year-old weighing 200 pounds — and yet were reaching epidemic proportions.

"If we had an epidemic killing our children like measles or Ebola, we’d certainly be putting all hands on deck," she said. "We cannot wait until more of our children become ill and die."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.