Apprenticeships In America: Four Ways To Get The Country To Take Them Seriously

With the midterm elections out of the way, the big question in American politics is where might the bitterly divided Democrats and Republicans be able to cooperate. One of the main contenders is apprenticeships. They have already attracted a fair degree of bipartisan support in recent years, but still have a long way to go to reach their potential.

The US has a proud history of apprenticeship – Benjamin Franklin was an apprentice printer, for example – but this tradition has largely been lost. The American apprenticeship system used to be connected with labour unions, and they declined together in the latter years of the 20th century. Successive pushes to get more people doing four-year college degrees have also made apprenticeships and other alternatives seem inferior.

Where the US has about a half million active apprentices, England has more than 900,000 and Germany has about 1.3m – both about ten times more than the US per head of population. With Germany in particular, it is often argued that apprenticeship skills help manufacturers in the likes of the car industry to stay globally competitive, while acting as a bedrock for smaller companies, or mittelstand.

Young American workers in many equivalent jobs tend to simply be trained while they work. But in recent years, many Democrats and Republicans have become persuaded that having no formal educational component in such training is a problem.

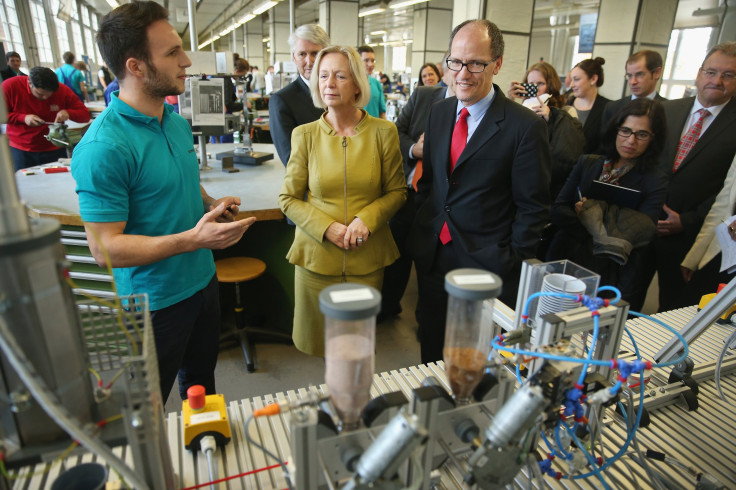

Employers say they are struggling to fill skilled vacancies – particularly in areas like high-tech machine operation and repair. This limits their firms’ growth potential and the economy as a whole. It means fewer stable careers or well paid middle-class jobs. And with automation bringing ever more robots and complex machines to production lines, this skills gap looks an even bigger threat for the future.

Interventions

Following the financial crisis of 2007-08, President Obama identified apprenticeships as a tool for enabling economic recovery. He saw them as a way of creating the skills that would help high-tech manufacturing bounce back, for example, creating a more diversified and robust economy. In his 2012 State of the Union address, he declared:

Tonight, I want to speak about how we move forward, and lay out a blueprint for an economy that’s built to last -– an economy built on American manufacturing, American energy, skills for American workers, and a renewal of American values.

In 2014, he announced a target to double apprenticeships in five years. The White House hosted the first ever “Apprenticeship Summit” for big industry and government players, and Obama helped to drive the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act 2014through Congress. A rare example of both parties coming together, it made funds available to firms to pay a portion of apprentices’ wages.

The government also issued US$175m (£136m) in grant money to directly support 46 apprenticeship programmes in 2015, and persuaded Congress to invest a further $90m in 2016.

Donald Trump, a man famously associated with apprentices for other reasons, has since built on this momentum. In 2017 he signed an executive order to expand apprenticeships, including another $200m of funding. He also put in place a task force to drive the expansion forward.

So far, all this activity has produced a decent upswing in apprenticeship numbers. Yet it still only represents a return to the levels of the early 2000s. Apprenticeships also remain over-concentrated in construction and the military, which account for about half the total.

If the US is going to achieve the expansion that President Trump is seeking, here is what the priorities should be:

1. Reducing stigma

Obama and Trump have certainly made good inroads into reducing the stigma around apprenticeships. Besides his other initiatives, Obama established an annual National Apprenticeship Week that now takes place every November. Trump has loudly backed this initiative, opening this year’s event with a speech where he called a himself a “strong believer” in the apprenticeship model. Earlier this year, the Senate similarly passed a bipartisan resolution recognising September as National Workforce Development Month.

Such statements are not merely rhetoric but an important part of the solution. Apprenticeships in America are still too widely associated with failing to make it into a four-year college programme. The country’s political leaders now need to double down and promote the model as widely as possible.

2. Smarter investments

Without investment from the federal government and Congress, apprenticeships frequently don’t happen. Many firms fear set-up costs like designing a curriculum and getting a programme off the ground.

It can be a particularly good investment when government funding supports clusters of firms to spread costs by offering an apprenticeship programme between them. North Carolina’s NCTAP apprenticeship programme involves ten partner companies in high-tech manufacturing, for example. Future funds could be aimed specifically at supporting these kinds of inter-firm schemes – funding an organisation to oversee a programme, for example.

3. Neglected areas

The flipside of the big concentration in construction and the military is big gaps elsewhere. There are only about 2,500 apprenticeships in healthcare-related occupations, for example, and even fewer in computing.

Widening the scope of apprenticeship in such fast-growing sectors will admittedly be a challenge, because entrants generally have higher-education degrees. But there is a strong case for young people combining learning with practical experience across the board – particularly in a sector like computing, which is changing so rapidly. Federal and state governments should push for industry, colleges and other stakeholders to co-develop apprenticeship programmes for these industries.

4. Allies

America should also be turning to firms and other organisations from Europe to benefit from their expertise in apprenticeship. This could involve the likes of Volkswagen, which runs an apprenticeship programme at its assembly plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee; but also intermediary organisations such as the German American Chambers of Commerce.

It would be useful to invite such organisations to help create a stakeholder group to develop universal apprenticeship standards. The current system is so disparate that it can be difficult to compare skills and competencies, even in the same occupation. This limits the transferability and overall value of an apprenticeship certificate to trainees and employers alike.

Johann Fortwengel is a Lecturer in International Management at King's College London

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article here.