After A Year Of Gun Violence In America, Victims Debate Whether Gun Control Is The Answer

As the sun started to rise over Smith Mountain Lake in Moneta, Virginia, Vicki Gardner surveyed the fading darkness and thought to herself: “What an absolutely beautiful morning.” Clad in a white suit jacket, Gardner was standing on a balcony at the visitor’s center overlooking the lake community, with its 500 miles of shoreline, that she has called home for 30 years.

She was having fun speaking live on air to reporter Alison Parker about the celebrations planned for the 50th anniversary of the lake when she noticed some movement, something that looked like a person walking toward them.

Then a light went on and Vester Lee Flanagan II, 41, a disgruntled former co-worker of Parker's, fired shots as he recorded the scene on his cell phone camera. Parker, 24, and cameraman Adam Ward, 27, both died that day. Gardner, who was shot in the back, was the lone survivor.

“It was so hard to even understand what was happening. You see the fire coming out of the gun over and over,” said Gardner, 63, recalling the early August morning. “I saw evil and I saw the worst [that] mankind can conjure up.”

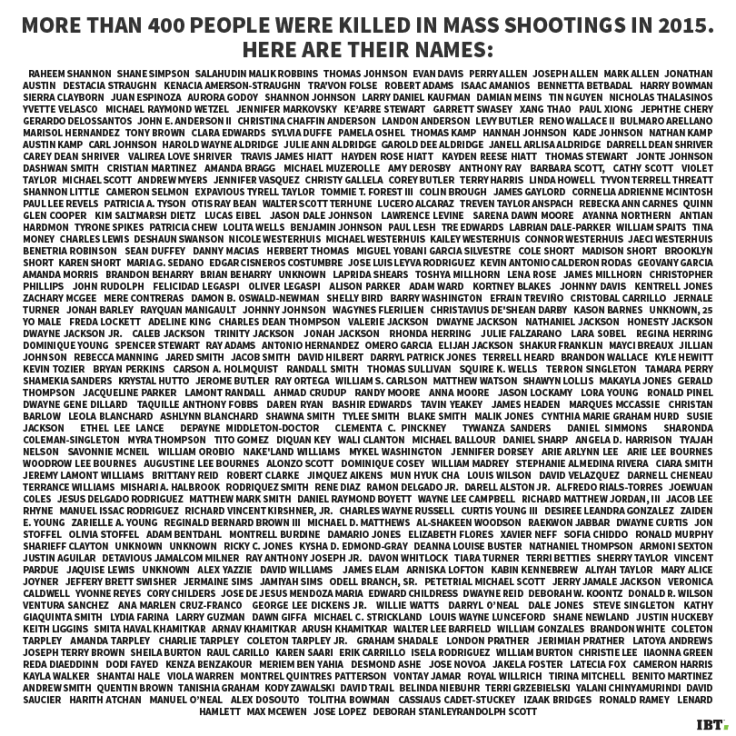

There was more than one shooting death per day in the United States this year, according to data from the Mass Shooting Tracker, which counts incidents where four or more people are either killed or injured by gun violence. The mass shootings turned once little-known cities and towns into household names as the nation united time and again to mourn together – Chattanooga, Tennessee; Lafayette, Louisiana; Roseburg, Oregon; Colorado Springs, Colorado; and San Bernardino, California, were only part of a long list of targeted communities. In the aftermath, survivors, families and community members said they were unsure what should be done to prevent further attacks, while advocates on both sides remain at odds over policy solutions, signaling that a year of increasingly routine violence has done little to settle the national debate on gun control.

“On almost every conceivable metric we surpass each and every civilized culture in the world in terms of gun violence,” said Ronald Sullivan, a clinical law professor at Harvard, who has focused on gun violence for more than 20 years. “I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say we have a problem of epic proportions and one that needs to be addressed and addressed quickly.”

Research from the Pew Center in Washington, D.C., shows that 85 percent of Americans favor expanding background checks and 79 percent support legislation that would prevent people with mental illness from being able to buy guns. When asked about a ban on assault-style weapons, support narrowed, with 57 percent saying they would support such legislation.

After a mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, three years ago left 26 dead, calls were made for policy reform and increased legislation. On this year’s anniversary of that massacre, President Barack Obama wrote a lengthy Facebook post pointing the finger at Congress for not enacting new legislation.

