50-Million-Year-Old 'Collision That Changed The World' Altered Conditions For Life On Earth

Scientists have discovered that a massive tectonic shift that saw entire continents crash into each other 50 million years ago drastically transformed the conditions for life on Earth. Scientists at the Princeton University discovered that the "collision that changed the world" increased the oxygen levels in Earth's oceans, which in turn, altered the conditions for life.

Emma Kast, the lead author of the study and a graduate student of geosciences at Princeton, created an exhaustive record of the ocean nitrogen levels using microscopic seashells. The records span a period of time between 70 million years ago -- a little before dinosaurs were wiped out from the face of the earth -- and 30 million years ago.

“These results are different from anything people have previously seen,” Kast said in a statement. “The magnitude of the reconstructed change took us by surprise.”

"In our field, there are records that you look at as fundamental, that need to be explained by any sort of hypothesis that wants to make biogeochemical connections," said John Higgins, a co-author or the research paper and an associate professor of geosciences at Princeton. "Those are few and far between, in part because it's very hard to create records that go far back in time. Fifty-million-year-old rocks don't willingly give up their secrets. I would certainly consider Emma's record to be one of those fundamental records. From now on, people who want to engage with how the Earth has changed over the last 70 million years will have to engage with Emma's data."

According to the scientists, 78 percent of the earth's atmosphere is made up of nitrogen. The gas is also the primary substance for all life on the planet. While all organisms on earth require a fixed level of nitrogen to survive, some are able to "fix" it by converting the gas into biologically useful forms. The gas has two stable isotopes -- 15N and 14N. The ratio of these isotopes in oceans can help determine the level of oxygen in the ocean.

Tiny organisms in the ocean called foraminifera incorporate the ratio of nitrogen isotopes, which in turn, is preserved onto their shells when they die. The scientists studied the fossils of these creatures to figure out the 5N-to-14N ratio of earth's ancient oceans. This allowed the researchers to calculate the changes in oxygen levels.

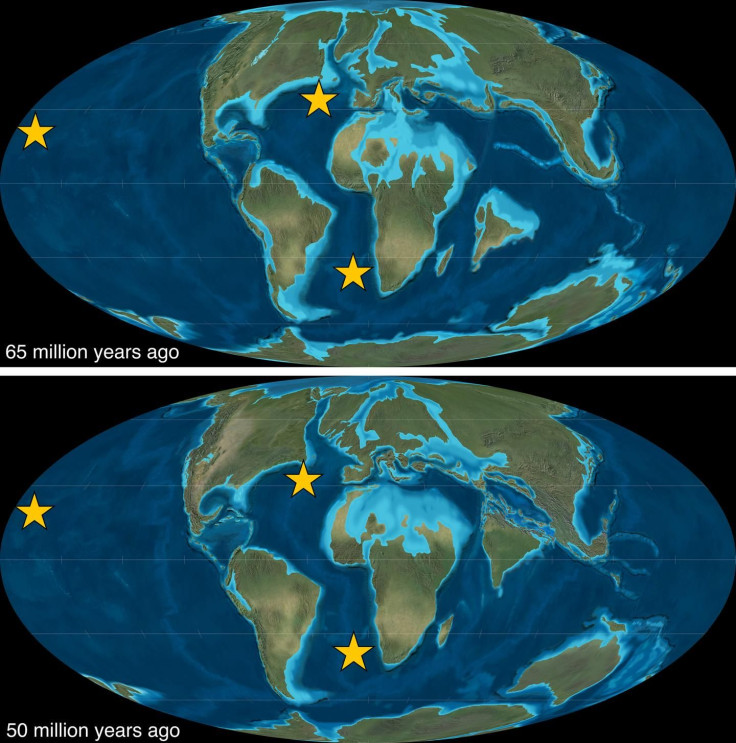

“Contrary to our first expectations, global climate was not the primary cause of this change in ocean oxygen and nitrogen cycling,” Kast said. The researchers believe that the tectonic shift that led to the collision of India with Asia, which was named the "collision that changed the world" by famed geoscientist Wally Broecker, killed a prehistoric sea known as the Tethys.

“Over millions of years, tectonic changes have the potential to have massive effects on ocean circulation,” said Daniel Sigman, the senior author of the study. “On timescales of years to millenia, climate has the upper hand.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.