9/11’s New Victims: Cancer And Other Diseases Linked To Terrorist Attack Claim More Lives

When Placido Perez closes his eyes, he can still see the World Trade Center towers beneath him. On weekends, he would sometimes fly his red-and-white Cessna along the Hudson River, taking selfies with the towers in the background, stark against a cerulean sky. “I still look at the pictures all the time,” he says. “I remember the good times. It’s what gets you through.”

Perez also has pictures he took of the September 11, 2001, attacks. He was standing at the base of the towers that morning with a digital camera, not far from where he worked as a manager at a telecommunications company. “I was on my way to work, and, boom, I heard a turbine smash into one of the buildings,” he says. “I remember the sounds and the people jumping [from the towers]. That marble plaza outside of the towers where the globe sculpture was—remember it had speakers? Muzak was playing. They couldn’t stop the music. It was automatic. People were jumping, and debris was flying. It was awful.”

Perez, a licensed emergency medical technician, stayed downtown to help people trying to escape the burning buildings. The next day, he returned to the site and volunteered alongside thousands of police officers, firefighters, construction workers and others to search for survivors. He didn’t leave Ground Zero for a week, working 12- to 14-hour shifts. When he needed rest, he slept at the site.

Now, on the 15th anniversary of 9/11, he’s struggling to accept a harrowing truth: His time saving lives at Ground Zero has made him sick—and could kill him. “Between 2005 and 2009, I ended up in the emergency room six or seven times, thinking I was having a heart attack and about to die,” says Perez, 59. They were panic attacks—his heart rate as high as 157 beats per minute, well above the average for a healthy man his age. Then came the respiratory problems that would choke him in his sleep and wake him in the night. He discovered he had restrictive lung disease, post-traumatic stress, rhinitis, asthma and swelling of the liver so severe it began to interfere with his blood platelets, esophagus, diaphragm, stomach and other digestive organs.

He says his liver disease is now so far advanced and the scarring so great that it cannot heal or regenerate—only a transplant can help him. All he can do is wait. Perez says if the disease progresses further, the doctors fear it will mean cancer or liver failure. “I have never done any drugs, and I don’t drink. I weigh 163 pounds and am thin, except for my liver, which is like an inner tube around my waist.

“This shouldn’t be happening to me.”

Ground Zero Exposure

Perez is one of the thousands fighting deadly diseases as a result of exposure to Ground Zero. Doctors with the World Trade Center Health Program, which the federal government created in the aftermath of the attacks, have linked nearly 70 types of cancer to Ground Zero. Many people have fallen victim to cancers their doctors say are rare, aggressive and particularly hard to treat. “The diseases stemming from the World Trade Center attacks include almost all lung diseases, almost all cancers—such as issues of the upper airways, gastroesophageal acid reflux disease, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, panic and adjustment disorders,” says Dr. David Prezant, co-director for the Fire Department of the City of New York’s World Trade Center Medical Monitoring Program.

With the exception of the Civil War battle of Antietam, more American lives were lost on September 11, 2001, than on any other day in U.S. history: 2,996 people were killed—265 on the four hijacked planes, 125 at the Pentagon and 2,606 at the World Trade Center and surrounding area. More than 411 emergency workers died on 9/11, and the total number of rescue and recovery workers who have died has more than doubled since the attacks, to 1,064 as of July, according to data obtained exclusively by Newsweek from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

The wider population is also suffering: As many as 400,000 people are estimated to be affected by diseases, such as cancers, and mental illnesses linked to September 11. This figure includes those who lived and worked within a mile and a half of Ground Zero in Manhattan and Brooklyn, the vast majority of whom still don’t know they’re at risk. Mark Farfel, director of the World Trade Center Health Registry, which tracks the health of more than 71,000 rescue workers and survivors, says, “Many people don’t connect the symptoms they have today to September 11.”

Richard Dixon, a Bronx-based cop with the New York Police Department, agrees. “You don’t think that the cough you get today will be the cancer you get tomorrow.” He spent two months working in rescue and recovery at Ground Zero. Since then, he’s had sleep apnea, sinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which can be a precursor to cancer.

And he’s one of the lucky ones. Unlike others on the force, he’s still able to work—and is cancer-free. “We lost 23 NYPD officers in the attacks,” he says. “But many more have died since then of these September 11–related illnesses. We need to find out why, or that list of names on the 9/11 memorial is going to just keep growing.”

The World Trade Center Cough

Days after the attacks, rescue workers started showing up at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York for treatment and medical assistance. Many of them had injuries and respiratory problems from the debris that had fallen on them, including what became known as “the World Trade Center cough.”