But advocates who have been fighting for stricter gun control said this year's flood of mass shootings was merely a continuation of the gun attacks that have unfolded in public spaces day after day in recent years. With shooters having diverse motives — including gang violence, disputes with co-workers and classmates, mental health problems and Islamic State group ideology — it’s difficult to construct a profile or pattern to the gun violence that in many ways defined in 2015.

“People are seeing a repeated pattern of horrific mass shootings with zero policy response from the political level,” said Tim Daly, director for campaigns at the Center for American Progress, a progressive research and advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. “You see this absence of leadership and it is really setting the stage for 2016.”

Roseburg: The Aftermath

Had it been a Monday, Wednesday or Friday, Alicia Graves, 33, would have been in a technical writing class in Snyder Hall classroom 15 at Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon. But it was Thursday, Oct. 1, and the journalism major was in another building when Christopher Harper-Mercer, 26, opened fire in the classroom, killing nine people and injuring nine before turning the gun on himself in the deadliest shooting in Oregon’s history. His motive was unclear.

Graves waited under lockdown, huddled with approximately 25 other people in a classroom as “time just disappeared.” The managing editor of the campus newspaper, the Mainstream, kept checking her phone to keep everyone updated as rumors swirled that there might be more than one shooter. When they heard a professor was among the dead, the teacher in the classroom with Graves broke down and panic spread. Graves estimates she was in the locked classroom for more than an hour.

More than two months later, at the end of her second term, Graves, a native of Roseburg, says the community that never had the feel of a close-knit college town has come together, with funds set up to help survivors and victims, and restaurants offering people free meals and cups of coffee.

“There’s a much greater sense of community now than there was, and people understanding that just because it hit the college it affects everyone here,” Graves said. “This last term was really hard for everyone. If you didn’t drop out you were struggling in one of your classes and so were the teachers.”

Graves said she has largely tuned out the other mass shootings that have occurred since Roseburg because they bring up flashbacks and panic attacks.

“We have some incredible survivors that aren’t getting the attention they need,” Graves said. “The survivors – there were some really severe injuries that came out that day and they are struggling every day to put their lives back together. [Others] may not have been hurt physically, but they were hurt emotionally and need to be given credit for being courageous.”

Paula Usrey, an associate professor of communications at Umpqua Community College, heard the gunshots from her office in Snyder Hall, where she hid under her desk before being escorted off campus by police. Usrey made a point of telling her students when they returned to campus after the October shooting that she had gone to see her primary care provider the next day to discuss what had happened. She modified assignments and regularly met with students to discuss the gun attack. As time passed, more laughter slowly returned to campus, she said.

“This isn’t a club we wanted to join, but we are in this together,” Usrey said.

Lafayette: 'Learning To Live Again'

Getting back into her daily routine was important for Dondie Breaux, 45, even if that meant crying while working out at her local gym. Everyone around her knew why she was tearing up as she exercised. In the tight-knit community of Franklin, Louisiana, with a population of less than 8,000, residents recognized her daughter, Mayci Breaux, as a smiling young woman who was just beginning her adult life. The 21-year-old was killed July 23 after John Russell Houser, 59, opened fire for unknown reasons during a showing of the movie “Trainwreck” in Lafayette, Louisiana. Jillian Johnson, 33, was also killed and nine other people were injured, including Mayci Breaux's boyfriend, Matthew Rodriguez.

“We are learning to live again. It is hard at times. She was at that age, she was my best friend,” Dondie Breaux said. “It still doesn’t feel real. Sometimes we just think she is out of town. It’s something that every mother and father shouldn’t have to go through, especially at the hands of another person.”

Mayci Breaux was a student at Louisiana State University at Eunice who was training at Lafayette General Hospital in radiology and also working at a clothing boutique. Her mother described her as a “bright light” with a “soft heart” who was family-oriented and looking forward to starting a family of her own. She loved going to the movies.

Scholarship funds have been set up in Mayci Breaux's name and an amphitheater in her hometown of Franklin is being renamed in her memory. “It’s the biggest thing that has hit our little town,” Dondie Breaux said. “Everybody has come together. It has changed dramatically. … They would do anything for us. They all knew us. She was a big loss in our town.”

For Dondie Breaux, it wasn't the theater or the gun that killed her daughter. It was "an ill man." She wants to see stricter background checks but does not support broad gun control. She said she would like to own a gun for personal protection.

