Xi Jinping White House Visit: South China Sea Dispute Will Be Central To Talks With Obama

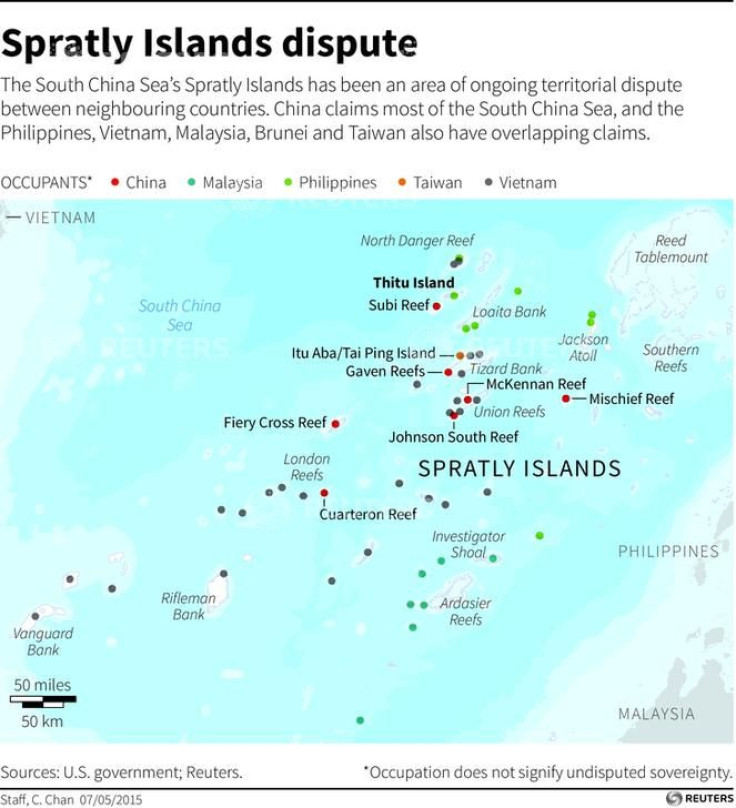

What was once a group of obscure, almost entirely submerged rocks and reefs on the fringes of the Spratly Island group in the South China Sea are now set to become a major point of contention in the upcoming state visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to the White House Thursday evening.

Over the last three years China has developed seven so-called artificial land masses in the South China Sea by dumping sand onto reefs and shoals and then adding expansive military bases on top, which the U.S. and China’s regional rivals contend is against the United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Sea, an affront to to freedom of navigation and a blatant attempt to snatch full sovereignty over the regions' precious assets. What Obama will do about this is yet to be seen, but international experts claim that Xi will not budge over his country’s claim to the region, raising questions about how the U.S. will attempt to appear strong to its Asian allies while trying to not anger an increasingly powerful China.

“Unfortunately, the president has a very weak hand on this issue because apparently the White House chose not to cross the international waters around these islands that China is illegally claiming,” said Dean Cheng, senior research fellow at the Asian Studies Center at the Heritage Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based conservative think tank. “U.S. Pacific Command wanted to do this and the White House said no. So we have essentially taught the Chinese to ignore any of our protests over the islands because we have nothing to back it up with.”

CHINA'S ARTIFICIAL ISLANDS

The Spratly Island chain is a region of over 30,000 islands, shoals and reefs, many of which are nearly 1,000 miles from China’s shores. Despite only laying claim to the leftovers areas that Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam didn't want when they began claiming portions of the islands more than fifty years ago, China has no interest in chasing away its rivals and stealing the islands for itself, said Cheng. However, it is aggressively attempting to claim the region’s airspace, rich fishing grounds and the seabed, where it believes vast reserves of oil and gas exist.

For China to achieve that goal, it began developing a main military island known as Fiery Cross, which has quickly grown into a sprawling landmass over 200 hectares in size, around 2,000,000 million sq. meters. Since construction began in 2014, Fiery Cross now has an airstrip in excess of 3,000 meters, which is big enough to land most of China’s jet fighters and transport aircraft. The harbor area is wide enough to accommodate the largest ships in the country’s navy, while waters around the island are deep enough that China’s increasingly advanced submarines can lurk undetected. It then created six more islands.

Despite only legally claiming the islands that it has created, China is claiming as much as 80 percent of the entire South China Sea, which is around 1.3 million sq. miles in total.

Under normal U.N. maritime law, China is entitled to territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles from the coast of any lands that it owns, meaning no one can enter without permission. It would also be entitled to what's known as the exclusive economic zone, an area 200 miles from its coast where it can drill for oil or gas, but where the waterways are still open for anyone to transit. However, those rights only exist for geographical features that are above the surface of the water.

“If you dump sand on top of a submerged reef and turn it into an artificial island all you get is a 500 meter safety zone, which is what you get around an oil rig or any other artificial floating structure,” said Greg Polling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C.,-based policy think tank. “In some of these cases there is no legal maritime entitlement created by these features, which means the U.S. or anybody else would be in international waters and can enter within 12 nautical miles of China’s artificial islands.”

AMERICA’S CHINA PROBLEM

While the U.S. has largely stayed out of issues involving the Spratly Islands, it has a number of main issues with what China has been doing in the South China Sea, according to Polling.

“The U.S. wants to ensure disputes between China and its neighbors are resolved peacefully, and that peace in the Pacific is preserved and China doesn’t bully neighbors,” said Polling. “It also wants to preserve the rights of navigation so that the U.S. and others can freely pass through the waters without being harassed by Chinese ships or planes.”

But what’s more important than preventing China from bullying it rivals into submission, said Polling, is stopping Beijing from creating a dangerous precedent. If China is able to get away with claiming large swathes of sea and seabed, then what’s stopping Russia from claiming the Arctic seabed, or Iran from claiming parts of the Persian Gulf? In this respect, the U.S. has an interest in preserving international law. The only problem for the U.S., and no doubt China will make a point of this when Xi sits down with Obama, is that it is not even a signatory to the U.N. maritime laws.

U.S. SOLUTIONS

While Obama will likely discuss the South China Sea with Xi at the state dinner, diplomatic efforts aimed at getting China to stop building its artificial islands and allow freedom of navigation have so far been fruitless, according to Cheng. The available options open to the U.S. include the White House authorizing the Navy and Air Force to conduct flights over the artificial islands to test China's resolve, which would be in line with comments made by Defense Secretary Ash Carter in May when he said that the U.S. military “will fly, sail, and operate wherever international law allows.”

But since those comments, the U.S. has done nothing. Arizona Sen. John McCain has said the White House's reluctance in sending navy ships into the region has been a "dangerous mistake that grants de facto recognition of China's man-made sovereignty claims." McCain made the remarks last week at a Senate Armed Services committee hearing held ahead of the Chinese president's visit, adding that the U.S. must assert its rights of navigation forcefully.

However, Obama has so far prevented his navy Pacific Command from doing that, fearing igniting a conflict in the region, according to Cheng, who said that few other options exist other than probing the waters.

“After the Xi-Obama summit the administration could move for a full court press against China. It could authorize flights and ships to go within 12 miles, it might impose sanctions on cyber violations and press the Chinese on international property rights,” said Cheng. “But we have little evidence that the Obama administration is willing to undertake the consistent, persistence and resolute action before he leaves office in 2017.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.