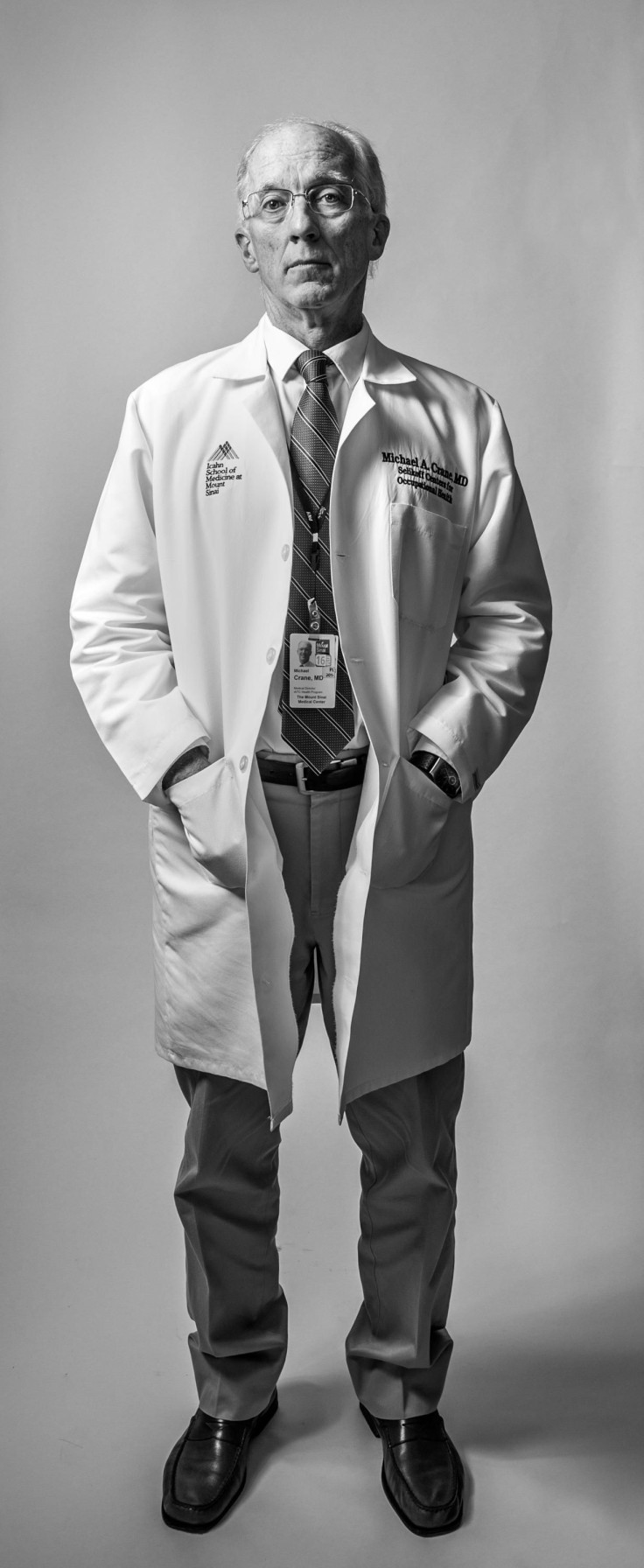

“The symptoms these patients have are terrifying,” says Dr. Michael Crane, director of the World Trade Center Health Program’s lead clinical center at Mount Sinai, which treats around 22,000 rescue and recovery workers. “They will suddenly wake up and find they cannot breathe.”

One Mount Sinai patient who had the cough was John Soltes, a retired cop for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which had oversight of the World Trade Center towers. He worked at Ground Zero for almost nine months clearing debris and recovering the remains of his colleagues. “I only had the cough for a year,” he says. “I know some guys who still have it.” His cough led to GERD and a serious complication of that condition, called Barrett’s esophagus, which can develop into cancer. “I’ve already dealt with skin cancer on my face, my cheek and my back,” which are also 9/11-related, he says. “So I am trying to be careful.”

Daisy Bonilla, an NYPD school safety agent, also worked in rescue and recovery at Ground Zero, taking care of orphaned children whose parents died in the attacks. Today, her upper airways are too inflamed to swallow solid food. “Food would get stuck in my esophagus, and I would feel like I was choking,” she says. “So now I have protein shakes or have to have all my food pureed. I haven’t been able to go to a restaurant with friends. I haven’t had solid foods or eaten a steak in over a year. It sucks, but I am getting used to it. I try to look at it in a positive way—at least I am alive.”