“It’s just getting worse. I know everybody is mad at people with guns, but people have always had guns,” Dondie Breaux said, whose family owns guns. “It’s the mentally ill that aren’t getting help. People don’t know how to handle anger anymore.”

Roanoke: Not Moving On, But Moving Up

After the on-air fatal shooting, the WDBJ-TV studio in Roanoke where Parker and Ward worked renamed its news studio in their honor – Studio A for Alison and Adam. All 109 people who work at WDBJ were thrust into the strange position of having to cover the murder of their own colleagues as they watched it play out on live television.

“Recovery is slow and if you try to speed it up you make it worse,” said Jeffrey Marks, president and general manager of WDBJ, who went on air to address the community minutes after the deadly shooting. “Our goal should not be to move on but to move up and aspire to better … as Alison and Adam did.”

Marks says the shooting was “the most horrible year of my career and everyone here.” He said it’s the media’s responsibility to continue covering gun violence from all angles, including gun control policy.

“We need to cover the heck out of those issues,” Marks said. “It’s not our job to take sides.”

Colorado Springs: Normal Life Returning

But mass shootings across the U.S. have left some local residents struggling to figure out what could have been done to stop the violence and what else could be done to stop future attacks. In Colorado Springs, Colorado, Robert Lewis Dear, 57, killed three people and wounded nine when he entered a Planned Parenthood clinic Nov. 27 and used a semiautomatic rifle. A profile of an angry and disturbed man has emerged through court documents and interviews.

The surrounding area near the Planned Parenthood was put on lockdown after the shooting. Paul Lambert, 63, co-owner of Steins and Vines, a liquor store just a four-minute walk from the clinic, stayed in his office with another employee doing work and checking the news before being evacuated by police.

“I don’t know if anymore gun control laws would have stopped this from happening. I think this gentleman had mental issues,” Lambert said. “If he didn’t have guns he would have found another way. It’s just too bad that there are people out there like that.”

Lambert says normal day-to-day life is returning to the area but people still come into his store and ask him about the shooting.

“I was asked why I opened that Saturday and I said I’m not going to let someone like that dictate my life or business,” he said.

Charleston: An Unexpected Advocate

Meghan Alexander, 44, was getting her son ready for soccer camp when she heard the news that a mass shooting had taken place at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in the heart of Charleston, South Carolina. The marketing and public relations professional started crying as she watched the news that nine people had been killed on the evening of June 17 in what she describes as the “most tender of places for us Charlestonians.” Authorities said Dylann Roof, 21, carried out the attack because he wanted to start a “race war.” Roof was able to obtain a gun due to a breakdown in the background check system.

Alexander had never been an advocate for closing loopholes that allow for the sale of firearms online and at gun shows. But she saw how gun violence affects families when a college classmate lost a child in the Dec. 14, 2012, mass shooting in Connecticut.

In the aftermath of Charleston, almost everyone with whom she spoke about the racially motivated shooting wanted to do something. “People have reached a tipping point,” said Alexander, who moved to Charleston in 1998. “They don’t want to feel helpless anymore.”

Alexander became, in her own words, “an accidental activist” when she founded the new group Gun Sense SC. She readily admits that before she began her own research, she knew little about legislation or statistics. Now she rattles off a stream of facts, including that South Carolina is No. 6 in the nation for the legal sale of guns later exported outside of the state and used in crimes.

The group, with the tagline “saving lives, preserving rights,” aims to educate citizens and legislators about gun legislation and existing laws and advocate for legislation at the state level that would close loopholes for gun sales and mandate background checks before any gun sale is completed. In memory of those killed in Charleston, a nationwide Stand-Up Sunday event is being planned for Jan. 31, with more than 1,100 religious groups reaching out to discuss gun violence in their communities.

For Alexander, who counts gun owners and hunters among her own family members, it has been important to involve gun proponents. Two gun owners sit on the group’s board.

“I thought no one was out there talking to gun owners in our state … people who are also concerned and want to close loopholes,” she said. “The worst thing we can do is stand behind our differences and throw things at each other, especially in an election year.”

The 2016 Gun Policy Debate?

