Amazon: Nearly 20 Years In Business And It Still Doesn't Make Money, But Investors Don't Seem To Care

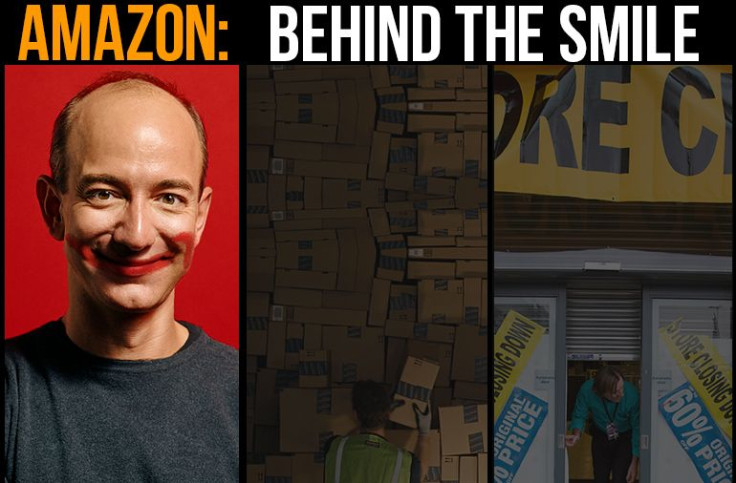

This is the first of a three-part series examining Amazon’s business model. On Thursday, we will probe the company’s labor practices, and on Friday we will explore the company's impact on small retailers.

So what's with Wall Street’s love affair with Amazon.com?

The company barely ekes out a profit, spends a fortune on expansion and free shipping and is famously opaque about its business operations.

Yet, investors continue to pour into the stock, pushing up the company’s share price to $388, a nearly 400 percent rise since the end of the company’s third quarter in September 2008.

At that time, Amazon’s net profit margin was 2.8 percent. By September 2011, that number fell to 0.6 percent. A year later, it was losing $274 million on net sales of $13.8 billion. And in the latest quarter, ended Sept. 30, the massive e-tailer reported a $41 million loss on $17 billion in sales.

The net result of nearly two decades in business is that Amazon’s trailing 12-month price-to-earnings ratio stands at an alarmingly high 550. Compare that to consistent profit earners with significant online retail operations such as Google (p/e 29), Wal-Mart Stores (2) or eBay (25), and it’s easy to be confused by investors’ hunger for Amazon.

Even Amazon’s strongest supporters can’t explain it.

“People have been buying ‘AMZN potential’ for a decade,” noted James Walker, a lecturer of business statistics at The King’s College in New York, in an email. He owns Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) stock because he’s certain that he can sell it at a higher price than when he bought it. Walker expects that trend to continue as “AMZN continues to execute well toward becoming the world’s largest ‘store.’”

Investors like Walker may be bullish, but some insiders at Amazon apparently are becoming a little more restive, which is never a good sign.

Since the company’s third-quarter earnings were released on Nov. 25, 10 of the company’s high-rolling insiders sold nearly 100,000 shares, not including the 1 million shares CEO and founder Jeff Bezos unloaded between Nov. 1 and Nov. 5, raking in more than $350 million. Among the sellers were Amazon’s Chief Financial Officer Thomas Szkutak, who sold nearly 12 percent of his stake in the company, and Jeffrey Wilke, senior vice president of Amazon’s consumer business, who parted with about 20 percent of his shares.

The Amazon insiders wouldn’t comment about why they sold the stock, but they may be concerned about how well the shares will hold up after the e-tailer’s fourth-quarter report in January. Estimates for Amazon earnings in the all-important holiday period have declined 10 percent to 66 cents per share, according to analysts surveyed by Thomson Reuters.

The forecasts are declining in part because Amazon is cutting prices ferociously on its products as Christmas shopping picks up, to levels that are break-even or below. For example, on Cyber Monday this year, Amazon slashed the prices of its Kindle Fire by upwards of $50, a savings of nearly 33 percent in some versions of the LCD tablet. And although Amazon is tight-lipped about Kindle sales, Bezos admitted to the BBC last year that “we sell the hardware at our cost, so it is break-even on the hardware.”

And then there’s Amazon Prime, which offers customers free two-day shipping for a one-time annual fee of $79 and is another loss leader affecting fourth-quarter estimates. Amazon is characteristically hush-hush about its profits (or lack of them) from this program and won’t even disclose how many customers are signed up for the service.

But the number of Amazon Prime customers is growing. According to a recent survey of 300 Amazon customers by Consumer Intelligence Research Partners (CIRP), Prime had 16.7 million members at the end of September, or 40 percent of Amazon’s customers, up from 9.7 million the year before.

“We estimate that Amazon Prime customers spend approximately $1,340 per year, compared to $708 per year for non-Amazon Prime customers, and account for 56 percent of U.S. product sales,” said CIRP partner and co-founder Josh Lowitz. “They do so because Amazon Prime customers buy more than 50 percent more frequently than non-Amazon Prime customers, and they buy more expensive items.” That means that the shipping expenses Amazon incurs for these customers, which by all estimates far exceed the annual subscription fee, has an outsized impact on the e-tailer’s bottom line. In other words, the more items Amazon sells to Prime members, the more money Amazon loses.

It’s those types of skewed profit-and-loss models, routine aspects of Amazon’s business plan, that led Slate blogger Matthew Yglesias to describe the company earlier this year as “a charitable organization being run by elements of the investment community for the benefit of consumers.”

Yglesias continues: “The shareholders put up the equity, and instead of owning a claim on a steady stream of fat profits, they get a claim on a mighty engine of consumer surplus. Amazon sells things to people at prices that seem impossible because it actually is impossible to make money that way.”

