After Ukraine Cyberattacks, FBI And DHS Urge US Power Companies To Develop Better Safety Protocols

Just after 2:30 p.m. on Dec. 23, 2015, a freezing day in Western Ukraine, an unknown hacker logged in to the Ivano-Frankivsk’s computerized electrical grid control center and, in a few seconds, abruptly shut down all electricity to the area’s 225,000 residents. The effects were immediate and far-reaching. Traffic lights turned off. Televisions powered down. As night fell, the area plunged into darkness — no lights, no heat. It was a complete blackout.

After about six chaotic hours, electrical workers in the area were finally able to restore power to the region. Although no one was hurt and the damage was relatively minor, this cyberattack — the first to successfully take down a major power grid — has caused significant backlash in the United States intelligence community and among lawmakers around the country.

“If the goal of the ‘bad guys’ is to collapse the U.S. economic system, they are going to try to cut off the power,” Rep. Lou Barletta, R-Pa., said at a subcommittee hearing of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee last week. “Our national security, public safety, economic competitiveness and personal privacy are at risk.

For over a decade, hackers have managed to breach banks, insurance companies, government databases and thousands of businesses in the United States. But this is the first time hackers have successfully breached a major power grid, and the implications for national security are huge. Cybersecurity experts have warned that a potential cyberattack against the country's power grid could have devastating effects, and this Ukrainian hack proves their point.

Caitlin Durkovich, assistant secretary of Homeland Security for Infrastructure Protection within the National Protection and Programs Directorate, echoed Barletta’s thought. “A targeted cyber incident — either alone or combined with a physical attack — on the power system could lead to huge costs and cascading effects, with sustained outages over large portions of the electric grid and prolonged disruptions in communications, water and wastewater treatment services, healthcare delivery, financial services and transportation,” she said.

In January, a team of U.S. officials (including investigators from the FBI, Department of Homeland Security and Department of Energy) traveled to Ukraine to interview workers at the substations affected by the hack. They discovered that about six months ago, an unknown individual used a common spear-phishing tactic to obtain login credentials of a power plant employee. Then using a common remote login software the hacker was able simply to log in to the area’s power grid and shut down circuit breakers, one by one, that affected the region’s electricity.

Mark Bristow, the chief for incident response and management at the Industrial Control Systems Cyber Incident Response Team, explained at a recent security webinar how, exactly, the hacker gained control of the power grid in Ukraine. Bristow noted that this wasn’t even a particularly sophisticated attack — in fact, the hacker did not inject a malicious code to disable the power grid. Rather, it was the work of one or more individuals who simply gained access, logged in and shut down the power — and then changed the passwords.

“It was not done by code,” Bristow said. “It was done by a human.”

In direct response to the Ukrainian cyberattack, both the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department Of Homeland Security (DHS) have teamed up to launch a series of briefings around the country titled “Ukraine Cyber Attack: Implications for US Stakeholders” to educate security personnel, energy executives and local government officials on “strategies for mitigating risks and improving an organization’s cyber defensive posture,” according to a government document posted online.

There will be eight in-person briefings and four online webinars held in April.

According to Bristow, to make matters worse, the hacker then disabled the telephone communication networks to make it more difficult for the electrical workers to communicate with one another and get the system back up and running. According to Stewart Kantor, the CEO and a co-founder of Full Spectrum Inc., a wireless telecommunications company, this was a major flaw in the system. Kantor says that if there’s ever a data breach on a critical system, having a protected line of communication that doesn’t run on any public Wi-Fi is an essential need, especially for a power company. “The hackers hijacked the systems and locked the utility out and then controlled the grid,” says Kantor. “To the extent that utilities are relying on public communications networks they are vulnerable to this and other reliability issues.”

