Boycott China And Avoid A Trade War

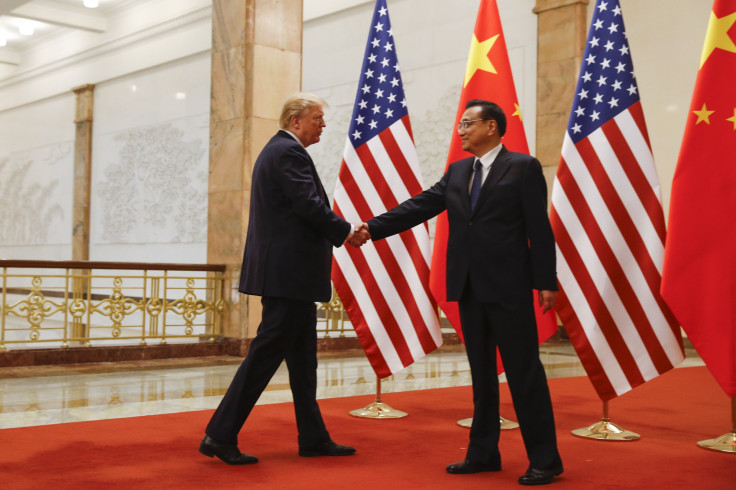

The U.S. and China are locked in negotiations both sides say they hope will avert a painful trade war.

The Trump administration has threatened to impose a series of tariffs unless China agrees to limit what he calls “its illicit trade practices.” The Chinese government, for its part, appears unwilling to accede to his demands and has offered some retaliatory trade sanctions of its own.

The ostensible reason President Donald Trump is willing to risk a trade war is because he argues – justifiably – that U.S. companies have been taken advantage of by their Chinese counterparts for decades, required to hand over lucrative intellectual property in exchange for access to China’s growing middle class.

Tariffs, however, aren’t the answer to that problem, as my research in international economics and the design of international environmental agreements shows. Rather, if Trump really wants to achieve his stated aims, he should put American businesses on the front lines of his strategy and call for a boycott of China.

Doing Business In China

If that sounds preposterous, consider the origins of this escalating conflict.

Its seeds can be traced back to the opening up of the Chinese economy as a result of reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping in 1978 and the zeal of American – and more generally Western – companies in taking full advantage of new business opportunities in this gigantic market.

However, in many instances in the past four decades, the presence of mandatory technology transfer policies and foreign ownership restrictions have meant that market access has been granted only to Western firms willing to play ball. In addition, there is now considerable evidence that Chinese businesses, often with the participation of government officials, have been conducting cyberattacks on American companies to steal their intellectual property.

The Trump administration estimated that this theft of American intellectual property costs US$225 billion to $600 billion annually.

And since companies are already on the front lines of this fight, with the most to lose, it makes sense that they’re the ones to lead the counter attack.

A Boycott By Firms

So how would a boycott work? Importantly, the U.S. couldn’t do it alone.

American companies, like everyone else, want to make money in the one billion person market that is China and hence it would not make sense for them to unilaterally withdraw. By doing so, they would be giving up valuable market share to their rivals. For example, if a top U.S. luxury car seller such as Cadillac were to unilaterally boycott the Chinese market, then it would be giving up valuable market share to other rivals.

The key point is that many of those rivals are in Europe and have also been used and abused by Chinese companies and hence have a similar interest in finding a way to prevent them from stealing any more of their intellectual property.

If all Western luxury car makers jointly boycotted China, then this would be equivalent to acting as if a Chinese market didn’t exist. Clearly, profits would take a hit in the short run, but the long-term objective of ensuring that Western companies do business on a level playing field would be met.

Cars And Chips

Also, a boycott wouldn’t have to involve more than a few industries to be effective. Specifically, the focus would need to be on industries that China, through its Made in China 2025 scheme, would like to dominate. Two strong examples are cars and computer chips.

China has been trying to develop a domestic automobile industry since the early 1980s, an effort that has largely failed. But now, under the Made in China initiative, it is seeking to become a leader in electric vehicles.

However, it needs Western automakers to continue to operate in Chinaand conduct research on battery technology and on electric vehicles in order to achieve this goal.

Thus if Western car companies and particularly those actively conducting research in battery technology jointly agreed to stop competing in China, that would send a strong message to Beijing. Either China could try to go it alone with no Western collaboration or it’ll have to realize that systematically strong-arming companies will not help it attain its goals.

A second example of an industry in which a Western boycott would be effective is microprocessor chips. This is because China is still significantly dependent on imports despite operating a few notable supercomputers that use solely home-made chips. Almost 90 percent of chips used in China are either imported or produced domestically by foreign companies, so a boycott would force the government to sit up and take notice.

For a boycott of this sort to work, it is important that American officials not attempt to go it alone, making it seem like a purely China versus U.S. spat. Successful boycotts follow a “strength in numbers” logic.

And this is where the Trump administration enters the fray. It could use its diplomatic muscle to enlist the governments of like-minded allies – particularly the European Union – to get their companies in key industries to join the American-led boycott. This could be part of a wider effort to credibly and collaboratively communicate to China that it needs to play fairly. As New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman recently noted, the “last thing Beijing wants is a U.S.-E.U. united front demanding it play fair.”

Not only would this selective boycott make it harder for the Chinese government to achieve its Made in China 2025 dreams, it would also anger consumers, who are increasingly hungry for Western goods – something the leadership is well aware of.

And in contrast to tariffs, such a campaign would likely have no adverse impact on American consumers.

One important caveat: This course of action, like imposing tariffs, would probably do little to reduce the threat of intellectual property theft by Chinese hackers.

Would A Boycott Work?

When we think of a boycott, we usually imagine consumers avoiding a particular product. Such boycotts have had varying levels of success.

A corporate boycott of a nation is much less common. To the best of my knowledge, a corporate boycott of a nation along the lines suggested here has not been attempted before. Historically, boycotts against a nation have typically been designed to persuade consumers to not purchase products from a nation, such as the anti-apartheid movement or the more controversial boycott of Israel.

What I am proposing is a country boycott by companies located in multiple nations and hence it is not possible to directly gauge the likelihood of success based on past actions

That being said, vigorous diplomacy by like-minded nations sharing a common objective has yielded positive outcomes in as diverse and difficult cases as the 1987 Montreal protocol to reduce ozone-depleting substances and the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. Similarly, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries cartel has demonstrated how businesses across nations can take joint action to achieve a common objective, with mixed success.

Might China retaliate? Perhaps, but the costs would be high if the U.S. were to successfully organize a boycott involving companies in several dozen countries. More likely, it would find accommodation a much more palatable option in the face of a united front.

The recent tariffs aside, Western businesses and nations need to stop treating China with kid gloves, which I believe they have been doing for years. A boycott would be a good start – and wouldn’t risk a trade war.

Amitrajeet A. Batabyal is an Arthur J. Gosnell Professor of Economics at Rochester Institute of Technology

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the article here.