Are Energy Companies Leading Shareholders Astray On Future Fossil Fuel Demand?

In the lead-up to the historic United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris in December, it’s not just national governments that have pledged to aim for a sustainable future -- 10 of the largest fossil fuel corporations in the world also have lined up behind the effort. Yet for the oil and gas industry, public acknowledgment of climate change hasn’t changed their rosy predictions of steadily rising demand for carbon-intensive energy.

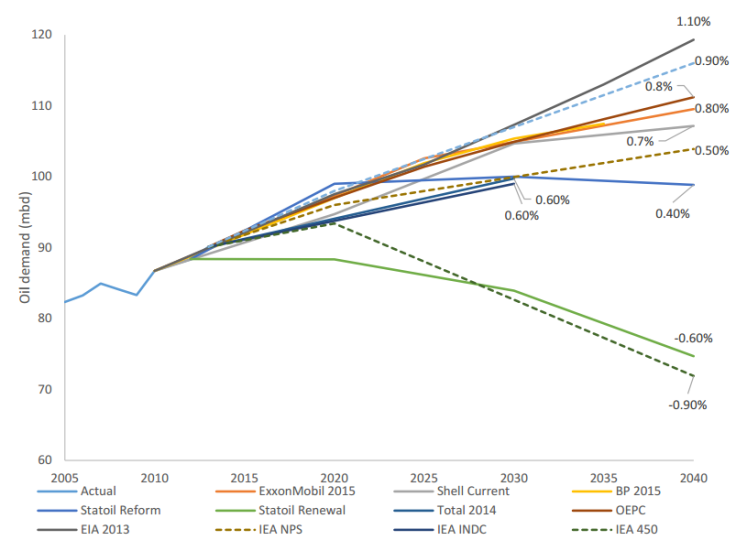

In fact, companies like Exxon Mobil and Shell Oil have continued to project fossil fuel use that would push the world beyond the limits governments have pledged, and beyond what scientists predict the earth can handle. Now some are questioning whether these industry projections truly inform shareholders of future risks.

“They’re planning for a future of no action on climate change, which is not a reasonable assumption,” said Andrew Logan, director of the oil and gas program at the corporate sustainability nonprofit Ceres. “It’s a huge concern from the point of view of shareholders.”

According to a new report from U.K. energy finance group Carbon Tracker, industry projections may not account for possible shifts in fossil fuel demand arising from slower global growth, accelerating renewable technologies and political efforts to reduce emissions.

These projections rely on a straight-line approach to predicting future trends, the report said, while developments like innovation in solar energy could spark more dramatic systemwide transformations.

“They’re using the past to replicate the future,” said Luke Sussams, a co-author of the Carbon Tracker report.

Exxon Mobil, for instance, predicts that oil, gas and coal will predictably make up a smaller portion of world energy use by 2040 as renewable energy captures more of the market. But in aggregate terms, the company still sees demand surging 35 percent in the next 25 years, due largely to continued growth in emerging markets.

But if you factor in the commitments more than 100 nations have made to slash carbon dioxide output, Exxon Mobil easily overshoots predicted demand. The climate-action scenario would see humans emit 576 gigatons of carbon by 2030, a total that itself exceeds the 565-gigaton upper boundary scientists have set for staying below 2 degrees Celsius of warming.

By comparison, however, Exxon Mobil's predictions would see 596 gigatons of carbon emitted by 2030. For Shell Oil, those estimates range as high as 677 gigatons. In short, the companies haven’t treated emissions commitments as any sort of base case scenario.

“These companies aren’t challenging the status quo,” said Sussams.

But it’s not all about political challenges, the report said. Overall energy demand could fall short of expectations if global population fails to meet high-end estimates. Two leading projections of global population growth, for instance, see 900 million fewer people in the world by 2050 than the United Nations estimates.

Economic growth might also lag the sanguine expectations of energy companies. China has become a linchpin in energy companies’ growth predictions, but the country has sagged below growth projections in recent quarters and threatens to cool further.

“They are exceptionally dependent on China demand for oil and diesel,” Logan said. But with new traffic controls and anti-pollution measures to clean the smog-ridden urban areas, Logan said, “that just hasn’t come to pass.”

Renewable energies might also surge beyond fossil fuels faster than predictions have held. In a field where innovation comes in sudden bursts, it’s difficult to predict just when, or whether, electric cars and solar energy will become reliably cheaper than combustion engines and oil.

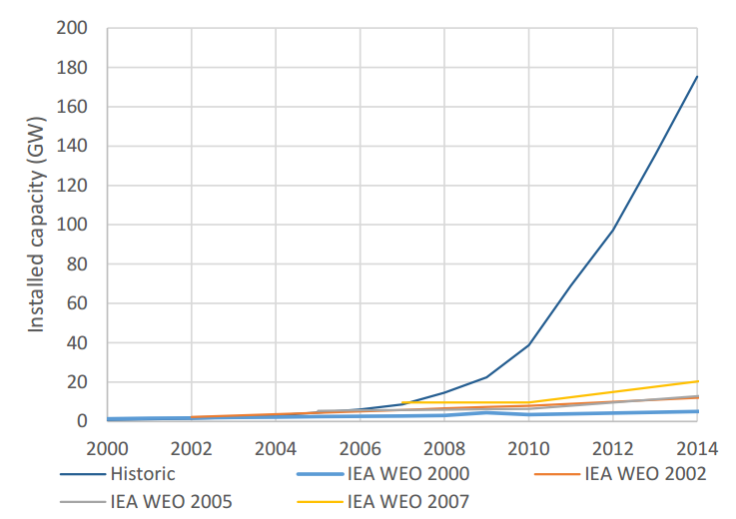

But already, renewable innovations have exceeded expectations. The International Energy Agency, for instance, has continually underestimated the future growth of installed solar panel capacity.

And the cost of electric energy storage -- a crucial factor in renewable energy growth -- has also fallen far faster than industry estimates. Tesla’s release of its Powerwall storage system broke the $350-per-kilowatt price barrier for electricity storage that the broader fossil fuel industry thought wouldn't be reached for seven years.

Then there are the political headwinds to fossil fuel demand. World governments have been preparing for years for the upcoming COP21 climate conference in Paris. Climate negotiators and policy groups have thrown unprecedented weight behind the effort, seen as a last chance at keeping the earth from irreversible climate change.

Some oil companies have picked up on the momentum. Norway’s Statoil and the Anglo-Australian BHP Billiton have both produced scenarios by which the world could stay below 2 degrees Celsius of warming, and other companies have pledged to follow suit with similar models.

Yet no American companies have taken up the challenge.

In recent securities filings, Exxon Mobil has alerted shareholders of risks to future returns, including politically enforced emissions limits and the challenge posed by renewable energies. But in terms of its actions, Logan said, Exxon Mobil still shows an expectation of limitless demand, with recent forays deep into the Arctic and into pricey, carbon-intensive oil sands projects around the world.

Indeed, Exxon Mobil and its peers might have one historical constant on their side: the inability of bickering nations to make firm agreements on climate action.

“It’s reasonable for companies to think this may or may not come to pass because of the history of political inaction on the issue,” Logan said. “But planning on inaction seems like a bad bet.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.