Analysis-Britain's Shrunken Workforce Hampers COVID Recovery

Britain's economy regained its pre-COVID size late last year, but in one crucial way it has not recovered: there are 400,000 fewer workers than at the start of the pandemic.

This stands in contrast to most other big, rich economies where the labour force has recovered more, and adds to the Bank of England's inflation worries after surging energy prices and other bottlenecks pushed it to a 40-year high.

The central bank fears a tight labour market will limit the economy's growth potential and put fresh upward pressure on wages, making it harder to bring inflation back to its target.

People have dropped out of the workforce not for want of jobs: the number of job vacancies advertised exceeded the number of those looking for work for the first time on record this year and the unemployment rate is the lowest since the 1970s.

Instead, Britain has seen a sharp rise in people reporting long-term sickness - potentially due to the after-effects of high rates of COVID - as well as an exodus of older workers and more full-time study by the young.

The Bank of England is not sure any of these factors will turn around soon. And with the pool of European Union workers no longer readily available after Brexit, labour shortages risk trapping Britain in a stagflation rut.

Before the pandemic, Britain enjoyed steady labour force growth and high rates of participation.

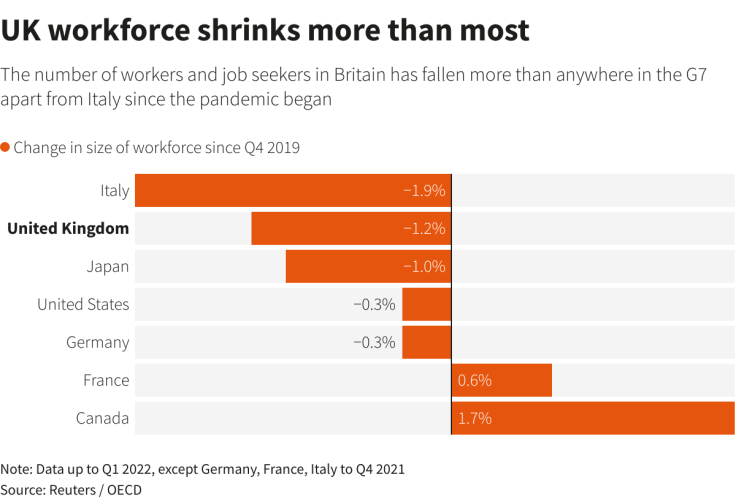

The number of people employed or looking for work in Britain was 34.2 million in the fourth quarter of 2019, but by the first quarter of this year it had fallen to 33.8 million.

Britain stands out here. According to OECD data, across the Group of Seven countries only Italy has seen a bigger percentage drop in the share of those aged 15-64 active in its workforce. Inactivity among the working-age population has increased in Britain by a higher margin than any of its peers.

The decline in Britain's workforce is also the longest since the early 1990s, when a recession caused unemployment to soar and some people gave up looking for work.

"The persistence and scale of this drop has been a surprise to us," BoE Governor Andrew Bailey told lawmakers earlier this month as he sought to explain why inflation is forecast to be stickier in Britain than elsewhere.

(GRAPHIC-UK workforce shrinks more than most in G7:

)

SICKER BRITS

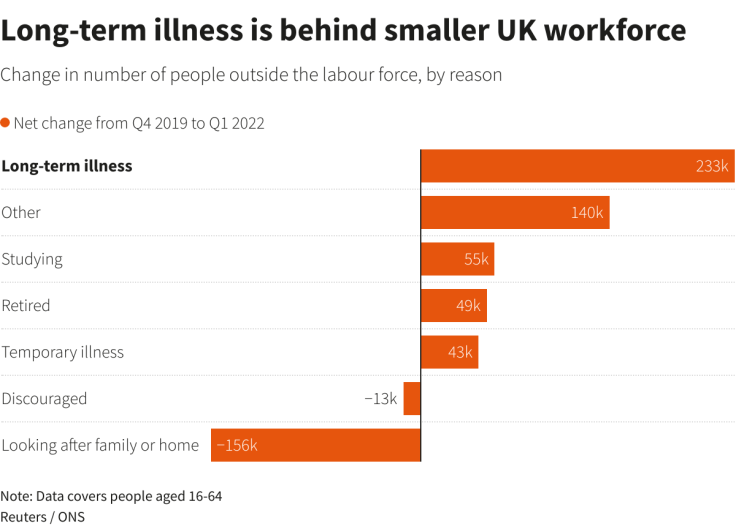

Some 233,000 people left the labour market because of long-term sickness between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, around two thirds of the total outflow. Early retirement accounted for 49,000 and full-time study for 55,000 of the departures.

