Austria's Newest Citizens Reclaim Birthright Stolen By The Nazis

Even if they rarely speak German and some have never set foot on Austrian soil, nearly 76 years after the Holocaust, descendants of those forced out of Austria by the Nazis are reclaiming the nationality stolen from their ancestors.

"It was very important for me," says 17-year-old American high school student Maya Hofstetter, who wants to piece together the fragments of her great-grandmother's painful history.

AFP has gathered testimony from new Austrians like Hofstetter who have benefited from a 2019 change in the law which took effect in September, making it possible for Holocaust victims' descendants to gain Austrian citizenship.

The motivations of the applicants -- whose relatives were all Jewish although the law does not concern only Jewish victims -- vary.

From sentimental, to a duty to remember, and for some, a sense of justice, Hofstetter and fellow American Noah Rohrlich, Gal Gershon in Israel, Tomas Diego Haas in Argentina and Robert Anderson in Britain explained in phone and video interviews why they chose to take the step.

Their stories begin with snippets of history passed down through their family trees.

The forced exile of Maya Hofstetter's great-grandmother Stella Rinde Coburn began in August 1939, the year after Austria's annexation by Adolf Hitler's Third Reich.

Gershon's grandfather Eric Otto also left.

"He didn't want to leave Austria. It wasn't his decision," says the 46-year-old sales director for Israel's national carrier, El Al.

"When he was 13 years old in 1938, his parents put him on a ship to Palestine," he says.

Only after World War II did Otto learn that his family had died in the Nazi camps.

Austria had a Jewish population of some 200,000 before Nazi German soldiers marched in to annex the country.

More than 65,000 of them were killed in the Holocaust, with the vast majority of the rest having to flee to survive, settling in locations as far flung as Shanghai and Buenos Aires.

The latter was where Tomas Diego Haas's father ended up after bribing an Argentinian diplomat.

Haas, now 63, practises that most Viennese of professions: he is a psychoanalyst.

Rohrlich's grandfather escaped before the outbreak of the war and got into Harvard in 1946, four years after his parents died in a concentration camp.

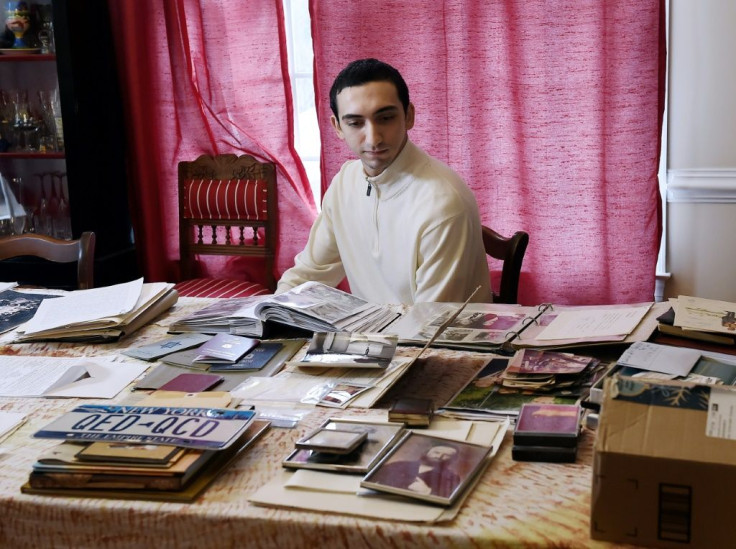

Rohrlich, a 25-year-old resident of the Washington DC area, remembers trying to get memories of Vienna from his grandfather.

"Anytime we asked him about it, we would usually get a one-sentence answer," he says.

A sobering piece of heritage which has reached him is the Gothic-lettered passport of his great-grandparents Egon and Cilly, stamped with the red "J" signifying they were Jews.

Many of those who had to leave were not keen on talking about the experience.

The priority was rather to draw a line under Austria and start afresh elsewhere.

For their descendants, becoming Austrian citizens is often a way of reconnecting with their forebears.

"Now, being an Austrian citizen and an engineer kind of makes me feel closer to him," says Rohrlich, referring to the fact he also shares his grandfather's profession.

Gershon speaks of "a very emotional journey".

"It was closing the story in honour of my grandfather's memory," he says, as well as an attempt to "correct history".

Despite her tender age, Hofstetter is well aware that "the past really does affect the present" and believes that learning about her family's experiences can help her become a "good person".

Her mother Jennifer Alexander, a social scientist for the American government, says that recent political developments in the United States have weighed heavy in her thinking.

"I'm glad my grandparents were not here to see America in the last four or five years. They would have been very upset," she says.

As for Anderson, who speaks of his "delight" when his Austrian paperwork came through, Brexit was a "very important" aspect in his decision to apply for citizenship in a European Union country.

"I feel European, not only British and I was extremely upset when the UK decided to leave the EU," he says, adding that the move was taken "for all the wrong reasons".

