Black Coder For Hire: Can Unemployed Programmer Justin Webb Find A Job In Silicon Valley Before Christmas?

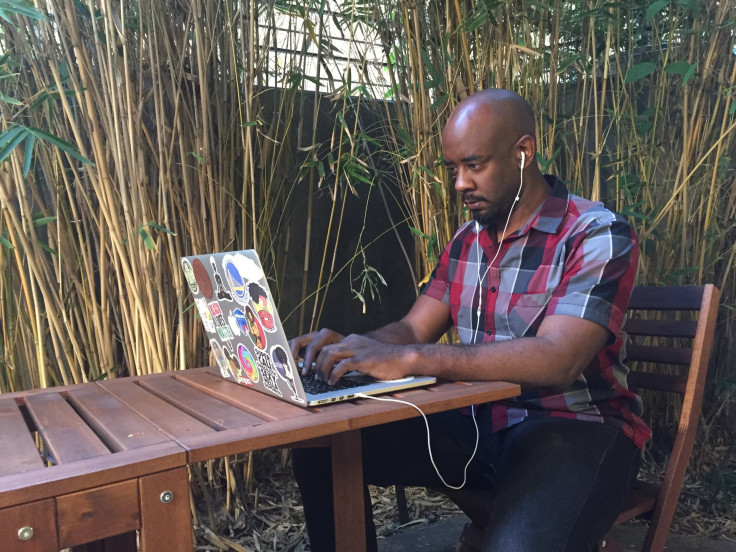

SAN FRANCISCO — Finding a job in tech shouldn’t be this hard for Justin Webb. The 39-year-old software engineer, a father of two, has more than a decade of programming experience and newly minted credentials from a top coding school. And yet here he is, two weeks before Christmas, beating down doors on the streets of San Francisco and trying, to no avail, to land what many assume is plentiful in Silicon Valley: a full-time coding job.

Silicon Valley can be a lotusland for tech pros looking to live the American dream. Established industry giants and startups alike are falling over themselves to offer enormous salaries and perks to new talent. But for all the complaints about the shortage of labor and the need to import workers on H-1B visas, Silicon Valley is still leaving behind solid candidates. Those with imperfect coding skills, lacking a degree from the right schools or simply on the wrong side of 30 can find Silicon Valley’s job market unforgiving.

And then there’s another thing: Justin Webb is black. On the face of it, that should make him a hot commodity in diversity-starved Silicon Valley, an industry that has struggled for years to diversify its ranks to build more inclusive workforces. This failure has been particularly acute in attracting African-Americans, who generally account for 3 percent or less of jobs, depending on the company.

For Webb, it means getting past what he calls the "I didn't know he was black" look he says he gets when he walks in for an interview. “There’s no lack of opportunity, it’s just that once I get in the door it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh,’ ” Webb said, gesturing around with his body, opening his eyes widely. “That reaction.”

Last fall, Webb decided to brush up on his programming skills, so he enrolled in a rigorous program at Hack Reactor, a private coding academy that boasts a job placement rate of 99 percent, with students earning lucrative jobs upon graduation. The average starting salary for a Hack Reactor graduate is $105,000 per year.

He was the only African-American student in a class of 35. Six months later, Webb is also the last one to find a job. With the help of Hack Reactor, International Business Times learned about Webb’s job search in early November and decided to tag along, embedding in his job search to find out what breaking into the tech industry can be like when you aren’t a 20-something young talent, or recently graduated from the likes of Stanford or Berkeley.

With his penchant for plaid shirts and a fedora to cover his bald head, Webb’s style is probably best described as hipster-dad. Like other software engineers, Webb is a low-key individual. His is a deep, calm-mannered, almost monotone voice, but he’s the kind of person who’d rather let his work do the talking for him. While his style is whimsical, his personality is serious, particularly when it comes to finding a job.

“I'm not asking for help. I'm just asking for a shot. Let me get in the door and compete," Webb said in mid-November. “I don't have a degree because I don't have thousands of dollars to pay for that kind of an education. It's not because I'm not capable.”

