Better Behavior, Fledgling Population Immunity Behind US Case Decline

The trend line is now unmistakable: the US Covid outbreak is easing, with new cases and hospitalizations down two weeks in a row, even though the overall numbers still remain far higher than prior to the fall-winter surge.

What's behind the slide? Experts say there are many reasons, from a better adherence to masking and distancing measures, to the fact that the holiday period is now well behind us.

Another factor, at least in some areas of the country, is that the virus has already burned through much of the population and is running out of targets -- but easing restrictions too fast could still upset the current equilibrium and trigger a new spike, scientists warn.

Here's what you need to know.

After a summer lull, the US infection rate began to pick up again last fall, when gatherings began to move indoors and people started letting their guards down.

Then came the holiday season: Thanksgiving, Christmas, then New Year's: a coronavirus triple-threat that sent cases soaring as millions of Americans ignored official guidance and visited their families and friends.

The US was clocking a daily case average of more than 250,000 by the second week of January, and more than 130,000 hospitalizations, according to data from the Covid Tracking Project.

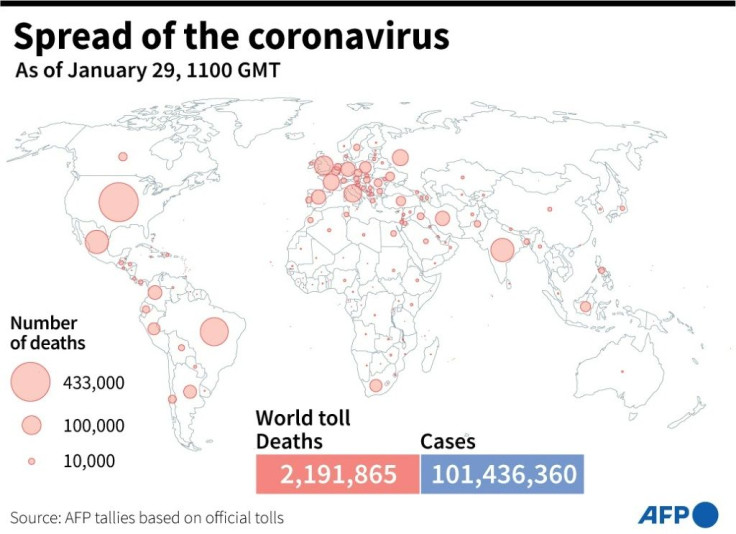

There are still more than 3,000 deaths on average per day, because of the lag time, but overall the metrics are heading in the right direction.

"That holiday travel which the virus was exploiting has kind of dissipated," Amesh Adalja of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security told AFP.

The spread of infectious diseases is innately linked to human behavior.

Natalie Dean, a biostatistics and infectious disease expert at University of Florida, told AFP she saw a "population-level feedback mechanism, such that people respond to rising numbers in their areas."

She cited how Florida, Texas and Arizona quickly turned things around after their summer surges. "Whether through policies or many small behavior changes, the numbers slow," she added.

Brandon Brown, a public health specialist at the University of California, added "there is also less misinformation compared to before, and it's hard to deny the over 400,000 deaths."

But if people respond to rising cases by becoming more cautious, the opposite can also be true when infections decline, warned the experts.

The current number of confirmed cases in the US is around 25 million -- but we know by now the true figure is likely to be much higher, and could be as high as 100 to 125 million people, Stanford professor Jay Bhattacharya told AFP.

We know that natural infection confers a high degree of immunity, at least for a period of time, then you can add the people who have received at least one vaccine dose (which confers partial immunity) -- currently 21 million.

The two figures together get you to around 40 percent of the population of 330 million -- inching towards the goal of 85 percent thrown around for "true herd immunity," but still some way to go.

The vaccinations already delivered to nursing homes is probably responsible for pushing down the hospitalization and death rate, said Adalja.

Jeffrey Shaman, an epidemiologist at Columbia who has been modeling the population immunity question, says that according to his team's calculations, "between 50-70 percent of North Dakota's population has been infected with the virus."

While this is one extreme, Shaman said that between rising national-level population immunity, and current behavior patterns, the outbreak "should be self-limiting at this point."

The problem would be if behaviors changed, breaking this delicate balance, said Shaman and Bhattacharya.

As spring comes, people may start moving around more than they are currently, and more infected people could then come into contact with people who are not immune.

Finally, new variants present "wild cards," whose transmissibility advantage would raise the statistical threshold needed for true population immunity -- and in the case of the South Africa variant, pose a greater reinfection risk.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.