After Sudan's Peace Deal, The Hard Task Begins Of Gathering The Guns

Sudan is celebrating a landmark agreement to end decades of war, but the first step to turn promises on paper into peace is also one of the most explosive -- disarmament.

Collecting weapons in a country left awash with guns after years of conflict in which hundreds of thousands died is one of most delicate parts of the October 3 peace agreement.

"Gathering the weapons is a very difficult business," said Gibril Ibrahim, commander of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), one of rebel signatories to the historic deal.

"It involves a collective effort. People will not hand over their weapons until they judge that the government can ensure their safety."

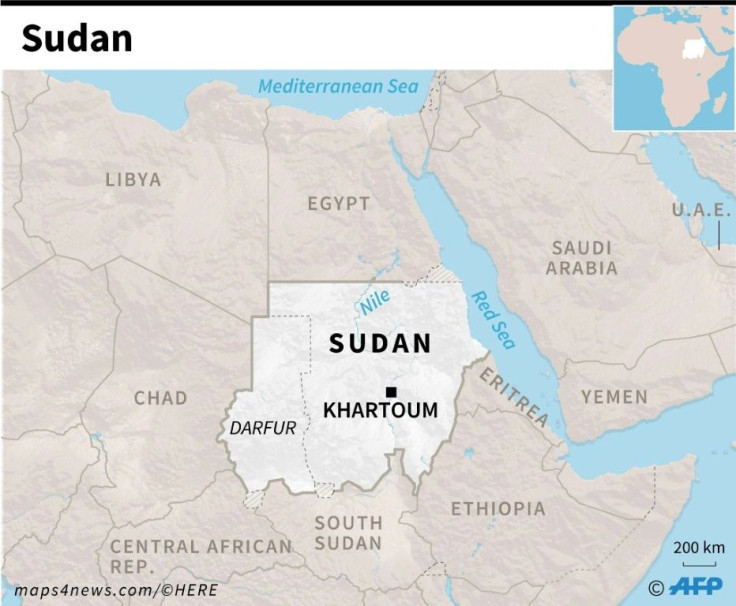

Ibrahim's JEM fighters battled Khartoum's government in the western region of Darfur, where fighting since 2003 left around 300,000 people dead.

"If we have a democratic government that listens to the voice of the people, people will conclude that they no longer need to carry arms to protect themselves," Ibrahim said.

The historic deal signed by the government and an alliance of rebel groups, the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF), was hailed by the international community as a milestone.

The rebels included groups from Darfur, as well as the southern states of Blue Nile and Southern Kordofan.

According to one rebel leader, it involves some 35,000 rebel fighters.

Peace was made possible after mass protests ousted president Omar al-Bashir from power in April 2019, and the transitional government has made ending the conflicts a priority.

Bashir, wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur, has already been convicted of corruption, and is currently on trial in the capital Khartoum for the 1989 coup that brought him to power.

The government has also agreed that Bashir will face trial for his role in Darfur.

But after so long at war, many are wary of giving up their guns.

"Trust is key to disarmament," said Jonas Horner of Brussels-based think tank the International Crisis Group (ICG).

"The military -- linked so closely with abuses during the Bashir government --- simply has not had the time nor shown the will to address violence in the way that many rural Sudanese would need to see in order to put down their weapons."

Warning of a "trust gap" between the ex-rebels and Khartoum, Horner said he feared some will keep a cache of weapons hidden as insurance.

Two holdout rebel groups -- including some 15,000 fighters, according to one estimate -- refused to take part in the October 3 deal.

One, the Darfur-based Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) faction led by Abdelwahid Nour, is believed to maintain considerable support.

Another, a faction of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) based in South Kordofan and led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu, has signed a separate ceasefire.

That deal allows the rebels to keep hold of their guns for "self-protection" until Sudan's constitution is changed to separate religion and government.

Even before the deal was signed, Sudan's army launched a mass disarmament campaign, blowing up thousands of firearms collected from civilians in a huge explosion in the desert.

The Small Arms Survey, a Geneva-based research organisation, calculates there were 2.76 million illegally-held weapons in Sudan in 2017, or 6.6 guns for every 100 people.

Rebels will be slowly incorporated into joint units with government security forces.

"For the stability of the country, the weapons must be handed over to the regular forces," said Yassir Arman, deputy chairman of the SPLM-N rebels who signed the deal.

Turning rebels into regular troops brings together old foes in often uneasy joint units.

"We must build a professional army which does not intervene in political affairs," Arman added.

Sudan has seen much-hailed peace deals crumble before, so this agreement lays out clear steps.

"The security aspect of the agreement is the most complex," said Mohammed Hassan al-Taichi, spokesman for the government negotiating team.

A "supreme council" will be created within 45 days to lead disarmament and the demobilisation of rebels.

"The collection of weapons will only take place when the rebels start to join the training camps," Taichi added.

In Darfur, the process should be complete within 15 months, but in other areas, a deadline is 39 months.

While building peace requires people to give up their guns, few will surrender their firearms until they are confident war has gone for good.

It is a tough conundrum.

"Until some semblance of sustainable peace is in place with a trusted central authority, there will be little incentive to comply with government-run disarmament programmes," Horner said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.