Self-Taught Coder

Coming by work has never been difficult for Webb, who taught himself how to code using free online tutorials in 2004 when he was working on the Oakland mayoral campaign of Ignacio De La Fuente. From there he fashioned a freelance web design career; at the time it seemed like everyone was looking for web development help. Though Webb has regularly come across six-figure salaries working those jobs, the life of a freelancer is tough.

“You don’t get sick time, you don’t get vacation time. It’s hard to have a social life or a wife or kids or any of that other stuff because the basics aren’t being taken care of,” Webb said. “I got tired of that.”

Since he lacks a college degree, Webb's skills get scrutiny. “When you’re self-taught, like I am, people want to see a portfolio,” Webb said. “I was often working on nondisclosure agreements, contracts or” intranet websites, which are private websites built for internal use by companies. “It was really difficult to face these interviews where I constantly have to explain why I don’t have a portfolio,” he said.

But often, his skin color seems to be another factor that raises flags, Webb said. “I feel like I get a suspicious look. It’s hard to describe, but I feel like they have to take extra care to verify that I’m a good candidate,” said Webb. “That I can do what I say I can do, or that I have done what I say I’ve done.”

Webb figured that if he was going to find full-time work, he needed someone else to vouch for his skills. “I needed a brand or something to augment my position in the market, in addition to teaching me what I didn’t know,” Webb said. “I needed somebody else to co-sign and say, ‘This dude is an engineer, and his résumé is not fake.’ ”

So he decided to cash in his retirement fund, scrape together his savings and pay the $17,780 tuition for a three-month course at Hack Reactor.

Flash Has Crashed

In the time leading up to his decision to attend the school, Webb had been forced to dip into his savings to provide for himself, his 3-year-old son and his 1-year-old daughter. He and his wife had also begun their separation, a process “that significantly impacted” Webb’s finances. Unlike other students who attend coding camps, Webb didn’t have a large network of support to rely on. His dad is a truck driver and his mom works at a community garden.

But going to Hack Reactor was vital. When teaching himself to code a decade ago, Webb focused on Flash, a language that was once ubiquitous across the internet but fell out of favor after being denounced by Steve Jobs in 2010 — an event that changed Webb’s life and continues to haunt him.

Paying for tuition would be one thing, but Webb knew he also needed to brace for the many months he’d be away from contract jobs, occupied studying and looking for work. He did a few last rounds of contract jobs to fortify his savings, and he cashed out his 401(k). He was betting everything he had.

1,000 Hours Of Coding

From March to June of this year, Webb would begin his day with a one-hour commute from Castro Valley, across San Francisco Bay and into downtown San Francisco, where Hack Reactor is based. He’d spend the day coding from dawn to dusk, with lectures in between. He’d stay late many nights, coding after his peers had left so he could finish up after-hours assignments before heading home on another hourlong train ride. “I would stay especially late and get my work done there so I could be present in case my kids were awake," Webb said.

This went on for 12 weeks, every Monday through Saturday. Webb put in more than 1,000 hours total refining his skills. But being the only black person in his class left him feeling alienated at times. “I don’t mean to imply that I felt alien because of anything that anyone else did,” said Webb, explaining that his classmates were great and that Hack Reactor spent a large deal of time saying it would not tolerate racism, sexism, ageism or any others “isms.” “It was a great environment to learn in.”

But still, it can be hard to feel included when you’re the only one like you.

As he’d code, he’d overhear his predominantly white and Asian male classmates talk about how their mom was helping them pay tuition, how they didn’t have to worry about housing because grandma was hosting, or how they didn’t have to find a job immediately because they were going on vacation first. “It’s just those kinds of things that I just couldn’t relate to because I am check-to-check right now, and I really need this to work,” Webb said. “Quickly.”

Additionally, Webb was under a lot of pressure dealing with his separation and adjustment to single parenthood, said Pamela Greenberg, a counselor at Hack Reactor. “He was trying to find a way to translate his skills, which were mostly self taught at that point, into a career that could provide for his family,” she said. “That manifested as a lot of anxiety.”

At times, these challenges would psyche Webb out. He’d get stuck on a problem then worry he’d never find the solution. Webb was running into a problem called imposter syndrome, Greenberg said. “It’s when somebody thinks that they’re not going to fool people and someone is going to see through them,” she said.