Crane is also regularly seeing cancers that have been developing since as far back as 2005. As of June, 5,441 of the 75,000 people enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Program have been diagnosed with at least one case of 9/11-related cancer, according to data Newsweekobtained from the program. And many of them have multiple cancers, with the total number of cancers certified at 6,378 as of June. “Any internal cancer below the skin is awful,” Crane says. “But cancers of the digestive organs, cancers in the gut, can sit there sometimes, and you don’t even know they are growing.”

Paul Gerasimczyk, a retired NYPD cop who worked in the Ground Zero cleanup, says he first went to Mount Sinai in 2005 for treatment for “the cough” and discovered he had asthma. “Beads of sweat were breaking out on my face, I was coughing so hard,” he says. “The doctor said, ‘Did you call the ambulance and go to the hospital?’ I said, ‘No, I thought it was just coughing.’ And she said, ‘You had an asthma attack.’” By 2007, Gerasimczyk learned he had developed kidney cancer, as well as GERD. “When you’re told you have cancer, you’re in disbelief,” he says. “You feel you’re healthy, and you’re in denial. You feel you can beat it, the operation will be successful.”

He says two close friends who worked at Ground Zero didn’t make it—one died of pancreatic cancer and the other of brain cancer. “They don’t just die; they die in the worst ways imaginable,” he says. “My friend Angelo Peluso, who died in 2006, they had to remove an egg-shaped tumor from his brain. The first time they operated on him, he was mentally impaired and could only say my name. The second time they operated, he never left the hospital, and in months he was gone. It just rips the heart out of your chest.”

A Cesspool of Cancer

Today, 15 years after the attacks, doctors are starting to understand why people are still dying. When the towers came down, they say, they released a massive plume of carcinogens, turning lower Manhattan into a cesspool of cancer and deadly disease. “We will never know the composition of that cloud, because the wind carried it away, but people were breathing and eating it,” says Mount Sinai’s Crane. “What we do know is that it had all kinds of god-awful things in it. Burning jet fuel. Plastics, metal, fiberglass, asbestos. It was thick, terrible stuff. A witch’s brew.”

In a report issued just months after the attacks, the National Resources Defense Council, a New York–based environmental advocacy group, noted that the World Trade Center’s north tower contained as much as 400 tons of asbestos. That, along with burning office furniture, mainframe computers and the thousands of fluorescent lights in the buildings, led to the release of lead, mercury, volatile organic compounds and other deadly poisons. “An environmental emergency such as this, with hundreds, if not thousands, of toxic components simultaneously discharged into the air on the scale of September 11th is unprecedented,” the organization wrote, and the effects “unknown.”

Because the fires burned at Ground Zero for more than 90 days, a later study explained that the contaminants found in the dust immediately after the attacks continued to show up in samples for weeks. The results supported “the need to have the interior of residences, buildings, and their respective HVAC [heating, ventilation and air-conditioning] systems professionally cleaned to reduce long-term residential risks before rehabilitation,” the study said, noting the probability of “acute or long-term health effects” from dust, which could be stirred up endlessly.

New research confirms that this toxic cocktail caused heightened rates of cancer. “If you compare our cancer rates to the general U.S. population, our rates are about 10 percent higher than expected,” says the Fire Department’s Prezant, who tracks the health profiles of 15,700 firefighters and emergency medical services workers. “If you compare it to our pre–September 11 data, the cancer rates range from 19 to 30 percent higher for our firefighters.” He says the data are carefully adjusted for age, exposure and other factors to “yield the most conservative numbers.”

Prezant also found that firefighters at Ground Zero had a substantial reduction in lung capacity. “Normally with lung exposure, you recover,” he says. “I found that their lung function did not recover, despite treatment and despite time. I attribute it to the extremely inflammatory nature of the dust found at the World Trade Center site. When you look at [the dust particles] under a microscope, they are very jagged, and they are coated with carcinogens.”

Yet following the attacks, the government repeatedly announced the air within Ground Zero’s 16-acre zone was safe to breathe. One week after the towers fell, Christine Todd Whitman, then the head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, stated that the air did “not pose a health hazard.” She was wrong. At the time, the EPA “did not have sufficient data and analyses to make such a blanket statement,” according to a 2003 U.S. inspector general report. “The White House Council on Environmental Quality [under George W. Bush] influenced, through the collaboration process, the information that the EPA communicated to the public through its early press releases when it convinced the EPA to add reassuring statements and delete cautionary ones.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals later ruled that Whitman wasn’t liable for the EPA’s claims, because she did not intend any harm. Perez, the rescue worker, is still bitter about the EPA’s assurances. He lost several friends to breathing the dust. “No one was saying anything about the chemicals and what it meant to be breathing the ash of so many toxins mixed with human remains,” he says. “I had friends that developed carcinoma in their lungs, and many of them were deep in the pile.”