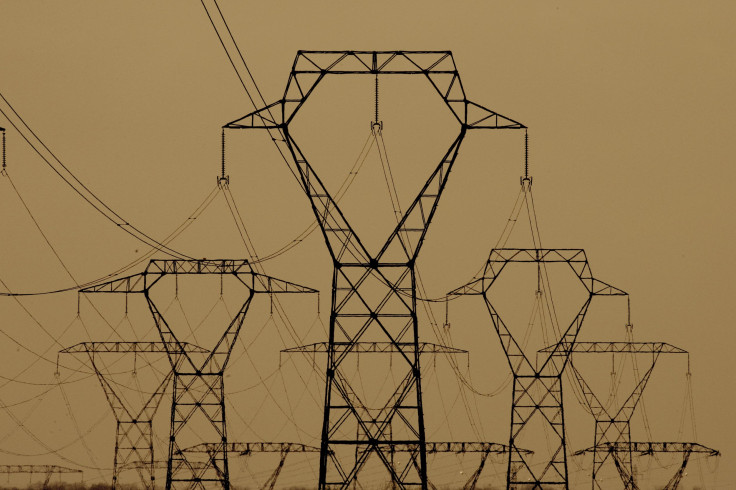

For years, U.S. officials have been aware that our electrical grid — the largest interconnected machine on Earth, containing 200,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines — is susceptible to physical attacks. In 2013, for instance, a team of gunmen opened fire on Northern California's Metcalf Transmission Substation, damaging 17 transformers.

But more recently, the threat of a cyberattack has loomed as more and more power companies have automated their controls and shifted their systems to the cloud. The DHS, for instance, says the energy sector is the target of more than 40 percent of all reported cyberattacks.

“We are accustomed to cyberattacks that result in grand larceny. We are accustomed to cyberattacks that amount to huge vacuuming of intelligence information. What we've never had is a cyberattack that amounts to a weapon of mass destruction," Ted Koppel, who has written a book, "Lights Out," about the threat of cyberattacks on the electric grid, said recently. "If someone succeeds in taking down one of our power grids ... it would be devastating.”

Clearly, while automation has resulted in cheaper energy for customers and more efficiencies for power companies (i.e. the need for less manual labor), some energy experts suggest that this trend leaves much of the power grid susceptible to cyberattacks like the one in Ukraine.

“The electric grid, as it moves more and more to automation, we don’t have the manual workers we did 25 years ago to go turn everything back into a manual system,” says Professor William Arthur Conklin, an energy and infrastructure expert at the College of Technology, University of Houston.

“We used to have one guy in each control room,” he adds. “Now they have one guy sitting in a control room that six guys used to monitor.”

Part of the problem of protecting the electrical grid, says Conklin, is that implementing wide-scale security protocols are expensive for utility companies, and because energy prices are heavily regulated by the government, finding money in the budget for security can be difficult for utility companies. “You can’t get a rate hike until you’re beyond the point of needing it,” he says. “It’s not a matter of you don’t want to do security. It’s until the government mandates it and says, ‘Thou shalt do this,’ ... a utility company is in a position of not being able to win.”

In the meantime, the briefings assembled by the DHS and FBI are intended to provide some basic security tips for people whose job it is to protect the system. According to Bristow, companies should have “basic defensive procedures” in place, like multifactor authentication for remote access. It’s also important to understand how to contact power grid employees in the event of a breach.

In addition to more complex passwords and authentication procedures, companies are being advised to implement precise plans in the event of a breach, and ensure communication back-ups in the event that a cyber attack targets internal phone lines , as well. The government is also advising companies to keep up-to-date on the latest malware bulletins circulated by U.S.-CERT. It's possible, however, that these suggestions might be too little too late.

For lawmakers like Barletta, a cyberattack on the power grid could result in devastating circumstances. He says that while many people may be prepared for an electrical outage that could last a few days, a major cyberattack on the power grid could last weeks, if not longer.

“These are new, complex and ever-changing challenges that we are facing, as terrorists continue to develop technological expertise,” Barletta said. “As a former mayor, I know that the people in the small towns and cities will be the first ones called on to respond in the event of an attack on our power grid. Local municipal leaders and states must continue to anticipate all types of disasters, because they are the ones who are tasked with some of the most important components of the response and recovery.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.