“Justin has tremendous skills,” Greenberg added, “but he didn’t always trust himself.”

Greenberg and Webb worked together, and over time, he learned to believe in his abilities once again. Then he shined, Greenberg said. Webb built a range of projects with his peers, including a fitness and workout tracker for the CrossFit community and a tool for his thesis called Constellation that helped programmers find and fix issues within their projects.

“He was somebody other students looked up to and somebody who had a life experience to share with people," Greenberg said.

Webb did so well that his peers elected him to serve as a hacker in residence, a three-month, part-time paid position where Webb would be responsible for mentoring the next batch of students. Honored, in need of the immediate revenue stream and needing more time to bolster his portfolio, Webb eagerly accepted.

Hacker in Residence

Webb’s residency took place at Telegraph Academy, a new Hack Reactor sister school in Berkeley designed to bring more individuals from underrepresented groups into tech.

It was a different experience. At Telegraph, there were about 15 students and nearly half were black while a handful were women.

“There were a lot more people who could relate to my financial struggles more clearly,” Webb said. While at Hack Reactor, he often had to explain to his peers why he couldn’t go out for drinks, at Telegraph Academy he never had to have those conversations because his peers were in similar situations. “There were fewer points I had to make or differences I had to notice.”

About four weeks into his residency, Webb caught wind of a freelance opportunity he thought could help him bring in cash and grow his portfolio. He took it on, but right away, he realized it was more complex than he thought it’d be. Between the demands of his residency and long commute, he didn’t have much time to work on the project.

“It was more than I could handle,” said Webb, who enlisted his fellow residents to help him with the project, which remains unfinished, though Webb said he intends to complete it after he lands a job.

Job Hunting Is Work

Webb kicked off his job hunt as soon as his residency ended in late September. Among one of the early jobs he applied to was a position at GitHub, a service used by hackers to share code.

GitHub liked the work he and his partners had done on their thesis, and in October, the company invited them to apply for jobs. “GitHub is the kind of company that you tell other engineers you work at GitHub, and even they are impressed,” an ecstatic Webb said. “That would be a dream to get in there.”

But as the hunt progressed, Webb was becoming stretched with his time and money.

Applying and interviewing for software engineering roles is a process that requires applicants to do a lot of what amounts to unpaid work. Companies require that applicants take on “coding challenges” before deciding whether to bring them in for an on-site interview. Those who get an invitation are again grilled on their skills and asked to “white board,” meaning solve coding challenges and show their approach to programing as potential employers look on.

“The job hunting process is work itself,” Webb said. Candidates have to pay for transportation. They have to focus entirely on these coding challenges and ignore other projects. They have to spend money on the food they eat when they head into San Francisco. “I feel like a lot of my brothers and sisters might run into a lot of the same challenges that I experienced,” the financially strained Webb said. “It’s not just an interview process for us.”

“They’ll talk to you because they have to, but if there’s anyone else, they’ll go with them instead."

‘You’re Not a Fit’

This became all too true for Webb one day in November. Walking back from his train after a long day of work at Hack Reactor, he opened the door to his apartment complex, and 4 feet from him, he saw folded white papers stuck to his front door. Inside was an eviction notice.

Webb was eight days late paying rent and management wanted its money. He thought of GitHub and all the other companies he was waiting to hear back from. He needed a company to pull through for him.

His mind also flashed back to 2001, when he was helping take care of his mother and sister. His struggles had gotten so great he was forced out of his apartment and into living in and out of hotels, on the brink of homelessness. “I’ve always been afraid that I would end up back there, even when I was earning good money,” Webb said. “It’s always in the back of your mind.”

Facing eviction as well as perpetual rejection, Webb found himself in a state of depression. He pooled together funds from his friends, promising to pay them back as soon as he could, so he could cover November rent — he hated having to do that.

He tried keeping a positive spirit, but even his candidacy at GitHub had hit a snag. Webb made it through numerous rounds of interviews and his thesis partner, a young Asian woman, had already been hired by the company. But what Webb previously believed was his final interview for the job turned out to be the fourth round in a six-step process. He was happy to still be in the running, but GitHub’s leisurely process was adding to his strains.

