This 5,000-Year-Old Hunter-Gatherer Had The Earliest Known Plague Strain: Study

KEY POINTS

- This pushes back the bacteria's first appearance 2,000 years earlier than suggested

- The early strain was likely less transmissible and less aggressive

- It challenges suggestions that the bacteria evolved mostly in megacities

The Black Death wiped out nearly half of Europe's population in the 1300s. But how far back did the bacteria affect humans? A team of researchers may have possibly found the oldest strain of it in a 5,000-year-old specimen.

The plague bacteria was discovered in the skull of a 20- to 30-year-old hunter-gatherer (RV 2039) from 5,000 years ago, Cell Press said in a news release. This particular specimen was excavated along with another person's remains at a region called Rinnukalns in present-day Latvia in the 1800s. However, it got lost until it was recovered in a German anthropologist's collection in 2011.

For their study, published in the journal Cell Reports Tuesday, the researchers analyzed teeth and bone samples from four hunter-gatherers, including RV 2039, and tested them for viral and bacterial pathogens.

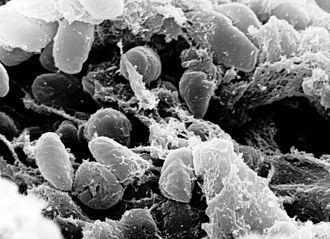

Surprisingly, they found traces of Yersinia pestis, the bacteria behind the Black Death, in RV 2039. Further analysis revealed that the strain in RV 2039 was, indeed, the "oldest strain ever discovered." It was likely a part of the lineage that came bout 7,000 years ago, just a few hundred years after Y. pestis separated from its predecessor, Cell Press noted.

The earliest known strain of Yersinia pestis--better known as the bacteria that caused the #Plague (or Black Death)-- has been found in the remains of a 5,000-year-old hunter-gatherer. Learn more about this surprising find in @CellReports https://t.co/VVSy6gCA8z pic.twitter.com/oGo8er97Ng

— Cell Press (@CellPressNews) June 29, 2021

"What's most astonishing is that we can push back the appearance of Y. pestis 2,000 years farther than previously published studies suggested," study senior author, Ben Krause-Kyora of the University of Kiel in Germany, said in the Cell Press news release. "It seems that we are really close to the origin of the bacteria."

Not as contagious as the Black Death

Although the extent to which RV 2039 was affected by the virus is unclear, the researchers said that it was likely less aggressive and less transmissible than the modern strains. The strain in RV 2039 had an almost complete Y. pestis genetic set, Krause-Kyora noted, but it was missing the particular gene that lets it be transmissible through fleas. It's also the gene responsible for being effectively transmissible to human hosts.

According to the researchers, it would still take over a thousand years after RV 2039 for Y. pestis to develop "flea-based" transmission. As such, it's likely that RV 2039 was infected through the bite of a rodent, possibly a beaver as it's the most frequently recorded species at the site. It is also a common carrier of the Y. pseudotuberculosis, which "directly precedes" the Y. pestis strain.

"However, this does not mean that these strains were harmless," the researchers wrote. "Given their presence in the blood of the infected, they could still have been potentially deadly for the individual."

This picture of a "slow-moving," less transmissible disease contradicts previous hypotheses about Y. pestis.

"Our data do not support the scenario of a prehistoric pneumonic plague pandemic, as suggested previously for the Neolithic decline," the researchers wrote.

It also challenges suggestions that Y. pestis evolved mostly in megacities when this time frame puts RV 2039's infection long before large cities were formed.

According to BBC News, although other researchers have been receptive to the new study, they don't dismiss the possibility that the disease was also widely spreading in Europe at the time.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.