‘American Ninja Warrior’ Season 8’s Biggest Obstacle: Compensation For The Athletes

When CircusTrix CEO Case Lawrence was looking for a name to help promote his company's latest extreme obstacle course facility in September, he naturally thought big. But maybe too big — the local New Orleans NBA player he wanted to help him create some buzz came with a hefty $100,000 price tag.

Enter Plan B: Since his Palo Alto-based company builds recreation parks inspired by NBC's "American Ninja Warrior," Lawrence instead turned to Kevin Bull, one of the show's most recognizable contestants. The facility’s grand opening proved Lawrence made the right move.

“There was a line a half mile out the door of people and kids waiting to meet him,” Lawrence told International Business Times.

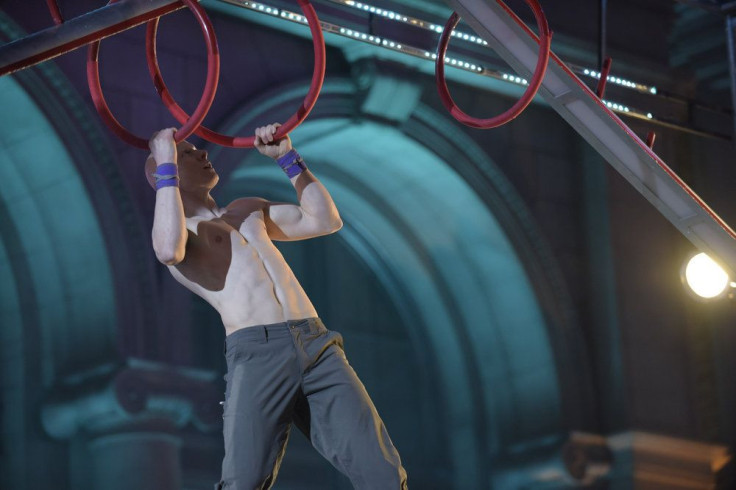

To the casual viewer, "American Ninja Warrior," which returns Wednesday for Season 8, is just a wacky game show. But its seemingly impossible obstacle courses, laced with 14-foot walls, treacherous trampolines and painfully difficult hanging challenges, are no joke. Navigating the difficult courses requires the skill and training usually reserved for professional athletes.

The success of the sports entertainment series, which has become one of the most popular summer TV shows, depends on contestants who view the competition as a true sport. Most only do it for the love of the game. The only real compensation offered in exchange for the high level of competition is the million-dollar prize reserved for those who complete all four stages of the show’s Las Vegas finals course, but that's happened only once in seven seasons. Without a guaranteed paycheck for competing, some athletes are finding other, creative ways to capitalize on their “Ninja” success.

“Being a ‘Ninja Warrior’ takes up a lot of time and energy to prepare for the show every year. It makes it hard to hold a regular job, and the only way to make a living off of it is to win, but that doesn’t happen every year,” Bull, a two-time Las Vegas finalist on the show, told IBT. “There are a lot of us trying to make this more of a full-time thing, and a lot of people have been struggling to do that.”

Bull recently signed an endorsement deal with CircusTrix to train on their courses, be the face of the company in radio and TV ads, and provide his “Ninja” expertise to the company’s engineers — the “Ninja” equivalent of Bull getting his own line of sneakers. The deal, worth between $2,000 and $4,000 a month, is a far cry from the million-dollar paydays scored by some traditional star athletes. But it's a welcome start for a community of athletes still figuring out how to profit from its labor.

“I think it is only the beginning,” Lawrence said. “There is no real established market [for ‘Ninja’ athletes] or understanding of that market, but the value and the name recognition is there. It is so underrated and undervalued right now.”

Although Bull’s deal is the first of its kind for a “Ninja” athlete, he is not the first contestant from the show to cash in on his or her fame from the show. In 2014, Kacy Catanzaro became the first female “Ninja” to complete every obstacle in a regional finals course. Almost overnight, Catanzaro became the show’s most famous athlete, as the gender-centric accomplishment made for perfect fodder for daytime talk shows and nightly news kickers.

A couple of months after the 2014 season finale, Catanzaro appeared in a new ad for Fairfield Inn & Suites, a chain owned by hotel company Marriott. The campaign featured the then-24-year-old athlete going from a gym to one of Fairfield’s hotels, using objects in the lobby as additional obstacles for her “Ninja”-style training.

Catanzaro's commercial was the first true example of the athletes’ market power, but she is not alone.

“I’ve had a lot of good things come from the show,” said “Ninja” athlete Joe “The Weatherman” Moravsky. “I’ve done private and public events, school visits, field days or graduation speeches — there are so many things that I’ve been a part of, which is really cool, and I’ve been making money that way.”

Moravsky’s nickname comes from his meteorology training in college. He now works as an actual meteorologist for News 12 in his home state of Connecticut. His “Ninja” fame has only helped his television news career, he said.

