Amid Zika Virus Fears, Doctors Recall Terror Of 1960s Rubella Scourge

The early part of the 1960s was a particularly harrowing time for a woman to become pregnant. From 1962 to 1965, a virus of global pandemic proportions was wreaking havoc on fetuses, causing miscarriages and birth defects, and although work on a vaccine was underway, it would not become commercially available until 1969.

The virus was rubella, and the terror it caused in the United States has largely faded from public memory. But Louis Cooper and Stanley Plotkin — doctors who were on the front lines of the epidemic and who both worked to develop vaccines for the virus — have not forgotten. In interviews, they recounted the uncertainty, fear and agonizing choices pregnant women faced during those years. The scenario is one to which a spreading outbreak of Zika virus in the Americas is starting to bear eerie resemblance, in a sign that the U.S. may not be so removed as it thinks from the scourge of infectious disease.

“There was a lot of prayer,” recalled Cooper, who during the 1960s was an associate professor of pediatrics at New York University Medical Center and the director of the Rubella Project, which for decades supported and cared for some 1,000 children disabled by rubella. “That was all women had access to. And sometimes that worked out OK, and sometimes that didn’t.”

During the rubella epidemic of the 1960s, 20,000 babies were born with congenital rubella syndrome — which can cause deafness, blindness, heart conditions, intellectual impairment and a host of other severe disabilities — as a result of their mothers contracting the rubella virus during pregnancy. Women who are infected during their first trimester have up to an 85 percent chance of giving birth to a baby with the syndrome. From 1962 to 1965, rubella led to 11,250 abortions and miscarriages, as well as the deaths of 2,100 newborns.

To find out if they had the virus, pregnant women during those years who lived in or near New York City went to see Cooper. Those in Philadelphia went to Plotkin, who at the time was a virological researcher working on a rubella vaccine at the Wistar Institute, a biomedical research center. It was the only place women could go in Philadelphia to get diagnosed.

The diagnosis involved drawing and testing blood, a process that took about 10 days, Cooper said. The doctors hoped to determine not only if the mother-to-be had been infected, but also when. If it was before pregnancy, the fetus would be safe from congenital rubella syndrome. If it was during, the risk was much, much higher. But the answer was not always clear.

“Depending on the timing, sometimes we could be quite successful and say, ‘You’ve not had rubella in the past few weeks or months,’ and that’d be a tremendous relief,” Cooper recalled. Other times, doctors could not tell, and determining the danger to a fetus became a “guessing game,” he said. “What we tried to do was give women the best information we had, and our best estimates of those risks.”

From there, what women did was not just a personal matter. It was a political and socioeconomic one, too.

Some women cried upon hearing him say the words, “There’s a high risk that the fetus would be abnormal,” Plotkin remembered. “I certainly had many anguished conversations with women who had to make a decision about whether to have an abortion or not.” But Plotkin was only the bearer of test results, good or bad. Seeking an abortion — if they could even obtain one — was up to the women, their families and their doctors, he said.

Up until the mid-1960s, 44 states banned abortion except in situations that endangered the mother’s life. For the most part, the procedure was not available to women who were not wealthy or white. And some women objected to abortion on personal, philosophic or religious grounds. Those who did give birth to a child who was disabled faced a lifetime of giving care.

“Having a disability, ranging from quote ‘just’ deafness, intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, autism, had profound impact on the child and on the entire family,” Cooper said.

While they sound similar, the circumstances of the Zika virus outbreak more than a half century later differ in significant ways from those of the rubella epidemic.

Scientists have yet to prove, for instance, the Zika virus causes microcephaly, a birth defect where a baby is born with an abnormally small head and is often disabled as a result. Still, they strongly suspect a connection, and evidence continues to mount. By the time the rubella epidemic of the ’60s hit, on the other hand, it had been more than 20 years since an Australian ophthalmologist had begun connecting the dots between rubella infections in mothers and birth defects in their babies.

Rubella also is contagious, passing directly from one person to another with a sneeze or a cough. For Zika, the primary vector is the hardy Aedes mosquito. It can also be transmitted sexually.