Too Young to Die

Since 9/11, many of those who were at Ground Zero have dispersed to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and more than 15 countries, including Canada and the U.K., as well as parts of continental Europe and the Middle East, says Farfel, the World Trade Center Health Registry director. “You see all these survivors with elevated asthma, behavioral issues, post-traumatic stress, substance-abuse issues and increased cancer rates,” he tells Newsweek. “This has now been linked to the attacks and corroborated by multiple studies.”

The registry is part of a broad network of post–September 11 clinics and organizations belonging to the World Trade Center Health Program. The program is publicly funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the CDC, and it consists of a responder program for rescue and recovery workers like Perez, as well as a thinly attended survivor program for those who lived and worked near Ground Zero. “A lot of people who should enroll in the program don’t, because they think other people need it more than they do,” Crane says.

No one knows exactly when downtown New York became safe again—and some, like Bonilla, say it isn’t safe now. But those directly exposed to the World Trade Center disaster who can prove they lived or worked in the area between September 11, 2001, and July 31, 2002, when the cleanup ended, can receive free treatment for a growing list of illnesses linked to the 9/11 attacks. In December, Congress reauthorized a bill to provide free medical services and treatment to responders and survivors of September 11 for the rest of their lives. In fiscal 2016, Congress will spend $330 million on the program. That number will gradually rise to $570 million by 2025.

Despite these substantial resources, Farfel says, it remains difficult to get people to link an illness they may be suffering from today to attacks 15 years ago. Farfel has a staff of a few dozen people based in Long Island City, New York, trying to alert people to the dangers of their exposure to the World Trade Center site and how to get free treatment. They even have Chinese and Spanish speakers reaching out to more underserved groups. “It’s a real challenge for us,” he says. “How do you make contact with and encourage people to apply, especially those who may already be suffering and are isolated?”

Farfel’s goal is to limit the number of people who continue to die from 9/11-related illnesses. As of July 2016, 1,140 people have died since the attacks, the majority of whom worked or lived at or near the site, according to data from the World Trade Center Health Program. But that’s only based on unsolicited reports, since the program does not seek out mortality data, nor analyze it for things like cause of death. The program says it is focused solely on health monitoring and treatment.

The number of fatalities is likely to be far greater than that tally. Fewer than 10,000 people deemed eligible for the survivor program have enrolled. That means nearly half a million people exposed to what doctors are now calling “the World Trade Center disaster area” remain untreated and unaccounted for. The amount of care this population will need over the next decade is expected to be monumental, as doctors note the incubation periods for cancer can be up to 15 to 20 years—a time window patients are hitting now. “While this population is getting older,” says Crane, “it’s still relatively young to be looking at death.”

The average age of rescue and recovery workers is approaching 54, says Andy Todd, co-deputy director of Mount Sinai’s World Trade Center Health Program. More than 86 percent of them are men, and more than half are suffering from multiple World Trade Center–related illnesses. Fewer than 10 percent have cancer right now, Todd says, but as these people get older, both he and Crane expect that number to steadily rise. “If you were down there, and especially if you were a responder,” Crane says, “you need to be seen.”

‘They Found Some Bones’

This time of year is always hardest for the 9/11 survivors, Perez says, because they are plagued by disturbing thoughts and memories. Aside from cancer and other diseases, doctors say, many suffer from the same mental health problems as soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.

