Affordable Home-Ownership Scheme Offers A Pathway Out Of Social Housing

Social housing is in crisis in Australia, with almost 200,000 people on waiting lists. Social housing made up 8 percent of all housing stock in Australia in 1966. This had fallen to just 4.3 percent at July 2016.

As a result, governments have tightened eligibility. Social housing is increasingly home to only the most vulnerable households. And even these households often spend years on the waiting list while experiencing severe housing stress or homelessness.

Outside of social housing, rental and ownership options are increasingly unaffordable, particularly in the capital cities. Social housing was once a stepping stone to home ownership, but this is becoming more difficult.

What do the buyers think about it?

I interviewed ten of the 28 MAP households in our research and will be presenting findings next Tuesday, Oct. 9, at a free event.

Residents offered extremely positive feedback on their new homes and about being able to buy a home near their existing communities. They would not have contemplated this without the MAP.

Many had lived in social housing for 20 to 30 years and had never felt capable of making the move into market housing.

Participants spoke of the benefit of being able to pass on an asset to their children or to build wealth in their home. Many spoke of the great sense of achievement this move had given them.

I found residents retained extremely strong connections to their previous communities. They often returned to the public housing estates for social activities, to visit family and for community gardening.

However, many also spoke of their deep desire to leave unsafe, “aggravated” and uncomfortable previous homes. Households spoke of the deep sense of relief that came from feeling safe.

Most respondents told me their financial position had not changed or even improved since moving into MAP. Most were “over income” tenants, with a household income that meant they paid market rent for their social housing. Many found their mortgage repayments were similar to their previous rental costs.

However, social housing provides a “safety net” as rents are adjusted if household income decreases. Given some households gathered their deposits with significant support from family and friends while earning low incomes, this might be a future concern for residents.

Scaling up solutions

A 28-unit development is a drop in the ocean compared to the level of unmet need. Recent research suggests Greater Melbourne alone has a 160,000-dwelling deficit of housing that is affordable and available to very low and low-income households.

Creating a significant change requires effective models to be replicated and scaled up. In Toronto, a similar model called Options for Homes has delivered 2,000 affordable units. A further 2,500 units are in the construction pipeline.

Our research found this model is replicable and suitable for a subsection of more financially secure social housing tenants. Its scaling would be supported by access to land and finance and integration with social rental housing options.

Access to land

Access to affordable land in well-located areas is one of the largest barriers to developing affordable housing. Projects like MAP could be integrated into state government initiatives like the Public Housing Renewal Program.

Such schemes would also benefit from discounted land sales by philanthropic or religious groups, or even deferred land sale costs. Options for Homes almost always works with vendors that are prepared to defer land purchase costs until development is completed.

Access to funds

Philanthropic organisations and social impact investors like the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation have already supported affordable home ownership through the Affordable Housing Loan Fund. This allowed the not-for-profit organisation Habitat for Humanity to provide no-interest loans to low-income buyers in the town of Yea in Victoria.

Similarly, social impact investors are key to providing project equity to models like the Nightingale housing model. They could provide important equity and/or debt finance to projects using the MAP model.

Integrated housing solutions

This model is aimed at households with incomes of at least A$75,000 a year, or access to a substantial capital contribution. Despite the reduced deposits and mortgage repayments, most social housing tenants will not be able to access this scheme.

Other not-for-profit organisations could replicate this model and integrate it into their existing portfolios of social rental housing. The MAP model could cross-subsidise other housing options and help to provide a diversity of housing options in developments.

Why does this matter?

For the Melbourne Apartments Project, we estimated that for every A$1 of cost to the government, it receives A$2.19 in benefits from the project. This is mainly due to new households being able to move into vacated public housing units.

If every public housing unit made available as a MAP participant moved out were reallocated to a high-needs applicant on the waiting list, the government could save A$27,458.22 in costs per MAP participant per year.

Housing is increasingly unaffordable in many parts of Australia. As governments reduce their role in social and affordable housing, the need for industry-led innovations is growing. Pilot projects such as MAP are important but need to be supported by policy and scaling mechanisms to have a systemic impact on our housing environment.

There is a solution

The Melbourne-based Barnett Foundation responded by creating a model of affordable home ownership for social housing tenants. The foundation developed a 34-unit apartment in the inner suburb of North Melbourne and offered 28 units to households living within 4km of the site and willing to leave their social housing. It’s called the Melbourne Apartments Project (MAP).

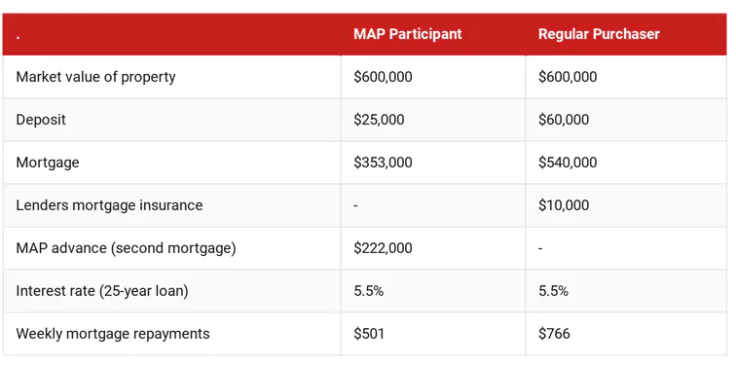

The foundation offered an interest-free second mortgage scheme to ease buyers’ transition into home ownership. This allows the owner to retain 100 percent ownership of their home while combining their own savings, a standard first mortgage with a bank and a second mortgage with the foundation.

The developer achieved cost savings during construction through reduced marketing and real estate costs (thanks to support from Melbourne City Mission), reduced tax requirements and foregone profit. The savings totalled about 37 percent of the market value of each property.

These savings were passed on to the buyers in the form of a no-interest second mortgage. This is not payable until the home owner sells their apartment. The second mortgage also reduces every year for the first four years.

Buyers were required to provide at least a A$25,000 deposit and to seek a mortgage to cover the remaining development costs of each unit. This is about 63 percent of market value, meaning they require a much smaller loan and pay less interest, as well as a smaller deposit. This helps overcome two of the largest barriers to home ownership for first home buyers.

Katrina Raynor is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Transforming Housing Project, at the University of Melbourne.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article here.