Investors are buoyed by analyst reports that promise considerable earnings growth for Amazon after 2014, to as much as $10.13 per share in 2016.

However, shareholders hoping to get some of this money in the form of dividends will be disappointed. Amazon has no plans to divide its profits – should they ever materialize – with investors anytime soon.

“We intend to retain all future earnings to finance future growth and, therefore, do not anticipate paying any cash dividends in the foreseeable future,” the company says on its investor relations Web page.

That may be a moot point anyway. Amazon faces significant headwinds that could throw the lofty income-growth estimates well off course.

For one thing, Amazon’s ability to make a profit depends largely on its delivery costs. A huge portion of its expenses – nearly 9 percent of net sales – are tied up in shipping; that comes to about $5.5 billion in the 12 months preceding Sept. 30.

“We expect our net cost of shipping to continue to increase to the extent our customers accept and use our shipping offers at an increasing rate,” Amazon said in its annual report last year.

But this doesn’t account for the rate increases coming next year from Amazon’s shippers. On Jan. 26, the U.S. Postal Service will start charging noticeably more for the small Amazon packages it typically carries. For example, a one-pound box will cost 6.3 percent more to ship.

Similarly, United Parcel Service Inc. (NYSE:UPS) will increase North American shipping rates by an average of 4.9 percent next year while FedEx Corporation (NYSE:FDX) plans to increase prices by 3.9 percent.

These higher shipping costs, which analysts have apparently ignored in their earnings calculations, could amount to a hit of hundreds of millions of dollars to Amazon’s bottom line. If delivery expenses go up by about 5 percent, Amazon would be paying about $275 million more in 2014 than it shelled out this year. That alone would absorb a major portion of the $336 million that analysts estimate Amazon will make next year.

The company offsets some of its shipping expenses with revenue generated from what it charges third-party sellers that use its Fulfillment By Amazon (FBA) service. But it’s unclear how next year’s higher shipping costs will be passed on to fulfillment customers, or how these higher costs will affect the company’s fulfillment business.

Meanwhile, competing online retailers aren’t standing idly by as Amazon attempts to dominate the e-commerce world with its "revenue now, profits later" strategy. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (NYSE:WMT), in particular, is making online sales a high priority moving forward. The world’s largest retailer recently began offering same-day-delivery services in select U.S. cities, including San Francisco and Philadelphia, and in an investors presentation in October, Wal-Mart cited increased e-commerce business as one of the reasons for its 3.3 percent year-over-year net sales gain in the third quarter ended Oct. 31.

Most analysts believe that Wal-Mart’s online sales are growing at about a 30 percent clip per quarter. By contrast, Amazon’s quarterly revenue growth is only about 20 percent. And Wal-Mart has something Amazon doesn’t have (yet): brick-and-mortar stores from which customers can pick up the items they pre-order online.

Other large online merchants are also gaining ground – especially Google Shopping, which is enjoying annual sales growth of about 90 percent, according to ChannelAdvisor, the e-commerce optimization company. Google’s gains are thanks largely to the fact that third-party sellers pay only for the search advertisement, vs. the pricier commissions that Amazon takes as its cut.

Another rival on the horizon for Amazon is China’s Alibaba, which already offers e-commerce services for hundreds of companies and plans to make a big push for a much larger presence in global fulfillment and third-party sales.

And even as Amazon faces more pressure from other online companies, brick-and-mortar retailers could win back a bit of the price advantage that they ceded to Amazon in recent years.

Since Amazon opened its website in 1994, the e-tailer has avoided paying local sales tax in states where it didn’t have a physical presence, such as a warehouse. But now many states are demanding that Amazon charge sales tax for its products, and although Amazon has tried to fight this in the courts, it has had no victories.

The Senate has already passed a bill requiring that online retailers collect sales tax, but the House version of the bill has thus far failed to make headway. It’s virtually impossible for local retailers to compete with Amazon’s heavily discounted prices, but sales tax parity will at least give them a slightly more level playing field.

Amazon is a bit of an anomaly among e-businesses, as Daily Beast’s Daniel Gross pointed out recently: A typical Internet-based company, like Netflix or a company that makes iPad apps, can add customers without any additional cost. “It costs roughly the same to distribute 1,000 apps as it does to distribute 1 million apps,” Gross wrote.

But Amazon has to expand its physical operations in line with its sales growth. For example, Amazon added 8 million square feet of physical space in the third quarter this year – mostly in warehouses. It hires thousands of seasonal temporary workers to help pack and ship products from these facilities.

To fund some of these investments, Amazon has taken on nearly $3 billion in long-term debt and its interest expense in the third quarter nearly doubled from the same period in the year before. Those kinds of increases in costs will only make profits more elusive.

Investor patience with Amazon – and at the rate its stock is climbing, it might better be termed investor recklessness – is all the more perplexing when the record of other 20-year-old companies is taken into account. Virtually none have been given a free ride by the stock market if they failed to produce profits after a couple of decades in business.

Gross points out, for example, that chipmaker Intel was founded in 1968 and had a 16 percent profit margin in 1988. And Wal-Mart, which has never had a losing quarter in its history, had annual net profit of $2.4 billion by its 20th anniversary.

Amazon declined to comment for this story, but 59-year-old CEO Bezos is never short on words to describe his company and his vision.

“Invention comes in many forms and at many scales. The most radical and transformative of inventions are often those that empower others to unleash their creativity – to pursue their dreams,” he wrote in his letter to shareholders in April. “These innovative, large-scale platforms are not zero-sum; hey create win-win situations and create significant value for developers, entrepreneurs, customers, authors and readers.”

Missing from his list of winners are shareholders, who have been funding perhaps the longest-running equity bubble ever for a technology company. Enough said?

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the Kindle Fire as an e-reader. It's an LCD tablet.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.