Addiction 2016: As Heroin Use Escalates, A New Drug To Reverse Overdoses Hits US Drugstores [VIDEO]

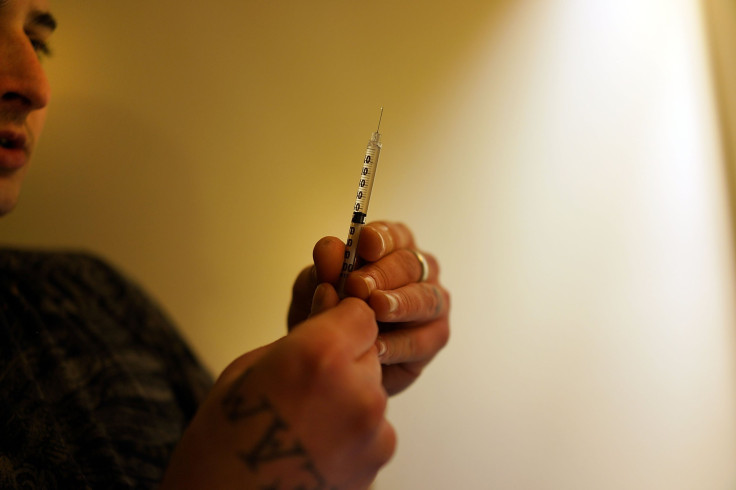

On the night Chris McClamroch overdosed on heroin, he and two friends were driving home from meeting a dealer in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. Unwilling to wait for his high, McClamroch shot up in the backseat of the car, injecting his usual 0.5 grams. But unbeknowst to him, this heroin was more pristine than most grades, which are often cut with cornstarch or laced with additives. McClamroch doesn’t remember much about the moments after he inserted the needle, but his friends tell him that within five minutes, he was unresponsive and breathing sporadically.

The friends rushed him to the hospital where nurses injected him with a drug called naloxone, which is commonly referred to as Narcan. A minute or two later, McClamroch was awake, though violently ill and suffering from extreme withdrawal.

“Thank God for Narcan,” he says. “If they wouldn’t have used that, I don’t know if I would be alive.”

Starting next week, drug users who overdose on heroin or other opioids such as Vicodin and Percocet won’t need needle-wielding doctors, nurses or EMTs to revive them. In 35 states, Narcan will soon appear as an easy-to-administer nasal spray that anyone can purchase at major drug stores without a conventional prescription.

The new formulation’s maker, Adapt Pharma, says the new nasal spray couldn’t come at a better time. Heroin’s popularity is on the rise and deaths from overdoses of the drug more than doubled from 4,397 in 2011 to 10,574 in 2014. Physicians, public health officials and even President Barack Obama point to naloxone as part of the solution. The drug, used mainly as an injectable remedy for 45 years, reverses an overdose’s effects, instantly bringing potential victims like McClamroch back to a stable condition.

Concern over heroin’s spread is generating a swell of public support for making naloxone more widely available, and unprecedented sales opportunities for the handful of companies that produce it.

“We believe this should be in every medicine cabinet out there,” Matt Ruth, chief commercial officer for Adapt Pharma, says.

Though generic naloxone has been around for decades, companies eager to earn a share of this suddenly competitive market have created patentable delivery systems for the product.

Privately owned Adapt Pharma says its version of naloxone, called Narcan nasal spray, is the easiest to use and most affordable to date. Adapt’s strategy is to distribute Narcan widely through as many pharmacies and physicians as possible.

The plan could be aided by a nationwide Obama administration push to double the number of healthcare providers who prescribe naloxone, as well as a CVS Health Corp. effort to expand the number of states where its stores sell naloxone to customers without a prescription from 15 to 35 in 2016. The drugstore chain told International Business Times it wants to offer customers Adapt’s new nasal spray as an option.

But public health experts and Adapt’s leadership say naloxone’s potential could be far greater. Just as schools and theme parks stock EpiPens to address sudden allergy attacks and every airport and shopping mall in the U.S. has an atrial defibrillator, Daniel Raymond, policy director at Harm Reduction Coalition, says the total market for naloxone could include any locale that might confront someone who has overdosed, from hospitals and schools to public libraries and fast-food restaurants.

At the very least, America’s roughly 12,000 local police departments and 14,500 addiction treatment centers are likely to stock it. Many have already shown interest. Mike Leyden, emergency services director for the Vermont Department of Health, leads a statewide pilot program that has put naloxone in 10 addiction-related facilities. “Naloxone is all about being in the right place at the right time,” Leyden says. “It doesn’t do any good in the medicine cabinet if you’re out in the world.”

Deputy Chief Mitch Cunningham of the Wilmington Police Department in North Carolina, says he thinks his group of 270 officers will be the fifth or sixth police department in the state to begin carrying naloxone. They will receive their first shipment of 250 units in the coming weeks. “We knew other police agencies were going to this,” he says. “I think it's generally becoming widely adopted.”

Part of naloxone’s appeal to companies is that it isn’t only meant for heroin users. It can also treat people who overdose on pain medicines, which is an even bigger problem than heroin in the U.S. Heroin and prescription painkillers attach to the same receptors in the brain. In fact, many patients become addicted to painkillers while recovering from surgery or treating chronic pain and switch to heroin once their prescription runs out.