“I’ve almost given up on [GitHub] because I am pretty much broke otherwise,” Webb said. “I don’t know how I’ll pay December rent.”

Adding to the pressure, a friend, another black engineer, warned that she felt companies tend to drag their feet on black candidates. Webb was starting to believe it.

“They’ll talk to you because they have to, but if there’s anyone else, they’ll go with them instead, or at least that was the perspective that was shared with me,” Webb said. “I don’t exactly think that way, but it’s hard to maintain my positive mind-set when I apply for a job I feel I’m totally qualified for, maybe even qualified for the senior level, and I hear back ‘you’re not a fit for either.’ ”

Adding to his worries was seeing his Hack Reactor peers, his fellow residents and his Telegraph students all finding work. They were getting jobs at AOL, Vevo and popular startups like Lending Club and Getaround. He was getting rejections.

“I can’t say that the entire market is like this for all black folks or that I’ve run into anything overtly racial, but when it’s all said and done my experience mirrors a couple of other people who’ve been having difficulty,” he said.

Adding insult to injury, Christmas was coming up and so was his daughter’s birthday on New Year’s Eve. “The hardest part of all this is trying to keep up a facade so they don’t perceive me struggling and making sure they have everything they need,” he said. “I don’t want them to go to day care and hear about all these Christmas celebrations and not see any of that spirit here at my house. And I don’t even have any presents under the tree yet.”

Hack Reactor, which like most code academies takes a keen interest in job placements, noted that since Webb didn't start his search until September, he's still in what they called a "normal 3-month job search phase.”

Time, however, was running out.

A Full-Court Press

Webb avoided eviction again in December by promising to find a job before Christmas. He put his side project on hold, and most importantly, he opened up to Hack Reactor about his situation, asking for any help he could get.

Hack Reactor helped him retool his résumé and then went on what he called “a full-court press," putting his résumé in front of as many people is it could. As tech companies head into the fourth quarter, many try to resolve issues like lingering projects by year’s end and need extra hands to get it done.

“I’m dealing with a time crunch. They need someone with my skills,” Webb said. “Perhaps we can help solve each other's problems.”

Unfortunately for Webb, GitHub rejected him in mid-December, saying they didn’t see him as a fit inside the company, despite passing the most recent challenge. “If the way I passed the test wasn’t right enough, I could’ve learned the right way to get the answers right,” Webb said. “But hearing 'right' wasn’t right enough was frustrating.”

One of Webb’s major differences from “your garden variety engineer” is his age. Webb's being almost 40 and competing with 25-year-olds is certainly a factor, said Gerald Harris, an African-American consultant living in San Francisco who’s been doing strategy-related work with Silicon Valley over the last 20 years.

“He may be reporting to people who are 10 years younger than him,” Harris said. “If those people are uncomfortable with him being black as well as uncomfortable with him being an older person, he has a double mark against him that he has to deal with.”

But that’s no reason to give up, said Harris, who has not met Webb but understands the tech industry’s hiring practices. “If he is truly talented, there are enough startups, enough things going on out here that he could still luck into the right thing.”

Webb shared Harris’ optimism. “Something is going to happen, something good.”

A Silicon Valley Coding Christmas Miracle

Something did.

With 10 days to spare before Christmas, Webb was offered a job, and for the first time in a long time, he felt “alive inside.”

“I feel like myself again,” he said.

The offer came from WorkSpan, a software-as-a-service develop application startup in Redwood City, South 25 miles from San Francisco. It was one of the companies Hack Reactor connected Webb with earlier in the month. The whole process took about one week and just two interviews.

“It’s really hard not to accept the offer outright,” said Webb on Tuesday, at the time still in the running for two other jobs.

Two days later Webb took the offer. It includes a six-figure salary, or a “handsome compensation” as Webb puts it, and a few extra perks. It’s an offer that Webb said will help him keep his promises and take care of his children's Christmas gifts. More importantly, it ensures his children will not have to live out of a hotel room as he once did.

“Making sure that my kids never have to go through that, that they can have a good Christmas as far as they know, that means everything to me,” Webb said. "I'm very happy. Long nightmare is over."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.