African Nations Cling To Fossil Fuels Despite Climate Call

African oil and gas producers are likely to pay little heed to the mounting clamour to scrap fossil fuels, the biggest driver of the world's climate crisis.

Adding to the pressure, the UN climate summit in Glasgow this month called for greater efforts towards a "phasedown" of unhampered coal emissions and "inefficient fossil fuel subsidies."

The call was diluted after hours of tortuous debate, but even so was historic. It marked the first time that a UN text made specific reference to the energy sources driving global heating.

But African producer nations may well turn a deaf ear to appeals for early curtailment of fossils.

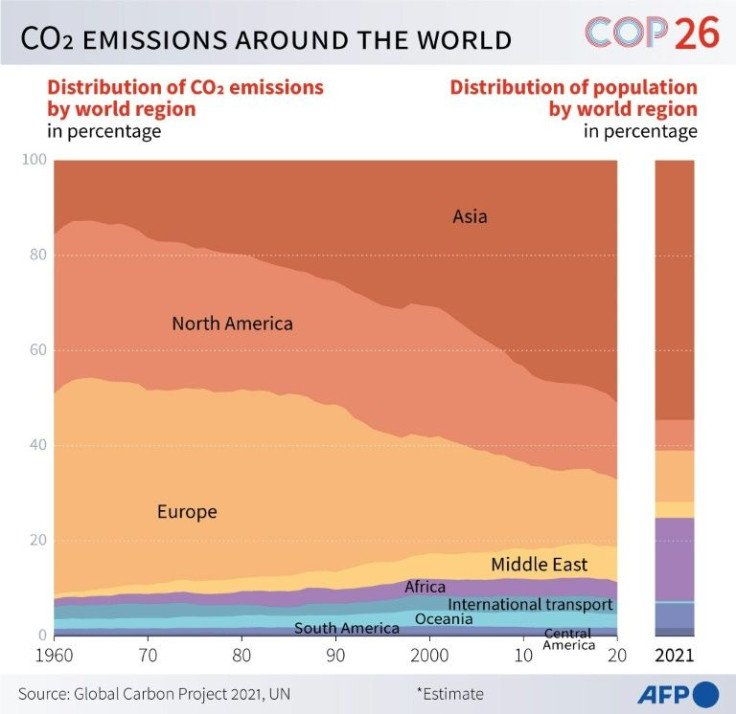

Compared to giant polluters, they are small contributors to the greenhouse-gas problem -- and many argue that renouncing oil and gas at this point could cripple development and deepen poverty.

"Limiting the development of fossil-fuel projects and, in particular, natural gas projects, would have a profoundly negative impact on Africa," Nigerian Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, whose country is Africa's major fossil-fuel producer, said recently.

Natural gas "is a crucial tool for lifting people out of poverty" in many African countries, he cautioned.

Osinbajo took up the well-versed argument that a global switchout from carbon-based fuels had to account for economic differences between countries.

For poorer countries, "the transition must not come at the expense of affordable and reliable energy... (and) the right to sustainable development and poverty eradication," he said.

But his widely-shared idea that fossil-fuel development helps eradicate poverty comes up against some hard facts.

In African countries that have had a bonanza from oil and gas production, little of the windfall has trickled down to the poorest, and suspicions of boundless corruption and sickening waste run deep.

In Angola, sub-Saharan Africa's second largest crude producer, oil accounts for half of gross domestic product and 89 percent of exports.

Yet more than half of the 34 million population survive on less than $2 a day, and the unemployment rate is at 31 percent.

President Joao Lourenco has launched an anti-corruption campaign aimed at netting billions of dollars he suspects were embezzled under his predecessor Jose Eduardo dos Santos.

"If one looks at the pattern of fossil fuels in Africa, it's very clear that it hasn't contributed" to development, said Mozambican environmental activist Daniel Ribeiro.

Instead, he said, "it increases debt, it increases corruption."

In his own country, the authorities have set down ambitious plans to exploit immense natural gas deposits off its northeastern coast.

Ribeiro accused multinational fossil fuel companies of using tax havens, with the result that Mozambique's economy will get little revenue from the expected boom.

Instead, benefits flow to the "ruling elite" and the Frelimo party, in power since independence in 1975, he charged.

That is why the Mozambican government are "really fighting against any kind of 'no to gas' movement," he said.

In West Africa, anger is growing in Ivory Coast among people who say they have seen little wealth trickle down to them after decades of oil and gas exploitation on the petroleum-rich coastline.

In late October locals blocked work to lay down a new gas pipeline.

"They have been extracting oil since I was born, and I live in poverty," said Duval Nevry, 27, in the village of Addah.

"I don't understand why a village that has an oil rig has no fire station and no secondary school, or why the hospitals don't have supplies," added Jean Biatchon N'Drin, 32.

If African countries are aware of the negatives of oil and gas, they also see relatively little help for switching to cleaner renewables.

The continent has huge potential in solar, wind and other green sources.

The International Renewable Energy Agency estimates that -- with access to the appropriate funding -- renewables could account for up to 67 percent of sub-Saharan Africa's electricity generation by 2030.

In 2009, rich countries promised to muster $100 billion a year by 2020 to help vulnerable countries tackle climate change.

The promise remains unkept, and is further clouded by debate about how the money should be allocated.

A dozen years ago, the expectation was that the funds would focus on helping developing nations transition to cleaner energy.

Since then, a string of catastrophic droughts and floods has spurred demands that funds be used more to shore up climate defences rather than reduce carbon emissions.

But this money would in any case be a fraction of what is needed.

Trillions of dollars, not billions, are needed just to adapt to the impacts of global warming, according to a draft report by the UN's science experts, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), scheduled for release early next year.

"The question of financing remains one of the major challenges to be taken up," said Cheikh Tidiane Wade, a Senegalese geographer specialising in climate.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.