Biotechs Increasingly Favor Leaner 'Virtual Startup' Model Amid Public Outcry Over High Drug Prices

SEATTLE -- Ingrid Swanson Pultz's biotech company lacks most of the standard accoutrements. It doesn’t have a lab or an office -- or any employees. Pultz launched PVP Biologics while working as a microbiologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. With half a million dollars in grants and donations, she hires the people she needs on a contractual basis or asks them to join one of the company's advisory boards.

Pultz's company is investigating a potential treatment for celiac disease, and while her approach may seem unconventional, a growing number of founders are embracing the "virtual startup" model as a way to save on the onerous upfront costs of creating a business from scratch.

This break from the standard industry playbook is particularly attractive to entreprenuers and investors at a time when the biotech industry faces greater public scrutiny, and presidential candidates threaten to reel in drug prices. While companies are under no obligation to pass on savings, and drug prices do not necessarily reflect the cost of drug development, virtual biotechs are better positioned to introduce their medicines at lower launch prices if they're so inclined.

“I think anything that can take a chunk of the cost out of the system is a step toward making drugs more affordable, and that's one of the main benefits of this model,” says Bernard Munos, a biotech analyst and consultant at the InnoThink Center for Research in Biomedical Innovation.

It works like this: Most virtual biotechs own the rights to a potential treatment purchased from another company or developed at a university. Once the company has a drug candidate, one or two people can lead a virtual team of consultants and outsource the research to a company that conducts initial tests and develops the medicine to the point where it is ready to enter clinical trials.

Dr. Richard Stead has helped launch between 40 and 50 virtual biotechs over the past 13 years through his company, BioPharma Consulting Services, near Seattle. Despite his long professional history with brick-and-mortar operations -- he was the first physician employed by Amgen in 1988 and later worked for Immunex -- he now professes a particular fondness for virtual companies.

“I don’t think the virtual team is for every company or for every function within a company, but I think it can be more capital-efficient and I think you can get, on average, a higher quality of person and experience in that way,” he says. “I think there’s a real place for it.”

Stead is currently advising Pultz on PVP Biologics. So far, she has hired a toxicologist to help plan animal studies, a consultant who specializes in manufacturing, and Stead, who designs clinical trials. She calls them from her home office each week. When they do meet in person, it’s in a nondescript conference room in the Life Sciences Building.

In the early days of biotech, companies spent millions to build elaborate headquarters with labs and office suites long before any of their products were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Biotech leaders thought companies needed to be fully integrated and able to handle all aspects of researching, developing, commercializing and marketing a potential drug from Day One.

But many of these companies failed to ever produce an FDA-approved treatment. Those that did were often bought by pharmaceutical companies, which unceremoniously disposed of their headquarters anyway. It wasn’t long before this model began to seem inefficient.

“That’s not how companies are started these days,” Chris Rivera, president of the Washington Biotechnology and Biomedical Association, says. “ I think going from ground zero to building infrastructure from Day One is probably kind of a bygone era that we probably won’t see going forward.”

Over the past decade, more biotechs have forgone the luxuries of lab space and full-time employees to operate virtually during the early stages of research. Now many investors even prefer it. Patrick Heron, who oversees life sciences for Seattle-based investment group Frazier Healthcare Partners, says between 30 and 50 percent of the companies he funds begin as virtual endeavors. He estimates that 15 years ago, only 10 percent of companies were virtual.

In September, biotech stocks temporarily dropped following widespread public criticism of Turing Pharmaceutical’s sudden price hike on a prescription medicine and vows by several Democratic presidential candidates to fight skyrocketing drug costs. If that pressure continues, Heron says the industry can expect to see more virtual companies launched on lean budgets.

“If the market continues on its current trend, I think you're going to see more virtual companies and more use of outside resources,” he says.

Munos tends to agree. “If there is a backlash and the prices are ratcheted down, companies that operate on a virtual model will be able to withstand the shock much better than others,” he says.

Already, there are plenty of success stories about companies that went the virtual route. Take, for example, Zafgen. Its founders used a virtual model to take a drug to treat obesity all the way through midstage clinical trials for about $68 million, a sum that Munos says is about one-fifth of what a major pharmaceutical company might spend. In June of 2014, it earned $96 million in an initial public offering. This year, Alexion Pharmaceuticals acquired a virtual company called Synageva BioPharma, which makes rare-disease treatments, for $8.4 billion.