One category which has seen a big fall is "looking after family/home", with 156,000 fewer people citing as a reason for leaving the workforce than in late 2019.

Hannah Slaughter, an economist at the Resolution Foundation, said this could reflect how remote working in the pandemic had made it easier to juggle a job with other duties.

(GRAPHIC-Long-term illness is behind smaller UK workforce:

)

LONG COVID TO BLAME?

How much of the increase in long-term sickness is directly due to COVID is hard to pin down.

Around 1.8 million Britons reported in early April that they had COVID symptoms lasting more than a month, with some 346,000 saying they were so bad that they "limited a lot" their day-to-day activities, possibly a reason for those of working age to drop out of the labour market.

Michael Saunders, a BoE policymaker, also suggested in a recent speech that a big rise in waiting times for non-emergency medical care due to pandemic backlogs could have made more Britons too sick to work.

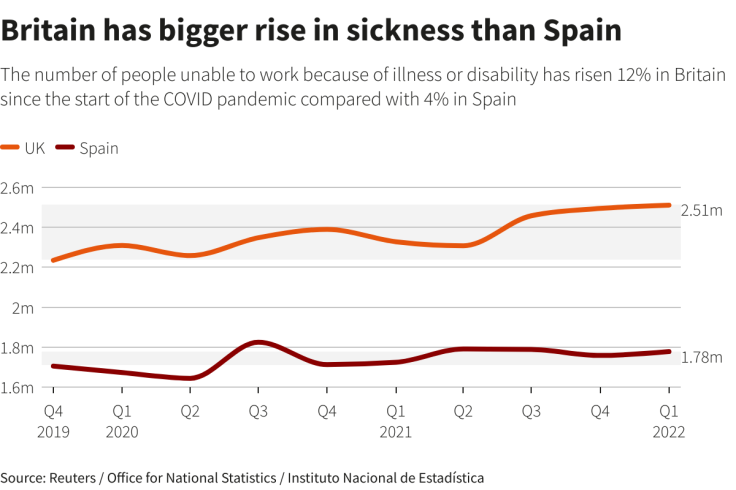

Directly comparable data for other countries is hard to find. Annual EU figures show no consistent trend in the percentage of those unable to work because of sickness or disability between 2019 and 2021, with a sharp fall in France but a rise in Italy, for example.

A comparison with Spain might suggest the severity of the pandemic may have played a role. Spain - which had a 13% lower COVID death rate than Britain - shows a 4% rise in sickness being cited as a reason for staying out of the workforce between late 2019 and early 2022, compared with a 12% increase in Britain.

(GRAPHIC-Britain has bigger rise in sickness than Spain:

)

NO REMISSION

Before Brexit, the strong demand in Britain's labour market - where wages rose by an annual 7% in the first quarter - would encourage more people into work and bring in EU workers where needed.

But over the past two years the number of EU nationals working in Britain has fallen by 211,000 while the number of non-EU nationals rose by 182,000. And hiring from abroad has become tougher as almost all foreign workers now require a visa and filling vacancies quickly with those with the right skills became more challenging.

Saunders said Brexit could be "limiting the extent to which domestic capacity strains and specific skill shortages can be eased through imports and inward migration".

The BoE revised down its expectations for labour force participation in its latest forecasts and sees further falls over the coming years while a looming economic slowdown caused by high inflation is expected to push up unemployment.

In addition, almost all of those citing illness as a reason for not working say they no longer want a job.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.