Are Comb Jellyfish Humans’ Oldest Ancestors? Sea Walnut Is ‘Crucial’ To Evolution, Scientists Say

Every now and then, scientists go in and spruce up the ancestral tree of human evolution. The most recent pruning turned up something odd about the origin of life on Earth. Scientists studying the genomes of aquatic life forms found that the comb jelly, a gelatinous marine animal closely related to the jellyfish, is the oldest multicellular animal on our planet – a position previously occupied by sea sponges.

Scientists from the University of Miami and the National Human Genome Research Institute, NHGRI, mapped the first complete genome of a sea walnut, or ctenophores, a type of comb jelly found in the Atlantic Ocean. According to National Geographic, the results of their analysis suggest that comb jellies were the first creatures to evolve over 600 million years ago.

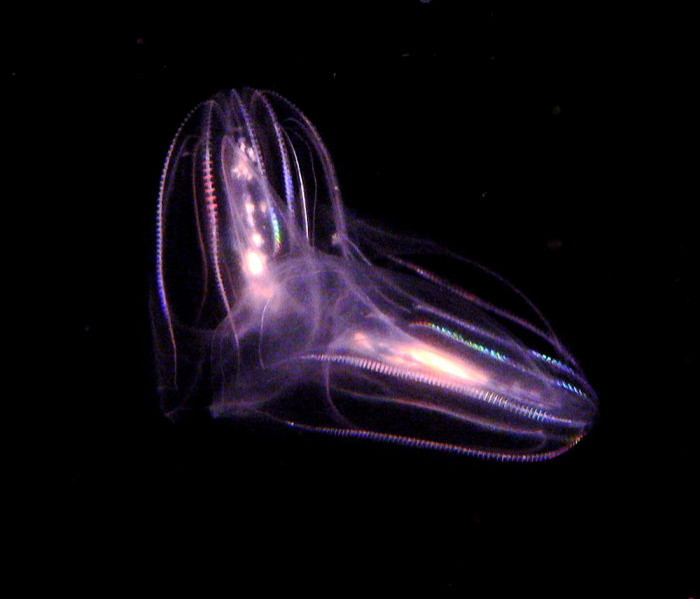

Comb jellyfish live in the oceans worldwide and range in size from just a few millimeters to nearly 5 feet. They are the largest marine animal to move about by cilia, with eight rows of comb plates on their bodies that they use to maneuver about. Comb jellies are delicate, translucent and carnivorous, but unlike their cousin the jellyfish, do not sting.

The new study, published Friday in the journal Science, challenges the long-held view that complex types of cells, like muscles, evolved just once after simple-celled creatures diverged from the rest of the animal kingdom. Until now, genome sequencing was available for four of the five major animal lineages, including sponges and flat invertebrates.

“Having genomic data from the ctenophores is crucial from a comparative genomics perspective, since it allows us to determine what physical and structural features were present in animals early on,” Dr. Andy Baxevanis from NHGRI's Division of Intramural Research and the study’s lead author, said in a statement. “These data also provide us an invaluable window for determining the order of events that led to the incredible diversity that we see in the animal kingdom.”

At the onset of their research, Baxevanis and his team thought they were simply filling in a gap in the genome sequence. But after plugging their data into a computer program that looks for relationships between genome sequences, it turned out that the comb jelly DNA had a different story to tell.

“Our study demonstrates the power of comparative genomics research having an evolutionary point of view, probing the interface of genomics and developmental biology,” co-author Jim Mullikin said in a statement. “The data generated in the course of this study also provide a strong foundation for future work that will undoubtedly lead to novel findings related to the nature of animal biology.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.