Better Forest Management Won’t End Wildfires, But It Can Reduce The Risks

President Donald Trump’s recent comments blaming forest managers for catastrophic California wildfires have been met with outrage and ridicule from the wildland fire and forestry community. Not only were these remarks insensitive to the humanitarian crisis unfolding in California – they also reflected a muddled understanding of the interactions between wildfire and forest management.

As scientists who study forest policy and community-based collaboration, here is how we understand this relationship.

Fire is a natural hazard

In cases like the Camp Fire in Northern California, where low humidity, dry vegetation, hot temperatures and high winds have created extreme fire conditions, there is little that homeowners, forest landowners or land managers can do to affect fire behavior. Fire is a natural hazard, like earthquakes, tornadoes and hurricanes. It is unique in that it can develop with little warning and last for weeks or even months.

Like other natural hazards, wildfire cannot fully be prevented. However, it is not only possible but urgent to prepare for it, and to get people out of harm’s way when conditions are life-threatening.

It is also increasingly clear that climate change is making these kinds of fires more likely by creating longer fire seasons and hotter and drier conditions. As Toddi Steelman, a prominent fire scientist at Duke University, recently tweeted, “We are only kidding ourselves if we don’t think [a disaster like the Camp Fire] could happen again tomorrow. All the conditions point to more of this in our future.”

Preparing for the inevitable

Despite this reality, there are ways to prepare for fire. During less extreme fire events, actions by homeowners can reduce the risk that their houses will burn down. By clearing brush around homes, changing ventilation systems, keeping roofs and gutters free of leaf litter and moving wood piles, owners can reduce the likelihood that their houses will ignite and create safe spaces for fighters to defend their homes.

Local governments also must continue to improve plans, alert systems and resources for people when it’s time to evacuate. Events in California have shown that time can be extremely limited, and as with other natural disasters, poor and disadvantaged individuals who have limited resources to get to safety will often suffer most. More can be done to prepare to evacuate towns and get information to people rapidly.

Many also have expressed concern about housing growth in places where homes are in close proximity to forestlands that can burn – the area known as the wildland-urban interface. However, many of the most tragic fire events in California, including this year’s fires and those in Napa County in 2017, occurred in urban and suburban areas. Land use planning and improved housing codes, both of which require local initiative, have a role to play in reducing home loss, but a growing number of people will continue to live in areas with significant fire risk in the future.

The role of forest management

Many ecologists say that in some places, forest management – which includes thinning brush and small trees and burning under the right weather conditions – can help reduce unwanted effects when wildfires occur. This is especially true at lower elevations and in drier forests, like the ponderosa pine forests of the Southwest.

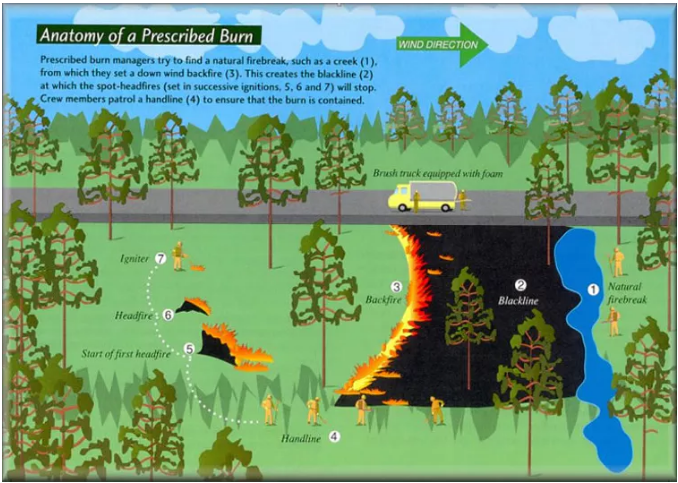

Across the country, forest managers, community-based partners and environmental groups are working together to thin trees and increase use of prescribed burning, in which managers intentionally ignite fires under less extreme conditions. Although it may seem counterintuitive, allowing more natural fire to burn under less extreme conditions, instead of suppressing every blaze, also is important.

But thinning and prescribed fire won’t make a difference in all ecosystems, and there are limitations to land management. For example, the Woolsey Fire in Malibu, which now is almost fully contained but has destroyed 1,500 structures and killed three people, is in non-forested shrub lands, where these techniques are unlikely to make a difference. And in high-elevation forests, many scientists say management activities like thinning are inappropriate because fires in these forests are driven more by weather conditions than fuel loads.

There is also disagreement about the value of thinning, particularly if it is not followed by prescribed fire, for changing fire behavior. And efforts to thin and burn in forests may not have any impact on fire behavior under extreme weather conditions.

Prioritizing the right work

The United States has vast fire-prone forested ecosystems. Federal and state agencies and private forest owners cannot possibly manage them all for fire, nor should they aim to. In our view, the right approach is to make efforts in targeted locations, with an increased focus on reducing fuels near communities and in other key areas such as municipal watersheds.

In our research, we have found that improved policies and partnerships are essential for restoring forest conditions and conducting prescribed fires. Policies that promote collaboration allow local partners to share resources and find agreement about how to tackle complex fire management issues with local support.

It is also important to focus funding investments on priority landscapes. Forest management resources are limited, so it is critical that the federal government, states, counties and community members work together to implement targeted solutions.

Another key point is that most thinning and other fire hazard reduction does not typically yield trees and other forest byproducts with economic value. This makes the work expensive. The most valuable timber in the United States typically is not in places with the highest fire hazard, and more commercial logging is not going to stop fires. A lot of good work has already been planned, but more funding and capacity will be needed to get it done.

Solutions for reducing wildfire risk are not always intuitive. They vary from one location to another, and conditions are ever-changing. In the face of growing risk and unprecedented conditions, everyone involved in fire management must recognize the inherent complexity of responding to fire, and work together with communities, firefighters and land managers to find answers that are tailored to different places.

Courtney Schultz is an Associate Professor of Forest and Natural Resource Policy, Colorado State University and Cassandra Moseley is Sr. Associate Vice President for Research and Research Professor at the University of Oregon.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article here.