Dr. Bill McCarberg, president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, says naloxone should be given to everyone who receives painkillers. If physicians wrote 10,331 prescriptions for naloxone in 2014, they wrote 479 million prescriptions for painkillers including refills, according to IMS Health. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is drafting guidelines for opioid prescribing that suggest physicians prescribe naloxone to high-risk patients with a family or personal history of addiction.

“The companies have an enormous opportunity,” Raymond at Harm Reduction Coalition says. “We’re hoping with these final guidelines, it sends a very strong signal that more doctors should start thinking about this.”

With the market for naloxone poised to reach new heights, Adapt and its competitors are seeking ways to position their version as the best. Today, generic naloxone comes in three forms. All three are easier to use, and more expensive than a standard $1 per dose injectable version widely used before the rise in heroin-related deaths, says Raymond. Virginia’s privately held Kaleo Pharma sells the most expensive option, a device called Evzio that automatically injects naloxone when pressed to a person’s thigh, for a wholesale price of $750.

But a publicly traded California company called Amphastar sells the most popular version — liquid naloxone in a syringe that many users pair with an atomizer to create an inhalable version of the drug. Amphastar has capitalized on burgeoning demand for its product, raising the price for a kit containing two doses from between $40 and $50 two years ago to its current price of $80 to $100, according to Raymond. For the most recent quarter ending Sept. 30, Amphastar said sales of naloxone had jumped to $10.5 million from $3.7 million a year earlier “as a result of increased unit volumes at higher average prices.”

Now, Amphastar faces a fierce new competitor. Adapt's Narcan nasal spray was designed through a partnership between the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the biotech company Lightlake Therapeutics Inc. The agency had noticed users were attaching Amphastar’s syringes to atomizers and wanted an FDA-approved intranasal version of naloxone. Lightlake then licensed Narcan to Dublin-based Adapt in a deal that Lightlake said could generate more than $55 million in sales and development payments plus “double-digit” royalties.

Studies have shown that Narcan nasal spray is easier to use and more efficient in delivering the proper dosage of naloxone than the rigged Amphastar product. Dr. Phil Skolnick, who oversees medical treatments for addiction at NIDA, says he can’t imagine why physicians would prescribe or recommend the old nasally administered version, now that Narcan nasal spray is available. “For me, it would be unethical to use anything else,” he says.

Amphastar did not respond to a request for comment.

Ruth at Adapt says the nasal spray has been “extremely well received” by insurers the company has spoken to about coverage. And Adapt is speaking with “every pharmacy chain out there” about carrying it, he says. Public agencies can purchase Narcan nasal spray at a discounted price of $37.50 per dose or $75 for two doses, just below the new price of an Amphastar kit and far below the price of the Evzio auto-injector.

Last week, Adapt said it would offer this rate to 62,000 state and local agencies and nonprofits through a formal purchasing agreement. Though agencies can also obtain Amphastar or Evzio through similar channels, Brian Namey, director of media relations at National Association of Counties, says his group is “particularly interested in Narcan because of its ease of use.”

McCarberg at the American Academy of Pain Medicine says he would actually prefer to prescribe the auto-injector, which provides step-by-step verbal instructions to users, because it’s “idiot-proof” but balks at the $750 price tag. He says some patients’ insurance plans cover naloxone, but not many.

Mark Herzog, vice president for corporate affairs at Kaleo, says the company is pleased that naloxone will become more widely available with the arrival of Narcan nasal spray. He points out how easy it is for panicked caregivers to use the Evzio auto-injector and says Americans with insurance can often buy it for less than $20.

Raymond thinks ease of use is key, but so is price. “The devices that are easiest to use and have that balance of affordability and accessibility are going to be the devices that succeed,” he says. Ultimately, he believes the market for overdose reversal treatments is so big that there will always be plenty of room for multiple products.

While Adapt can likely bet on ready-made demand for Narcan’s debut, it will also soon face competition in this fast-growing space. Amphastar is already developing its own ready-to-use nasal spray and so is Indivior PLC. But last summer, Adapt coyly acquired another advantage over its rivals.

Last summer, the company purchased the popular name for an undisclosed amount and dubbed its new product Narcan nasal spray. “Narcan is back,” Ruth says.

“That was really, extraordinarily clever,” Skolnick at NIDA says. “Everybody knows Narcan and nobody else can use that name.”

A smattering of community leaders have opposed making naloxone widely available to consumers, worrying that addicts will perceive it as a sort of insurance against overdosing. McClamroch in Louisville points out that receiving naloxone sent him into an intense and immediate withdrawal that he never wishes to experience again.

“Even when I was using hardcore, I would have never just voluntarily been like, ‘Let me just take double because I've got this Narcan and if I overdose, it'll save me,’” he says.

Today, 33-year-old McClamroch, who was 27 when he overdosed, works at a plastics manufacturing plant in Louisville and counts his recovery as one of his life’s greatest accomplishments. He hasn’t used heroin in more than six years. The night he overdosed, he says “was kind of my rock bottom, when I realized I really need to get clean.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.