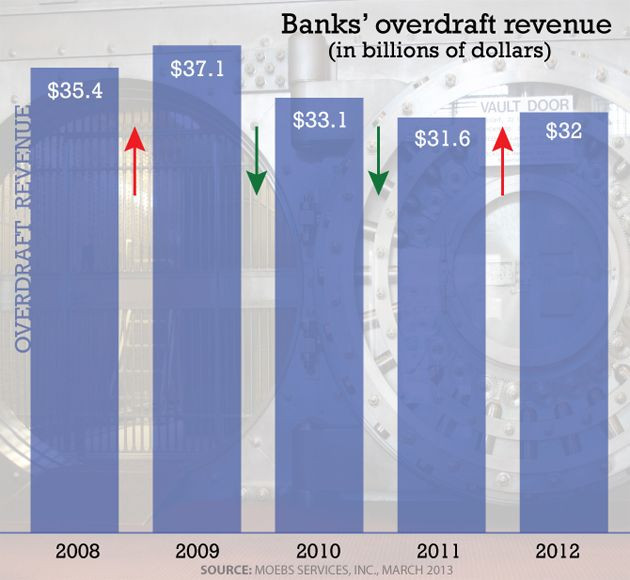

After Two Consecutive Annual Declines, Bank Overdraft Fees Are On The Rise, Again

Two years after the Federal Reserve ordered banks to stop forcing “overdraft protection” on customers that don’t want it, banks in the U.S. have managed to put an end to the declining revenue from fees they charge customers who withdraw more than their checking or savings accounts hold. Following two annual declines in revenue derived from these fees, bank customers shelled out $400 million more in 2012 than they did the previous year, according to a report by economic research firm Moebs Services. Last year banks operating in the U.S. raked in $32 billion on overdraft-fee revenue, down from $37.1 billion in 2009.

Banks consider overdraft protection a courtesy that prevents customers from having their debit card transactions blocked for lack of funds. Critics say the fee is predatory, because it applies exclusively to low-balance customers who live paycheck-to-paycheck and involves high per-transaction fees that amount to usury. Prior to the Fed’s July 2010 decision, customers could not opt out of the service at many banks.

The Moebs study estimates that about one in four checking accounts, about 38 million, are frequently overdrawn. Twenty million customers rely on payday lenders for their overdraft transactions compared to 18 million that use banks or credit unions, mainly because payday lenders actually charge less than banks -- $16 per $100 advance compared to the average $30 for banks and $27 for credit unions. Overdraft limits are typically no higher than $1,000 and most overdrafts are for much smaller amounts, according to bankrate.com.

The study also pointed out that the fees charged by banks varied by the size of the bank. Banks with smaller total valuation charged lower fees compared to their larger competitors. The difference between the lowest and the highest is about $10 per transaction. That's not loose change to people whose accounts approach zero up to the next payday.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.