The sense of vulnerability and the fear for the unborn, however, is the same.

Officials in Brazil first reported infections of Zika virus in May. In October, doctors there picked up on a jump in cases of babies born with microcephaly; since then they’ve reported 4,000 such babies, up from 150 annually in years prior, as the outbreak has spread across the Americas and beyond. Three dozen countries and territories so far have reported cases of local transmission.

Fear of the virus has spurred panic in the United States where more than a dozen states have diagnosed Zika in travelers returning from countries with the virus. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a steadily growing list of 30 countries and territories it urges pregnant women and those who plan to become pregnant not to visit. Americans are paying attention, with 69 percent of women in a survey conducted in January saying they would cancel travel to those places.

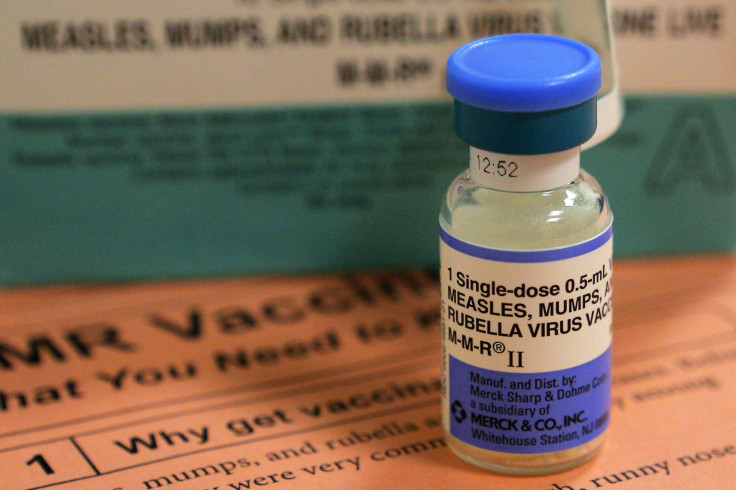

In 1969, the first rubella vaccine was licensed, developed by the microbiologist and pioneering vaccine scientist Maurice Hilleman. Ten years later, an improved vaccine that Plotkin developed replaced that. It was called RA27/3. The RA stood for Rubella, and the number 27 because it was material from the 27th fetus — this one aborted — to which Plotkin had access and from which he ultimately developed the vaccine.

“It was that plentiful,” said Paul Offit, who worked under Plotkin in the 1980s at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and now is the director of the Vaccine Education Center there, as well as the author of a biography of Hilleman.

But, he pointed out, for all the pain and devastation that rubella brought, significant good came of it too.

By 2015, those vaccines had helped eliminate rubella in the Americas. Meanwhile, the surge of children born with disabilities during the rubella epidemic spurred the passage of federal special education legislation — for which Cooper himself advocated — that in 1969 established the Centers and Services for Deaf-Blind Children, which then served as the foundation for future legislation that devoted more resources to people with disabilities. In essence, rubella shaped special education in the U.S. The outbreak also profoundly affected the abortion rights movement and the national push for abortion access.

The rubella experience also had another consequence, perhaps an unintended one.

“Since vaccination started in the early '70s, of course, the disease has gone away,” Plotkin said. “Nobody worries about it anymore.” In Offit’s words, in the United States, “people are complacent.”

But the Zika virus is starting to serve as a chilling reminder the routine vaccines that have become standard for Americans can no longer be taken for granted. No vaccine for Zika exists, and researchers have said it could take up to a decade to bring one to market.

For Cooper, a man who once planned to be a small-town family doctor, rubella changed the course of his life. “I was so profoundly moved,” he said of the struggles he witnessed over decades of working with children disabled by rubella. “I got started down that path and haven’t been able to turn away.” Now 84, he works full time with the Measles & Rubella Initiative, a partnership with the goal of preventing congenital rubella syndrome and childhood deaths from measles.

The lesson Plotkin offered was that vaccines have to be developed against a spate of diseases, even ones that aren’t commercially appealing.

“If we had a vaccine against Zika, we could be protecting women,” he said. Without it, “you have the kind of panic you have now.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.