The Benefits That Places Like Dayton, Ohio, Reap By Welcoming Immigrants

The Trump administration’s emphasis on immigration has often stoked partisan political battles. Those debates, as loud as they are, sometimes obscure the fact that immigrants are about 14% of the U.S. population.

Immigrants are adjusting and adapting to life throughout the country and most of them are legal residents or naturalized citizens. As we have explored through our research, this includes newcomers settling in the South, in rural areas and all over the heartland.

The successful incorporation of immigrants into U.S. communities is important not only for newcomers themselves, but for everyone – in terms of avoiding the social and political conflict that can accompany demographic changes.

As scholars studying how immigrants establish lives in these new destinations, our research casts light on national and local policies that support this process, and those that don’t help at all.

A new destination

Consider what’s happening in Dayton, Ohio, a city that, like many Midwestern towns, has struggled with population loss in recent decades.

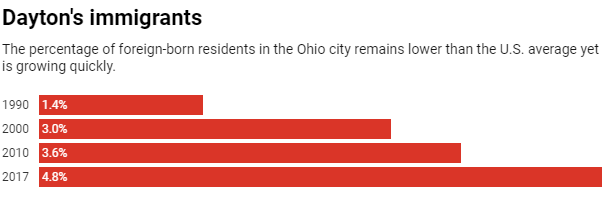

Immigrants began settling there in the 1990s, with most coming from Latin America and Asia. Many of these newcomers, who now account for about 5% of the city’s population, are refugees from places like Uzbekistan, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The local government has embraced the immigrants and the demographic changes they bring through its Welcome Dayton initiative that we have been following as it unfolds. The municipal program, working with a staff of just three people, helps immigrants get jobs, learn to interact with community institutions, build trust with local police and get accustomed to life in a strange land. It even holds an annual soccer tournament for immigrants.

The initiative started with a small group of religious leaders, academics and government officials motivated by moral and humanitarian concerns to help immigrants successfully settle into Dayton.

But there are also practical reasons for cities like Dayton to encourage immigrants to stay, be part of the community and put down roots.

Shrinking no more

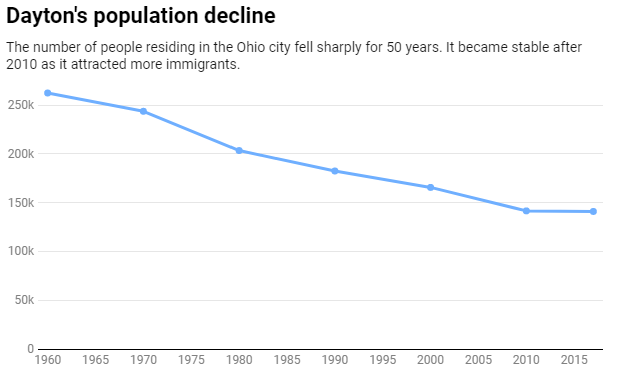

Across America’s so-called Rust Belt, where once buoyant industries have given way to widespread unemployment, populations are shrinking and economies are suffering. Dayton is an example: Its population sank from a peak of 262,300 in 1960 to 141,527 in 2010.

Census data from 2017 indicate that the number of local residents has become stable.

Many signs point to immigrants having made that happen, chief among them that the U.S.-born population has continued to decline. Between 2009 and 2013, it fell by 8.6%, about 13,000 people. During the decade leading up to 2016, the foreign-born population had roughly doubled to about 7,000, according to a Dayton Daily News analysis of census data, making the city home to one of the nation’s fastest-growing immigrant communities.

The city’s economy is benefiting from the newcomers, who are more educated, on average, than its U.S.-born residents. Immigrants also tend to be more entrepreneurial than people who were born here, making them almost twice as likely to start their own business. According to research by Duke University economics professor Jacob L. Vigdor supported by a pro-immigration group, the arrival of immigrants has been a boon for manufacturing jobs and housing markets in many places like Dayton.

We’ve seen this with our own eyes as new businesses have popped up on streets that had only a row of empty storefronts 15 years ago.

The 4.8% share of Dayton residents born in other countries remains below the national average. But that still marks a big change from 2000, when only 3% of the people in Dayton were immigrants.

In our view, these new residents are making a positive difference as they pay taxes, join religious congregations, and become local leaders. In turn, this is reflected in the fact that most city residents say they would be supportive if an immigrant family moved in next door.

Research indicates that Dayton’s experience is pretty common. Cities that welcome immigrants and refugees tend to see benefits like economic growth and a stronger sense of civic pride as urban blight recedes.

Fear and anxiety

Stricter immigration enforcement has changed things across Ohio, like the rest of the country.

In fact, one of the most striking preliminary results of our current survey of Dayton’s immigrant community, which we began in 2017, is their growing fear. Even newcomers who have legal status – which most in Dayton do – fear they could be attacked, detained or deported anyway.

These jitters can make it harder for immigrants to develop connections with their neighbors, as some avoid going out in public to forestall any trouble.

In part, these concerns arise from the increasing frequency of hateful speech and actions. Immigrants we interviewed described encounters with people who hurled racial slurs like “dead Muslim” or “terrorist” or being told to “go back home.” Their children have experienced bullying at school. Posters and pamphlets from white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, which plans to hold a rally in the city, are popping up more.

Other forms of backlash are more subtle, but also send a message of rejection that immigrants hear loud and clear.

Some of this rejection comes from suburbs around Dayton. For example, two state representatives from nearby suburban districts objected to a Dayton Public School Board motion – largely symbolic – that affirmed the district’s commitment to being a “safe and welcoming” place for all students regardless of immigration status, national origin, sexual orientation, race or religion.

In response, Welcome Dayton and other community institutions have taken steps to support the immigrant community in this time of increased division and politicization. There are new efforts around “know-your-rights” trainings, and a rapid response team to accompany immigrants to their legal hearings or care for children left behind after a parent is deported.

Interestingly, more people are volunteering to tutor immigrants in English, and engagement in similar initiatives has increased. As far as we can tell, Dayton as a whole continues to welcome the immigrants who are settling in the city.

Miranda Cady Hallett is an associate professor of Anthropology, University of Dayton. Theo J. Majka is a professor of Sociology, University of Dayton.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the article here.