30 Years After Berlin Wall Fell, Stasi Archive Move Sparks Controversy

Almost 30 years after the Berlin Wall fell, Germany's parliament voted Thursday to transfer the vast secret police files of the former East German communist regime into the Federal Archives -- despite concerns voiced by some historians and ex-dissidents.

One of those opposed to the move, former regime critic Werner Schulz, now a Greens party member of the European Parliament, charged that it was "premature" and voiced fears that "a lid will be put on history".

And the historian Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk, another former dissident, told news weekly Der Spiegel it "now seems like a line is being drawn" under efforts to come to terms with the former dictatorship.

During the Cold War, East Germany's feared and hated "Staatssicherheit" or Stasi police built a repressive apparatus of surveillance and intimidation, using millions of officers and informants, bugging technology and secret prisons.

In the chaos of 1989-90, as the Soviet-allied police state collapsed, Stasi officers frantically shredded files and, when the machines broke down under the strain, tore documents up by hand to pulp or burn the scraps.

However, "citizen committees" stormed Stasi offices -- including its East Berlin headquarters, on January 15, 1990 -- and seized millions of files and torn-up documents to preserve them for the future.

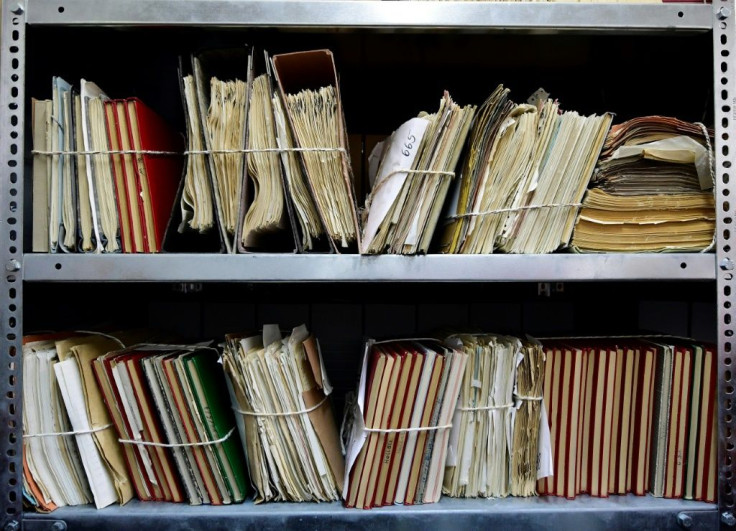

After reunification in 1990, a Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records was swiftly appointed to safeguard the hoard -- an astonishing 111 kilometres (69 miles) of paper files, more than 15,000 bags of paper shreds, over 1.7 million photographs and thousands of audio and video recordings.

In the three decades since, more than three million people have requested to view files, most of them victims wanting to know what the state knew about them and -- often more painfully -- what their former co-workers, teachers or even family members had reported about them.

'Fit for the future'

After Thursday's parliamentary vote, the archives, much of the paper now yellowing, will from mid-2021 come under the guardianship of the Federal Archive.

Roland Jahn, the current federal commissioner, pledged that the files will remain accessible to victims, journalists and historians, and that the papers will benefit from expertise and infrastructure for preserving and digitising documents.

Jahn, also a former civil rights activist, said the aim was to make the Stasi archives "fit for the future as we can tap the expertise, technology and resources under the roof of the Federal Archives".

However, some critics voiced fears the Stasi papers will be swallowed up in the far bigger archive.

Historian Hubertus Knabe, who formerly ran the memorial at a former Stasi prison in Berlin's Hohenschoenhausen district, warned that "the largest institution for dealing with the GDR (German Democratic Republic) past will no longer exist after 2021".

A support group for former Stasi victims, the Aufarbeitungsverein Buergerkomitee 15. Januar, cautioned that the independent status of the commissioner and the archives must never be compromised.

"There are fears that information on oversight as well as the viewing of the files" could be subject to political whims, and embarrassing information could be kept under wraps, it argued.

Jahn, asked if the restructuring was the wrong move on a key anniversary, told public broadcaster Deutschlandfunk: "Quite the opposite."

"We are sending the message that on the 30th anniversary... we have this symbol of the peaceful revolution -- that is, the access to the files and the possibility to use them -- and that is something that we are securing permanently."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.