Analysis: ECB Faces Italian Debt Test As Politics Intervenes

The European Central Bank seems almost certain to face a test of its resolve to rein in excessive bond yields in coming weeks as the euro zone's biggest debtor, Italy, heads for elections that a rightist bloc with a eurosceptic past is expected to win.

The ECB, in an attempt to cushion the impact of rising borrowing costs on Italy and other parts of the euro zone's south, said last week that it would intervene in support of countries whose debt comes under market pressure through no fault of their own.

With the interest premium that creditors demand from Italy rising again and the country nursing a debt outlook downgrade from S&P, expectations of ECB action seem set to grow as the election campaign heats up and investors put a price on radical parties' economic promises.

But the bank has also said it will only buy a country's debt "to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics" and if that country is in compliance with the EU's economic protocols - including one to keep public debt in check.

That sets out the wiggle room that ECB President Christine Lagarde and her governing council colleagues have deliberately left themselves - and suggests that any bets on an early intervention by the bank may misfire.

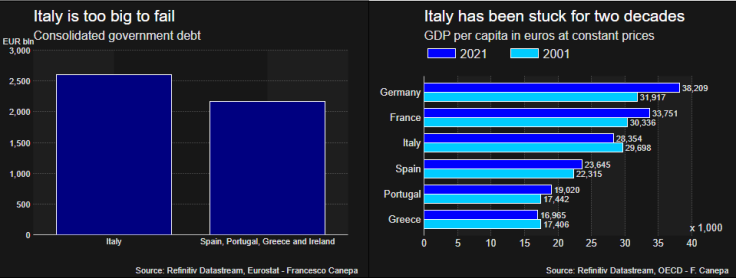

GRAPHIC: Italy is too big to fail and hasn't grown for 20 years (

)

SAFE HANDS NO MORE?

The collapse last week of the government of Mario Draghi - widely viewed at home and abroad as a safe pair of hands - has dampened hopes of an economic turnaround in a country where low growth and high debt have been entrenched for years.

Market nerves have been jangled further by polls that forecast it will be succeeded on Sept. 25 by a conservative bloc that includes one far-right party and two that have promised steep tax cuts and that were openly eurosceptic a few years ago.

Ratings agency S&P Global downgraded its outlook on Monday on worries about the country's ability to meet European Union conditions for securing almost 200 billion euros of pandemic recovery funds, which could prove vital amid a likely recession this winter.

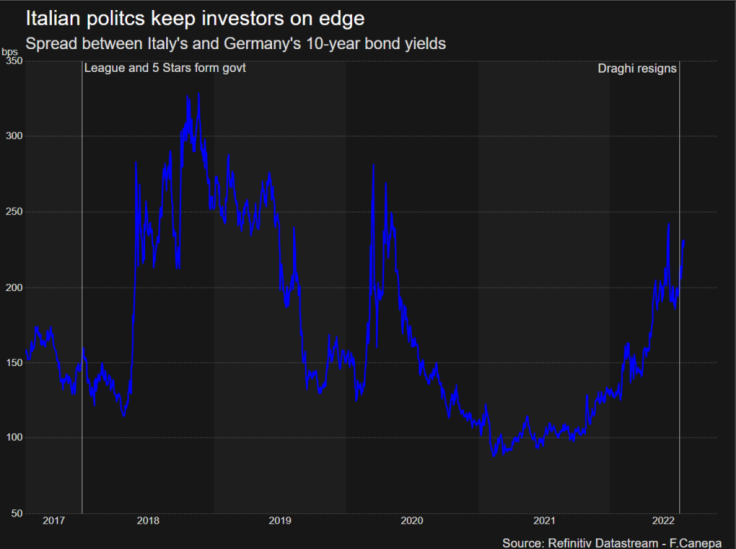

The closely-watched spread between Italian and German 10-year bond yields rose to 248 on Wednesday, just a just a shade below the high hit in June when the ECB accelerated work on the new bond-buying scheme, known as the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI).

Bank of Italy Ignazio Visco has said the current risk premium is much higher than justified and blamed policy uncertainty for that.

But he will need to convince Governing Council colleagues who include Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel, who said TPI should only be used "in exceptional situations" - and any rout on the Italian market driven by electoral pledges could arguably be viewed as self-inflicted damage.

"We suspect the ECB's willingness to intervene in bond markets will be tested sooner rather than later," Jonas Goltermann, an economist at Capital Economics, said.

That test has in a sense already begun, but many analysts don't expect the ECB to step in until the Italian/German spread hits 300 basis points or more.

"I would be very surprised if the ECB intervened below 300," said Jens Eisenschmidt, an economist at Morgan Stanley. "They will want to err on the side of caution in terms of what can be considered justified."

GRAPHIC: Italian politics keep investors on edge (

)

FISCAL GAP

The rightist coalition leading in the polls has yet to unveil its manifesto.

Its two largest parties, Giorgia Meloni's far-right Brothers of Italy and Matteo Salvini's League may have dropped the anti-euro rhetoric of the last decade.

But they have pledged tax cuts that might run into tens of billion euros, without spelling out how these would be offset other than by curtailing access to a basic income scheme, which is likely to cover only a small portion of the fiscal gap.

All parties in the coalition, which also includes Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia, have also been lukewarm about updating property values in Italy's land register, a reform that recommended by the European Commission but that would likely result in higher taxes for millions of people.

That might set Italy on a collision course with the EU - and therefore investors - even before the election.

"Investors would rationally demand higher risk premia, and the ECB should let it be," said Lorenzo Codogno, head of LC Macro Advisers and a former Italian Treasury official.

It did just that when a radical government backed by the League and the Five Star Movement took office in 2018, spooking investors with talk of large deficits and confrontations with Brussels.

Back then Rome backed down. This time the prospect of losing EU funding worth 7.6% of GDP may give its successor government reason enough to do likewise.

In the meantime, the ECB has made clear it retains the final word on any TPI market intervention - a substantial difference from the ECB's previous emergency scheme, known as Outright Monetary Transactions.

Unveiled by Draghi in 2012 when he headed the ECB after his famous pledge to do "whatever it takes" to save the euro, OMT could only be activated if a country requested an official bailout, which meant it was never used after all.

"(TPI) could work as conditions are lighter than with previous programmes and the size is unlimited," said Carsten Brzeski, an economist an ING.

"It might not be a whatever-it-takes but rather a whatever-we-want tool."

(editing by John Stonestreet)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.