Asteroid Impact Caused Mass Extinction, But Life Returned To Crash Site Quickly

Within a decade of the Chicxulub impactor — usually thought to be a large asteroid, between 6 and 10 miles in diameter — smashing into Earth about 66 million years ago, life had returned to the site of the crash, new research has shown. The monumental incident caused the Cretaceous-Palaeogene mass extinction event, in which 75 percent of all life on Earth, including non-avian dinosaurs, went extinct, and life in other places around the world took as much as 300,000 years to recover.

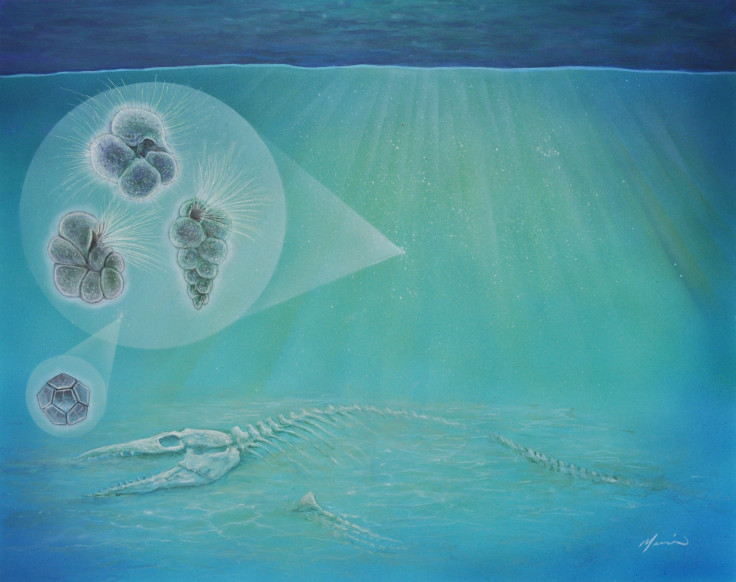

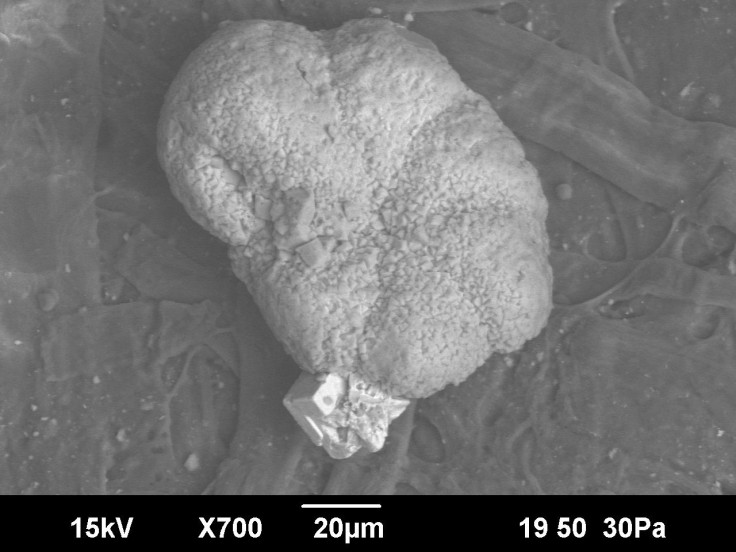

By contrast, a thriving ecosystem already existed within 30,000 years in the sea that had filled up the asteroid’s impact crater, research led by the University of Texas at Austin showed. The finding was based on microfossils — formed by single-celled organisms like algae and plankton — and burrows of larger animals that were discovered in rocks removed from the crater, which is under present-day Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula.

The core drilling was carried out in 2016 as part of a scientific expedition, jointly conducted by the International Ocean Discovery Program and International Continental Drilling Program. The university’s Jackson School of Geoscience was also part of the drilling expedition. The core used for the new study contains over 130 meters (about 430 feet) of material that was deposited in the moments after the impact.

“You can see layering in this core, while in others, they’re generally mixed, meaning that the record of fossils and materials is all churned up, and you can’t resolve tiny time intervals. We have a fossil record here where we’re able to resolve daily, weekly, monthly, yearly changes,” Timothy Bralower, a micropaleontology professor at Pennsylvania State University and coauthor of a paper describing the findings, said in a statement Wednesday.

Analyzing the core provided the scientists evidence for life appearing within two to three years of the impact. Life at the time on the site already included small shrimp or worms or similar animals, evidenced by burrows they left behind. Over the following 30,000 years, there was a blossoming of life as microscopic plants called phytoplankton bloomed, supporting various other organisms both on the seafloor and on the water’s surface.

“Microfossils let you get at this complete community picture of what’s going on. You get a chunk of rock and there’s thousands of microfossils there, so we can look at changes in the population with a really high degree of confidence … and we can use that as kind of a proxy for the larger scale organisms,” Chris Lowery, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) and leader of the research, said in the statement.

The findings are a testimony to the resilience of life, and suggest it can recover from catastrophe (albeit in different forms) in a relatively short period of time, or at least shorter than is commonly thought. They also indicate that local factors play a large role in how much time it takes for life to find its feet again, given how it took 10 times longer for it to flourish again in most other places around Earth.

“We found life in the crater within a few years of impact, which is really fast, surprisingly fast. It shows that there’s not a lot of predictability of recovery in general,” Lowery said.

However, there are aspects of the study that will be scrutinized by the larger scientific community.

Ellen Thomas, a senior research scientist in geology and geophysics at Yale University who was not part of the study, said: “In my opinion, we will see considerable debate on the character, age, sedimentation rate and microfossil content … especially of the speculation that burrowing animals may have returned within years of the impact.”

The paper, titled “Rapid recovery of life at ground zero of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction,” appeared online Wednesday in the journal Nature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.