Within 24 hours of the movie theater shooting in Lafayette, a community center had been set up and professional counselors had arrived. It was part of the city’s insurance policy in the event of such a disaster. Lafayette’s three-term mayor, Joey Durel, 62, now tells officials in other areas to always be prepared.

“What happened in Lafayette will probably never, ever, ever happen in your community, but it could,” Durel said. “As mayors, city councilmen, don’t skimp on equipment and training for your police department, treat it as insurance.”

Durel still lauds his city as being named one of the happiest in the U.S. in 2014, with hundreds of miles of fiber-optic cables that deliver fast internet speeds. Now the theater shooting is part of the history too. After a gut renovation, the movie theater in Lafayette reopened and Durel says that the community has mostly returned to normal.

The horrific event hasn’t changed the conversation on gun violence for groups on the far left and far right in Lafayette. Durel argued that a discussion on gun control is a simpler one for politicians to have than addressing complex issues of mental illness, drugs and other environmental factors.

“The real issue is much more complicated and they don’t know how to deal with it,” he said.

With little political will in Congress to tackle the issue of gun violence, individual states have taken steps, with Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy announcing earlier in December he would sign an executive order that would bar people on U.S. terror watch lists from buying firearms. Nevada will have a ballot initiative on background checks next year and it’s possible that one could make it onto the ballot in Maine. There’s also a ballot initiative in the works in California that proposes banning large-capacity magazines as well as mandating people to report lost or stolen firearms to law enforcement. Currently eight states and the District of Columbia require point-of-sale background checks for all firearms.

With the 2016 presidential election less than a year away, advocates said they hope gun violence will be a main issue during the campaign season, but questions remain if much substance will come out of candidate debates.

“Can we for the first time historically develop single-issue, gun-violence-prevention voters?” asked Ladd Everitt, director of communications at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, an advocacy group based in Washington. “Now might be the time in our nation’s history to go single issue and say it’s no longer good enough.”

Sullivan, the Harvard professor, said a debate over constitutional rights and the rural-urban divide in the U.S. have limited national discussions on Second Amendment laws.

“We do live in a large and diverse country and guns are a normative part of very many parts all around the country as far as hunting and shooting ranges,” Sullivan said. “People believe the problems of New York City shouldn’t be permuted to a rural area. The two sides are not talking to each other very well. My view is it’s a national problem, we see it popping up in rural and urban areas.”

Groups advocating for the right to bear arms continue to question the need for expanded background checks. Dave Workman, communications director for the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, based in Bellevue, Washington, says his group doesn’t view background checks as a panacea and argues that many people who have committed mass shootings have passed such checks.

“Politically it’s a toxic subject. We are seeing an interesting phenomenon here during this early campaign cycle – guns have become a central campaign issue,” Workman said. “It’s really hard to put a finger on why. From the perspective of the gun community, firearms are an American tradition, just like hunting, self-defense and self-reliance, those are part of the American fabric. It’s puzzling to a lot of people that so many of their neighbors are willing to reject that.”

A Long Recovery

Gardner, executive director of the Chamber of Commerce in Smith Mountain Lake, has undergone three surgeries since being shot and is still on the road to recovery. She used to run for miles but says these days she says she feels like “Jell-O,” and is not sure things will ever be quite the same.

A day of remembrance was held for reporters Parker and Ward who died that August morning. Hundreds of people wore blue #SMLStrong T-shirts while locking hands across boats on the lake and the plaza where the attack occurred. A helicopter dropped white rose petals over the whole area. Donations poured in after the shooting and now a community center, dubbed “Vicki’s Vision,” is in the works. A memorial with a telescope shows the view of the lake both Parker and Ward had from their vantage point on the day of the shooting.

“We are going to be a better and stronger community,” Gardner said. “We can’t bring back those two young reporters, there’s nothing we can do to fix that aspect. … [There is] joy in that we found a way of making this horrible thing a little better.”

As Gardner lay recovering in the hospital from her injuries she flipped through TV channels, but after each one showed gun violence, she turned off the set. When she thinks about the different motives in cases ranging from the school shooting in Littleton, Colorado, in 1999 to the terrorism-related massacre in San Bernardino, California, this month, she said the answer to stopping gun violence continues to elude her.

“If I had the answer I would be shouting it from the mountaintops,” Gardner said. “I hope someone has the one-size-fits-all that will make a difference. … It’s hard to sit and watch all of this. My heart just goes out to the people and families.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.