Anonymous Hacker Goes Straight: Why Ex-Cybercriminals Have Become Hot Commodities In The Security World

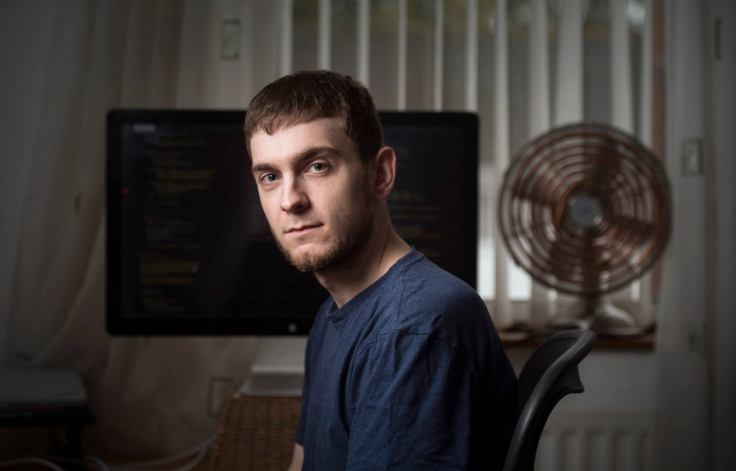

Over a period of 50 days in 2011, Mustafa al-Bassam — then known as Tflow — was one of the six core members of the most notorious hacking collective on the planet. As part of LulzSec — an offshoot of Anonymous — al-Bassam took part in a series of high-profile attacks against Sony Pictures, CBS, the CIA and security company HBGary.

That was before the group’s de facto leader became a snitch for the FBI and al-Bassam was arrested and given a 20-month suspended sentence in Britain. Four years later the former Anonymous hacker is looking to put his past behind him by completing a computer science degree and joining a payments and cybersecurity company as a security adviser and to work on a new blockchain project.

While al-Bassam admits his notorious past has opened some career doors, not everyone in the industry agrees with giving ex-hackers a second chance, believing that the risks are just too high and al-Bassam’s employers are simply playing on his notoriety to get more media coverage.

So what are the risks involved in hiring ex-hackers who are looking to go straight?

“The core of my argument against [hiring ex-hackers] is the risk isn’t worth the return,” Lawrence Munro of Trustwave, a leader in managed security services, told International Business Times. The security expert says convincing clients to let ex-hackers have access to their sensitive data is “a difficult kind of conversation to have” so “for the amount of effort I would need to invest in changing the perceptions of my client base, I just think the return on investment is not worth it.”

For his part, al-Bassam is not too concerned about what other people think of his move — to him, their opinions are inconsequential. However, he is aware his past is unlikely to be forgotten soon: “I think it is going to follow me around but I don’t think it [will] in any sort of massively negative way. Generally my experience has been that it hasn’t affected me very negatively in terms of career prospects,” al-Bassam told IBT. “I would say it has opened more doors than it has closed.”

The cybersecurity industry is experiencing a drought of experienced and well-trained talent, and therefore the prospect of hiring ex-hackers, even those with criminal convictions such as al-Bassam, is being actively considered. A report in 2013 suggested as many as 70 percent of information technology professionals surveyed by online recruiter CWJobs would consider hiring ex-hackers.

Another former hacker who has made the transition to the other side is Cal Leeming, who in 2005, at the age of 19 was arrested after buying more than $1 million worth of goods online with stolen credit cards. Leeming says he understands Munro’s way of thinking when it comes to protecting Trustwave’s business, but only because the company’s clients “simply don’t get how to interact with the security community.”

Leeming says those who advocate for ex-hackers to be barred from the security industry “just don’t get it because they haven’t worked on that side of the fence and for the life of them they can’t put themselves in the mindset of someone who does not give a f---.”

Hiring hackers of course is not a silver bullet. Many hackers simply do not have the necessary technical skills to carry out the type of work needed in the professional world — but this is not a reason to simply abandon them, and what you do get is something more intangible. “Hiring ex-hackers, you are not doing ... for the skill, you are doing it for the mindset,” Leeming said.

Conversely, hiring graduates straight out of college with shiny new cybersecurity or cyberforensics degrees may be equally pointless as they lack the understanding of how the real world works, and specifically how hackers think. “There is an emotion behind it. It is not something you can buy into. It is not something you can just train into.”

Another concern Munro has about appointments like al-Bassam’s is that they are done simply for the optics saying companies are looking to use the notoriety of people like the former LulzSec hacker to create a “media effect” to suggest these people have a “deeper understanding of the issues than the people who have stayed on the right side of the law, which isn’t necessarily true.”

Leeming agrees with Munro on this point: “I do think [Secure Trading] might have taken advantage of Mustafa there, which I don’t feel is right.” For its part Secure Trading says it is delighted to have attracted al-Bassam to the company “to use his skills and create technology to help make the world of e-commerce safer for thousands of customers.”

Munro suggests businesses look at the policies of organizations like the National Security Agency, GCHQ and police forces to decide whether they should hire these convicted criminals. However this suggestion falls down when you look at Leeming, who has carried out security training for the likes of Britain’s National Crime Agency, Ministry of Defense and police agencies.

Leeming was first arrested for hacking at the age of 13 when he was buying groceries with stolen credit cards after his mother spent her money on drugs rather than food. He also turned to drugs a teenager, and changed his ways only when he served a 15-month prison sentence when he was 19.

“I know just how important rehabilitation is,” Leeming said. “I have been there and I’ve seen it. Unless we change our mentality where we are no longer punishing people who make a mistake which may or may not have been their fault, we’re not going to get anywhere, we are just demonizing people, we are just making more criminals.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.