The next step for some of the new Austrian citizens is to visit the Alpine country of 8.9 million people.

"I've never been to Austria and it's my true passion to go there and hopefully I will go with my kids," says Gershon.

Hofstetter says she would even "love to live in Austria, to study there."

"I definitely want to connect more with learning the language, the culture," she says.

Rohrlich dreams of finding his grandfather's old apartment.

"Maybe take a tour through Esterhazy Park, where he kept saying it was across from," he says.

"There was also an ice skating rink he was very fond of. I don't know if that's still around."

While few of those whom AFP interviewed expressed a desire to live in Austria, most said they did want to take part in elections and try to find long-lost relations.

Some wonder what their ancestors would make of their decision.

Rohrlich says he thinks his "grandfather would very much have been pleased" and that for him it was self-evident he should take up the opportunity.

Haas, on the other hand, recognises that his father would have had "mixed feelings".

"He had wonderful memories of going to the Wienerwald (Vienna Woods)" and went to the opera several times a week, Haas says.

"But he could not forgive Austria because they took his life away."

Hofstetter, too, thinks her great-grandmother may not have been "very happy" at the prospect of her descendants becoming Austrian.

"I think she would think we are betraying her... Or maybe not betraying her but siding with the people who kicked her out."

It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of descendants of refugees could be eligible for Austrian citizenship.

So far, more than 1,900 have obtained it, mostly from the US, Britain and Israel.

Until now, it has not been possible for them to apply, says Hannah Lessing, the secretary general of Austria's National Fund for victims of the Nazi era.

Chancellor Sebastian Kurz said in a statement to AFP that it was his country's duty to "respond to (the descendants') wishes with humility" in order to right this historic wrong.

"Nothing can take away the pain. The only thing we can do is to ask forgiveness. I am moved to see that this gesture of reconciliation has largely been accepted," he said.

The families interviewed by AFP have been impressed by the warmth extended to them by Austria's current politicians and representatives abroad.

It is as if after three generations Austria is acknowledging the violence of its history.

Germany followed suit in March with an announcement that it was also making it easier for Holocaust victims' descendants to become German.

Austrian historian Oliver Rathkolb calls the move on citizenship "an important signal" which shows that society "is taking the consequences of the Holocaust seriously" over the long term.

Even though several laws mandating the return of stolen goods and property to victims were passed in the immediate post-war period, Austrian society for decades clung to a narrative claiming the country had been the Nazis' "first victim".

It was only after a storm of controversy over the Wehrmacht past of presidential candidate Kurt Waldheim in the 1980s that a more critical appraisal of Austrians' role in the Nazi period gained ground.

However, this did not prevent the far-right Freedom Party (FPOe) -- created in 1956 and initially led by a former Waffen SS officer -- from entering government, first in 1983, then again in 2000-2005 and 2017-2019.

After a long period in which the FPOe rejected the notion of Austrian complicity in Nazi crimes, the party has in recent years become more amenable to attempts at restitution as part of broader efforts to clean up its image.

In Buenos Aires, Haas remembers with some bitterness the "very ugly" reception from one Austrian official when he attempted to apply for citizenship a few years ago, before the new law.

"He was repeating: 'You are the son of an Argentinian', he told me that three times".

Haas felt his father and grandfather's Austrian identity were being denied.

Hannah Lessing is at pains to point out that among Austrians today "that awareness of what was lost is there" and that descendants are welcome to "come back when they want".

"When you look at what Jewish culture contributed in art, science, medicine, culture, intellectual life -- it was an unbelievable richness," she says.

That richness was particularly evident at the turn of the 20th century, with Austria's Jewish community producing such luminaries as writer Stefan Zweig, father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud and composer Arnold Schoenberg.

Hints of the "world of yesterday" described by Zweig in his famous memoir are to be found in the Viennese touches to Anderson's home in the eastern English town of King's Lynn.

Not least among them is a 100-year-old Boesendorfer piano.

Anderson, 77, is descended from the elite of the Austro-Hungarian Empire: his grandfather ran a big oil company before fleeing to London with his family.

Anderson himself went on to become the director of the British Museum in 1992.

He along with others was responsible for the construction of the spectacular Queen Elizabeth II Great Court, designed by Norman Foster and opened by the Queen in 2000.

The other new Austrians cherish traces of their heritage, too.

Haas has a traditional "Loden" jacket he bought on his first visit to Vienna.

Gershon says that while his grandfather "never explained or shared any memories" of his childhood, he did pass on his love of sweet "Marillenknoedel", a sort of apricot dumpling typical of the Wachau valley.

Now he makes them for his children in what he describes as "a little tribute to my grandfather's memory".

"I said 'yes' and he said: 'Well, then you will never understand Freud!'"

Nevertheless, Haas stresses that he had "an Austrian culture and education" and that he "feels at home" in Austria.

"I was Austrian, the only thing is that now, they recognise it," he says.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.