“Of course, being on News 12 and ‘Ninja Warrior’ at the same time — the notoriety helps,” Moravsky said. “It helps build my name up even more.”

For three straight years, Moravsky, who in 2014 rescheduled his wedding to compete on the show, has come within a few obstacles of “American Ninja Warrior” glory. He has reached Stage 3 of the show’s Las Vegas finals for three consecutive seasons, an unprecedented level of consistency among the show’s top athletes. However, the only payday comes from actually winning.

Rock climber Geoff Britten learned that the hard way. In the Season 7 finale, Colorado rock climber Isaac Caldiero and Britten both conquered the previously untamable Stage 3 to force a showdown at Stage 4's daunting rope climb. Britten went first, completing the 75-foot climb in just under 30 seconds and thrilling fans as the first athlete to beat the “Mt. Midoriyama” course. However, Caldiero followed Britten up with an even faster (by 3 seconds) effort to claim the title of “American Ninja Warrior” and the prize money. Britten, on the other hand, received nothing.

The show has made some changes to address the controversy that erupted in the wake of Britten’s finals finish. Now if multiple athletes beat the finals course, they split the money. Additionally, the show has added smaller payouts — ranging from $1,000 to $5,000 — for athletes who come in first, second or third in the regional finals courses.

In that respect, the show operates like most game shows or reality shows, paying for the athletes' travel expenses and distributing prize money. But while the show’s ratings continue to soar, NBC has pivoted to capitalize on its athletes’ individual brands in a way most game shows do not. The show has created spinoffs, like “Team Ninja Warrior” and “U.S.A. vs. the World,” using all-star teams comprising fan favorite athletes. It also has brand partnership deals with companies like Lego, which has created a promo video for a new Season 8 obstacle using the likeness of some of the show’s biggest names, including Bull, in Lego form. Based on the agreements the athletes sign, the show has the right to use the athletes’ likenesses without compensation.

Save for the occasional winning streak, a la Ken Jennings on “Jeopardy,” most game show contestants disappear after a loss. The way “Ninja” athletes return year in and year out — via casting decisions based on annual audition videos — decidedly departs from that pattern. The top two dozen or so athletes constitute an unofficial recurring cast, but because of the “game show” distinction, they are not covered by screen acting unions like the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, and there is no established model for compensation.

"American Ninja Warrior" is not totally alone in how it rewards its contestants. The long-running MTV reality competition "The Challenge," which features participants divided into teams competing in physical challenges, awards compensation primarily in incremental amounts of prize money as the show goes on. "The Challenge" does give its cast a small base fee in the ballpark of $4,000, something "Ninja Warrior" does not do. However, unlike in "The Challenge" or most other shows, for athletes on "American Ninja Warrior" to have a realistic shot at the prize money they must put in countless hours of training outside of the show. That intense commitment would seem to warrant a different compensation structure.

One area where a compromise could seemingly be made is sponsorship. If athletes could sport sponsored clothes or gear on the show, it could open doors for many of the more prominent contestants to benefit. But the show is touchy about allowing notable brands to have exposure on the air in a way that could conflict with their advertising deals.

“I have some sponsors, but the problem is, the show is very strict with what logos can be on the show,” Moravsky said. “I’ve gotten away with wearing my shoes because of how small everything is. But it doesn’t get me anywhere close in terms of a career or endorsements where I could live off of it.”

Likewise, Bull is not confident he will be able to represent CircusTrix on the show.

“I understand why the situation is the way it is for us,” Bull said. “We are kind of at the forefront of a new thing here. Obstacle course racing is new and getting very popular, but there are very few companies who have recognized the potential of us as athletes to draw a crowd and build a following.”

Unlike professional sports leagues, which need to offer top athletes competitive salaries to retain the talent to compete with other teams, “American Ninja Warrior” is the only platform for these athletes to showcase their skills. NBC seemingly has all the cards.

“Right now the biggest player is NBC. The economics of that is that there is no one for them to compete with,” Bull explained. “There are many, many 'Ninjas' and relatively few companies that are recognizing the benefits of our brand of athleticism.”

NBC declined to comment for this story.

While some athletes are frustrated, fighting for change poses an additional dilemma.

“It would be nice to get that compensation, but we do not want to do anything that would hurt the show for fans or stop the growth of the show,” Bull said. “The show has raised awareness about the sport, which we want.”

It would likely require the show’s biggest athletes to stand up together to force NBC’s hand, but with each year’s casting in doubt, that is an intimidating proposition.

“Our collective voice is so much greater,” Moravsky said. “Everyone is very scared to take that leap and talk to the executives and say, ‘We would like to discuss our futures. We’ve done a lot for the show, you’ve done a lot for us, and we could all benefit more.’”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.