As Zika Virus Spreads, Gaps In Diagnostic Testing Present Opportunities For Drug Companies

Most of the world had not yet heard of the Zika virus in November, when Sudhir Bhatia, the CEO of German biotechnology company Genekam, received a request from a customer in Mexico. Could Genekam start developing a diagnostic test for the virus? Because Zika was going to become a problem, Bhatia recalled the customer saying. Genekam got to work.

One of the most vital but perhaps overlooked tools necessary to confront an outbreak like the Zika virus is a reliable, accurate and easily accessible diagnostic test. The lack of one has proved a major hurdle for researchers and governments trying to understand the disease and accurately assess the threat it poses to public health, as the number of cases rises and the potential implications of the virus take hold. But now, sensing opportunity, more drug and diagnostics companies are developing, or considering developing, simpler and more reliable tests that can determine whether a person has been infected with the Zika virus.

“Since May, you’ve had diagnostics manufacturers watching what’s been happening in Brazil,” said Kelly Wroblewski, director of infectious diseases for the Association of Public Health Laboratories, based in Maryland. But the past month has seen that change dramatically, as the outbreak garners more and more attention. Now, “manufacturers have been really testing the waters in a more thoughtful way,” Wroblewski said.

At least three or four of APHL’s corporate members are considering developing diagnostics for the Zika virus. Wroblewski declined to name which ones but described them as “bigger diagnostics manufacturers.” They have called APHL in an effort to gauge the market, asking if testing will expand beyond its current turf, in public health laboratories, to clinics and patients themselves.

“It’s a good environment for generating the incentive needed to invest in diagnostics,” Josh Michaud, an associate director on the global health policy team at the Kaiser Family Foundation, said of the Zika virus outbreak. “You have global attention focused on this. You have what appears to be rapid spread of the virus” across both middle and high-income countries across the Americas, he pointed out. “That is a recipe for greater investments — and probably return on investments for research — into diagnostics.”

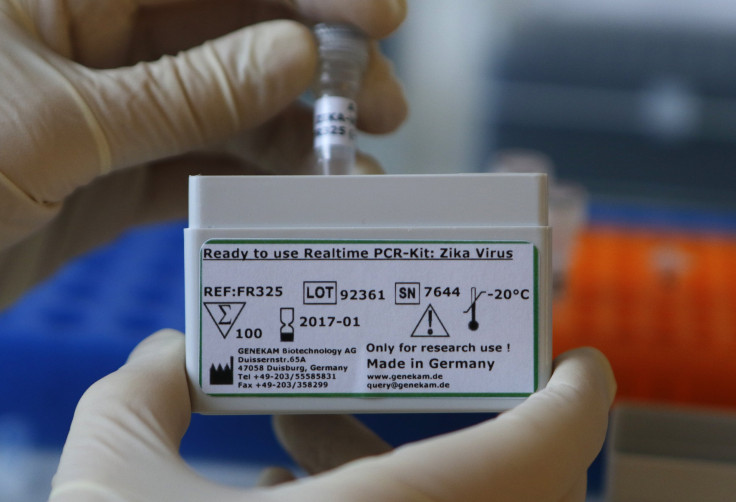

Genekam announced Jan. 27 that it had developed a “highly sensitive” DNA test to detect the virus. It stated in a press release that the price per test would range from five to seven euros, and the cost of a full kit, which according to company literature contains 100 tests, is 699 euros ($777). In order to use the kit, labs need a machine known as a real-time PCR thermocycler, plus a centrifuge and other items like microtubes and pipettes, but it produces results within two and a half hours, Bhatia, the Genekam CEO, said in a phone interview.

For Genekam to work on a diagnostic test for Zika was a logical decision, Bhatia said. One of the areas of the biotech company’s slim focus is diagnostics tests specifically for mosquito-borne diseases; for 12 years the company has worked on tests and therapies for flaviviruses, the family that includes Zika.

Diagnostic tests for the Zika virus are not commercially available, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says on its website. In the U.S., if a doctor wants to test a patient for the disease, a sample, usually blood, has to be sent to the CDC’s Arbovirus Diagnostic Laboratory or to a select number of state laboratories for testing. Even then, the process is unwieldy. The CDC’s protocol for diagnosis amounts to deploying a seeming patchwork of chemical tests and tools, at least as laid out in a CDC memorandum dated Jan. 13.

A proper diagnostics kit, on the other hand — the kind that more manufacturers now want to build — would contain everything from chemical reagents to step-by-step instructions in a single box. The exact financial rewards of creating and distributing such a kit aren’t fully clear, but if previous pandemics are any indication, diagnostics, vaccines and other medicines related to the disease of the year may be well worth investing in.

In response to the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa in 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama requested $6.2 billion in emergency funding that included $157 million toward manufacturing and testing vaccines and therapeutics. And after the global swine flu pandemic of 2009, Novartis, the Swiss drugmaker, reported that its H1N1 vaccine added $1.1 billion in profits just in the first quarter of 2010.

For several years, the Zika virus has been on the radar of InBios International, a medical diagnostic company in Seattle working on developing diagnostics tests. The company’s focus is infectious diseases, and among its diagnostic products are immunoassays for testing and diagnosing viruses similar to Zika, like mosquito-borne dengue and West Nile. But it was the current outbreak that helped render Zika a priority.

“We have people sending emails every day looking for the kit,” Wendy Bagnato, InBios’ senior marketing and sales manager, said, referring to a diagnostics test. Public health laboratories from South America to India have asked about tests, she added. Bagnato declined to disclose the price of a test, but she said the company generally tried to manufacture tests and “not sell them at too high a price.”

Bruce Carlson, publisher of Kalorama Information, the healthcare market research division of MarketResearch.com, estimated that the market for Zika diagnostic tests could be worth “tens to hundreds of millions” in the next few years.

Researchers and public health experts also see these tests as extremely valuable. They say better diagnostics are absolutely crucial to combating the virus, for several reasons.

Four out of 5 people who contract the virus never show symptoms, a phenomenon that reduces their odds of being tested while the virus is active. If patients are tested after it subsides, the only way to detect a past infection is with a test that measures antibodies, proteins that are remnants of the immune system’s fight against the disease.

The problem with existing antibody tests is that they often fail to distinguish between Zika and similar viruses related to it and to which people living in Central and South America are frequently exposed, said Scott Weaver, director of the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

“Good surveillance depends on good diagnostics,” Weaver said. When diagnostic tests instead produce false positives, or unreliable results, they risk jeopardizing efforts to understand and combat the disease.

“Without good diagnostics, you won’t be able to do the studies, create the data and make the link based on good evidence between the infection and the birth outcomes,” Michaud, of the Kaiser Family Foundation, said, referring to the suspected but unproven link between the Zika virus and the birth defect microcephaly, which leads to developmental delays.

Researchers also suspect a connection between Zika and Guillain-Barré syndrome, a neurological disorder, but they don’t know for sure, because the inability to confirm cases of Zika has hindered efforts to conclusively link the virus to its alleged effects, Michaud pointed out. He added, “Right now,we are in a fog of conjecture about the extent of Zika infection and its link to the supposed severe birth defects that everyone is so worried about.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.