Seattle is well-positioned for this model to take hold. The state is a hive of activity -- 120 new life sciences companies have been launched in Washington this year, bringing the total number of new ventures to over 400 since 2009. “It's been a frenzy, maybe is the right word,” Rivera says.

But at the same time, the city suffers from a lack of available lab space and a dearth of talent. Together, these factors convince many founders and CEOs that a virtual model is the right fit.

“More and more companies are becoming virtual,” Rivera says. “I think most of the startups are starting in that form and fashion now just because it's so darn expensive to put a brick-and-mortar together or find lab space.”

Pultz says her model is a great fit for investors who are more skittish about making a substantial contribution for a large infrastructure project before a drug is even proved. “It’s a way to compensate for the fact that a lot of groups in biotech are more risk-averse than they used to be,” she says.

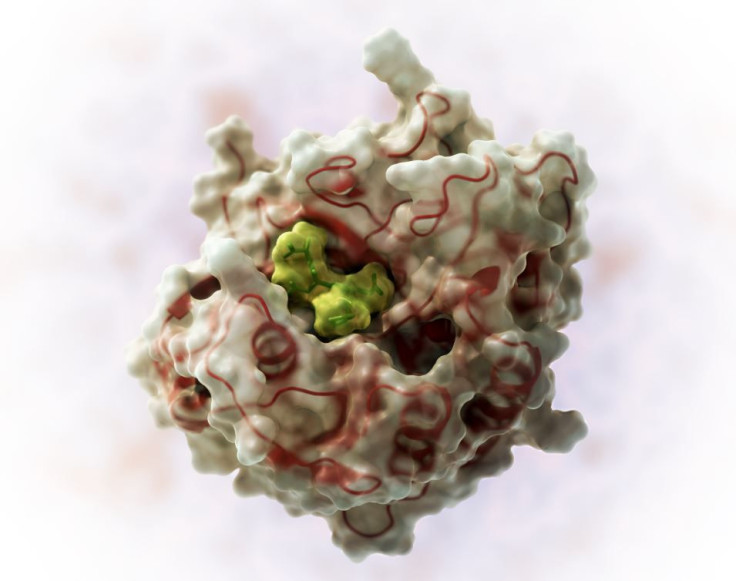

In the crowded university office and lab space she shares with other early-career researchers and graduate students, Pultz is putting the finishing touches on an enzyme called KumaMax that breaks down fragments of gluten that naturally pass through healthy individuals but are known to cause inflammation in the intestines of those with celiac disease.

She says KumaMax breaks down gluten fragments “orders of magnitude better” than enzymes already in clinical trials. Her company, called PVP Biologics (a sly reference to “player versus player,” a phase popular with gamers) has no venture capital -- yet. But when she spins out PVP Biologics from the university in the coming year, KumaMax will be nearly ready to enter trials.

Traditional companies might have had to raise millions in venture capital to engineer an enzyme to such an advanced stage. So far, Pultz has paid for consultants through a $250,000 grant from Washington state's Life Sciences Discovery Fund, which was matched by $250,000 in contributions from private donors. Her salary is paid by the Institute for Protein Design at the university. Heron estimates companies can save between 20 and 30 percent of their costs by starting out virtually as compared with launching traditionally.

Pultz hopes to have KumaMax in clinical trials by 2017. She estimates that the company will need between $20 million to $30 million in venture capital to complete the remaining preclinical work and usher the enzyme through the first two phases of testing. Consultants tell her the cost may balloon to as much as $225 million for the third and final stage.

That sounds like a lot of money. But as she watches other companies raise millions of dollars on the promise of a molecule that has yet to be built in a lab, "it gives me hope that we’ll be able to raise our funding,” she says.

Heron says investing in a virtual company requires something of a paradigm shift for investors, who can be easily dazzled by a company’s corporate headquarters filled with legions of staff scientists.

“Your initial concern is, you’re going to lose the chatter and all of the hallway talk that really drives an organization,” he says. “But as you see the productivity of these teams that operate in a virtual fashion, you sort of get religion that this is a good way to go.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.