Boko Haram And Nigeria's Economy: Why The Poorest Suffer Most

Nigeria has broken two records in 2014. First, it became the largest economy on the continent after rebasing its GDP. It also experienced the deadliest attack yet from militant Islamist group Boko Haram, whose members killed 300 people two months later.

These are twin problems for a country whose massive economic growth has, in many cases, furthered the divisions between its commercial, southern states now home to dozens of multinational companies and a growing middle class, and its poverty-stricken unstable northern region, where Boko Haram dominates.

“Nigeria’s north is definitely poorer than the south and the conflict is having a negative impact,” Amadou Sy, Africa economist at the Brookings Institute, told IBTimes, adding that the former depend a great deal on transfers from the latter, though many are seriously concerned about how this happens amid corruption issues.

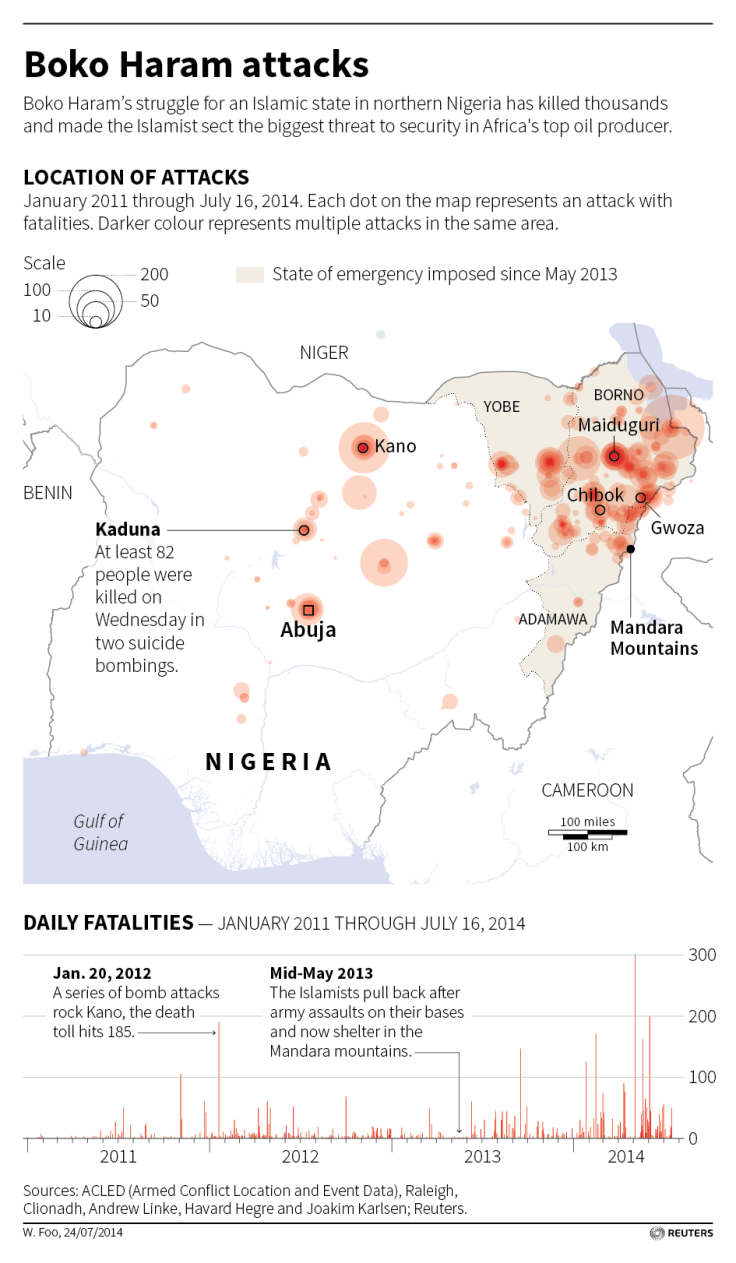

Made famous earlier this year after kidnapping more than 200 girls from the Chibok region in the northern state of Borno, Boko Haram has been operating in the sparsely populated north for more than five years. Despite killing hundreds and displacing thousands, Nigeria’s economy has continued its meteoric rise, with foreign investors scrambling to get a piece of Africa’s most promising market.

At the moment, the only economic impact the group has had is slowing down production in a region that is already struggling. Agriculture accounts for roughly a fifth of the nation’s GDP and employs more than 35 percent of youths aged 18 to 35, and is starting to show signs of strain.

It’s concentrated in the northern states, which are also those with the highest poverty rates and the majority of Boko Haram’s activity.

“In some parts of the north, the security situation has affected farmland production and that has led to some increase in food prices,” Central Bank of Nigeria Deputy Governor Kingsley Moghalu said to CNBC earlier this week.

Food prices rose 9.8 percent in June, and inflation hit 8.2 percent, the highest its been in 10 months, according to Nigeria’s national statistics bureau.

“The effects of conflict on the agricultural sector are largely due to the risk of being attacked by insurgents,” according to a Brookings report published this week.

The researchers wrote that, the industry is under a few different strains. First, is the simple problem of human mobility.

“People across all value chains feared movement outside protected areas because of attacks by insurgents,” they wrote, explaining that farm workers feared attacks while grazing animals, processors lost workers when families left the conflict zone, and traders began limiting their movements. Meanwhile, the agricultural sector became a target for militants in need of supplies. Their data shows that cash, food and equipment were more likely to get stolen. Lastly, the danger has made other things like transportation more risky and therefore more expensive, again putting pressure on the economic output.

“The impact of [Boko Haram] on the Nigerian economy is localized for now, but the instability has had an effect on the agricultural products from the north and has severely reduced cross-border trade with Cameroon, Chad and Niger,” the report says.

However, the impact is still most felt in these northern states, which have always been far from Nigeria’s positive development story. Indeed, though the number of Nigerians living in poverty has increased 55 percent in the past decade, the number of Nigerian millionaires topped 15,700 last year, up 44 percent since 2007.

The country has been one of the largest recipients of foreign direct investment in the region, with inward flows jumping 28 percent to hit $21 billion last year.

On a macro level, Nigeria shows no signs of slowing down, even as the violence increases.

The stock markets remained relatively stable, and even the currency showed no real volatility, besides a drop in February when the former central bank governor Lamido Sanusi was suspended.

“The impact on the economy has actually remained muted given that the violence did not spread to Lagos or the oil-rich Niger Delta,” Samir Gadio, emerging markets strategist at Standard Bank, said to International Business Times in May.

“Portfolio investors appear to largely discount the security issues associated with Boko Haram while there has been very little FDI in this part of Nigeria anyway,” he added.

Even as attacks ramped up earlier this year, foreign companies showed no signs of slowing down in the central city of Abuja, where the World Economic Forum was held just weeks after the schoolgirls were kidnapped, or the commercial capital of Lagos, home to startup incubators, upscale cafes and luxury car dealerships.

“We’re not feeling the impact,” a 25-year old employee at a Lagos luxury shopping mall told The Globe and Mail. “We believe we are safe here.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.