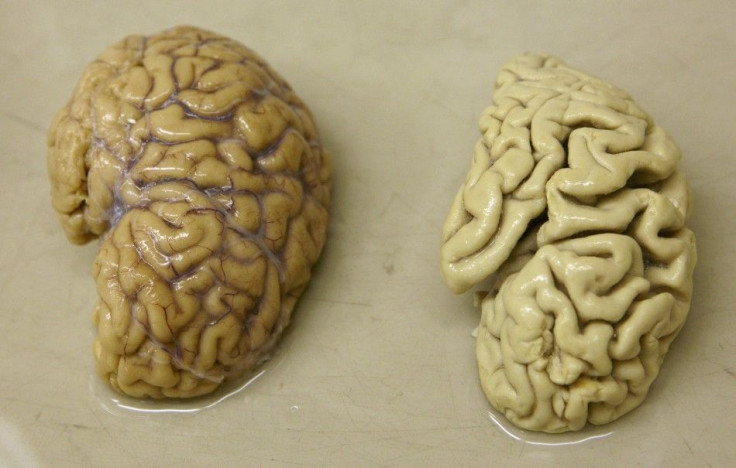

Alzheimer’s Detected 20 Years Before Symptoms, Study Shows

Researchers may have found a way to detect Alzheimer's disease up to 10 or 20 years before symptoms occur and can potentially treat the disease more effectively to slow down the effects.

After studying families with an inherited form of the disease, researchers from Washington University School of Medicine have found some signs that Alzheimer's can appear in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) much earlier than when a person is diagnosed.

The findings are a segue to helping detect Alzheimer's disease in those who suffer randomly with no apparent family history and hence treat all victims faster and more effectively.

Dr. Randall Bateman, director of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's Network (DIAN) at Washington University, and his team have recruited 184 family members who carry a mutated gene passed on through their parents which indefinitely causes Alzheimer's. This form of the disease called dominantly inherited Alzheimer's consists of patients who will inevitably be affected by the disease with symptoms beginning as early as age 30.

Though this version of dominantly inherited Alzheimer's is very rare, affecting only about one percent of Alzheimer's cases, those affected are the most promising to study since they will most likely inherit the disease and can be studied from the get go to determine early signs.

Dr. Bateman reported at the International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease on Wednesday in Paris that his team at Washington University has found ways to predict the early signs of Alzheimer's, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Alzheimer's begins with high amounts of tau proteins and low amounts of a precursor of beta amyloid in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Researchers found that children who have inherited the mutated gene to cause Alzheimer's have the same ratio of proteins in their CSF. They also found that the proteins in these same children reverse up to 10 years before Alzheimer's symptoms develop, mimicking the same levels of proteins common in Alzheimer's patients.

Since there are currently no drugs that effectively slow the progression of Alzheimer's disease, current Alzheimer's medications will be used on these patients with the mutated gene in the hopes drugs can slow down or possibly even block the stages of Alzheimer's for all cases of the disease.

The team at Washington University will test medications on the family members with dominantly inherited Alzheimer's in hopes that their findings can help all patients that suffer from Alzheimer's disease.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.