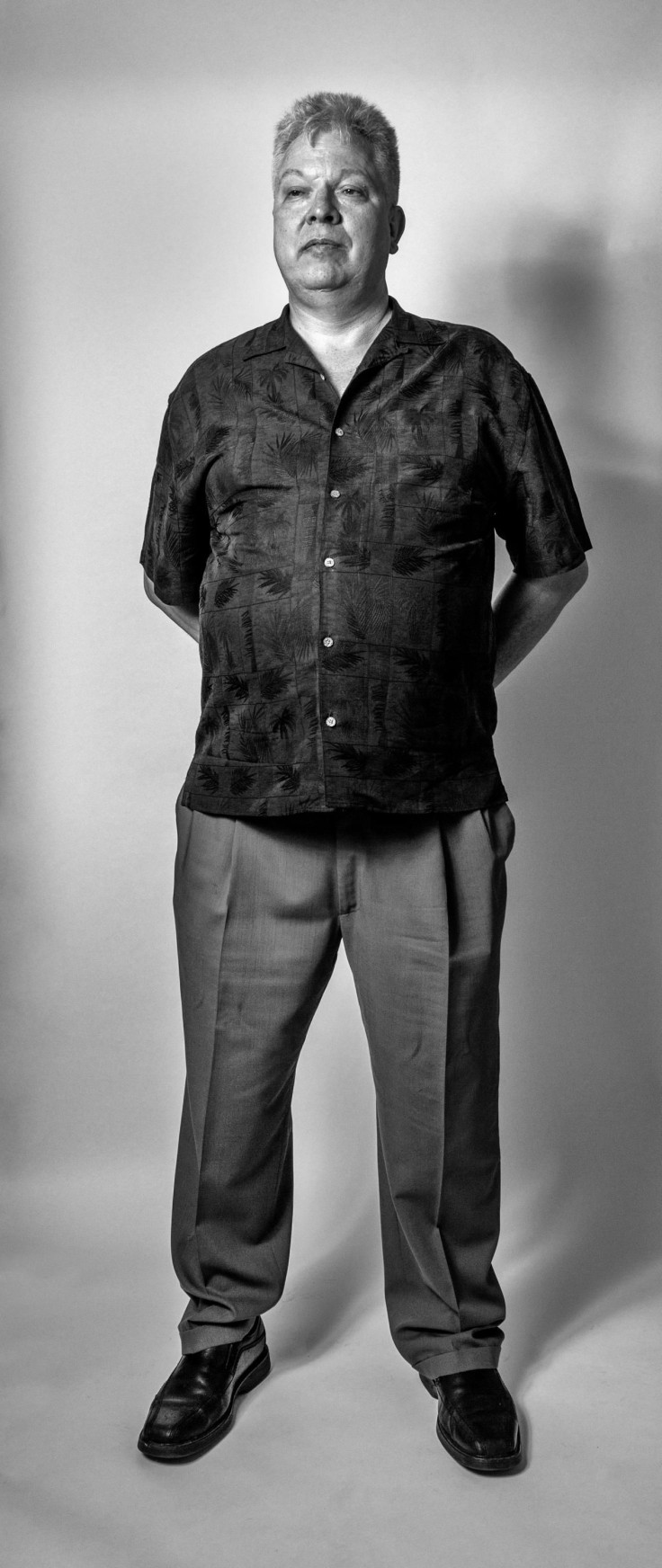

Gerasimczyk, the retired cop, vividly recalls standing feet away from the south tower when it fell. “We were right by St. Paul’s Chapel when the first building came down,” he says. “A nightmare. I thought, We’re already dead.” He had been dispatched downtown as soon as the planes hit. One of his supervisors, Timmy Roy, an NYPD sergeant, was radioing for help from the base of the towers. In the days that followed, Gerasimczyk and his colleagues searched the rubble for Roy and put him on the list of the missing. “We never saw Timmy again,” he says. “They found some bones. And they found his gun. It had melted.”

Paul Gerasimczyk, 57, is a retired NYPD police officer. He was standing at St. Paul's Chapel when first tower came down. "[It was] a nightmare. I thought we were already dead," he says. Now he suffers from, kidney cancer, for which he has had surgery, and precancerous conditions such as GERD.DEVIN YALKIN FOR NEWSWEEK

The grief he still feels over lost colleagues like Roy makes it painful to think about the anniversary of the attacks. “I can’t watch stuff on television about it,” he says.

Since 9/11, Soltes, the retired Port Authority officer, says he has struggled with claustrophobia, panic and fear of heights, in part because he saw people jump from the burning towers. Still, he does not regret the time he spent in the rescue efforts at Ground Zero. “If I’d had to watch that on TV without doing anything, it would have driven me out of my mind,” he says. “It was better for me to be down there.”

One night, as he dug through the rubble, he found a briefcase, completely intact. Inside was a pair of eyeglasses and a New York Times dated September 11, 2001. The man who had owned it was on a list of the missing, so Soltes and his colleagues were able to return it to the man’s family. “When I think about being down there, searching the rubble from 3 a.m. to 7 a.m.,” he says, “I know each and every one of us would do it again tomorrow.”

Despite his illness and the agonizing memories, Perez feels the same way. He never published the photos he took on 9/11. He keeps them as a way to try to heal and accept what happened. “I have gone to the site, and I take my photo albums with me. I think, I am standing right here, where I was standing then.”

Whether he will heal from the physical damage is less certain. “I only ask, Keep me in your prayers. Keep us all in your prayers,” he says. “We all need them.”

This story was originally published on newsweek.com.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.