Brazil's Lula Seeks Latest Upset: Win Back The Center

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who started out a shoeshine boy and became the most popular president in Brazilian history, has racked up a lifetime of improbable victories.

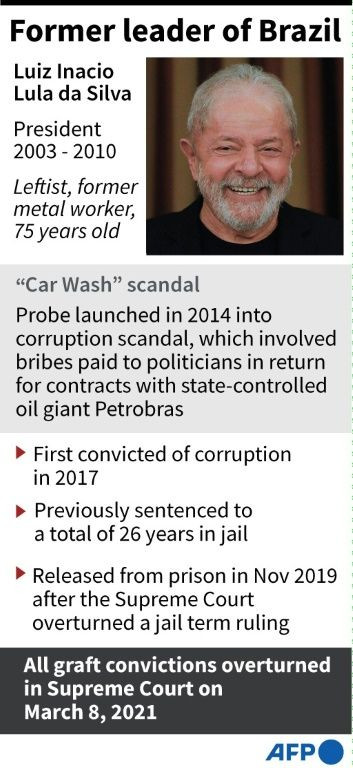

Now, as he eyes a run against far-right President Jair Bolsonaro next year, the 75-year-old leftist leader is seeking another: win back the political center that abandoned him in disgust when he was jailed for corruption in 2018.

It is still early to predict the October 2022 election, but polls show it shaping up as a Bolsonaro-Lula showdown, likely headed for a runoff.

That means the next leader of Latin America's largest economy may well be decided by a battle for the grudging votes of the more than one-third of Brazilians who intensely dislike both.

Pulling off a presidential comeback would be nothing short of astounding for Lula, whose towering legacy collapsed when he was convicted of taking bribes -- part of a massive investigation into a multi-billion-dollar corruption scheme involving state-run oil company Petrobras.

But it would not be the first surprise from the former steelworker and union leader, who rose from poverty to become a two-term president from 2003 to 2010, leading Brazil through a transformative boom.

To pull it off, the charismatic but tarnished veteran would have to win back at least some of the middle-class voters and business elites who punished his Workers' Party (PT) at the polls in 2018.

In a deeply polarized Brazil, Lula is striving to sell himself as a moderate to the alienated middle.

"Lula is a versatile animal who has gone back and forth over the past four decades, from far-left in the 1980s to a centrist partnering up with conservatives" in the 2000s, said political scientist Oliver Stuenkel of the Getulio Vargas Foundation.

"Now he's back in governing mode," he told AFP.

"He's clearly positioning himself more as a centrist."

Lula, who spent 18 months behind bars, regained his eligibility to run for office in March, when the Supreme Court annulled his convictions on procedural grounds.

He wasted no time holding a campaign-style press conference, where he attacked Bolsonaro and laughed off the 66-year-old incumbent's warnings that he is a radical.

"Don't be scared of me. They say I'm a radical because I want to get to the root of this country's problems," he said.

Lula has not officially declared himself a candidate.

But he flew to Brasilia earlier this month for meetings with a host of political bigwigs, including from the powerful center-right.

He then had lunch in Sao Paulo with longtime political enemy Fernando Henrique Cardoso, his centrist predecessor.

Lula tweeted a picture of them exchanging a fist-bump.

"He's doing what you do in politics: starting to sew potential alliances, talking with parties, seeing what each one wants," PT Senator Jaques Wagner, a longtime friend, told newspaper Valor Economico.

So far, it appears to be going fairly well for Lula.

"We've already seen immediate results from those meetings as far as political elites go. Leaders of various parties have been praising Lula, or at least being cordial," said political scientist Mayra Goulart of Rio de Janeiro Federal University.

As he eyes a sixth run for president, Lula, who made three unsuccessful bids from 1989 to 1998, looks to be returning to his playbook from his first winning campaign, in 2002.

Seeking to convince Brazilians he was not a radical rabble-rouser, he promised them then: "Little old Lula wants peace and love."

Indeed, he went on to govern as a moderate, mixing market-friendly policies with anti-poverty programs.

When he handed power to hand-picked successor Dilma Rousseff, he was basking in 80 percent popularity.

Many of those Lula is courting are desperate for a centrist alternative.

But the electoral math looks stacked against them.

As in 2018, around 30 percent of voters are expected to abstain or cast blank or spoiled ballots.

Of the remainder, polls show Bolsonaro and Lula have about 25 percent each.

"Any centrist candidate will have a very hard time making it to a run-off," said consultancy Eurasia Group.

And the field is crowded with would-be candidates, including governors, entrepreneurs, a TV personality and the judge who jailed Lula, Sergio Moro.

But in a sprawling country of 212 million people, all have struggled to achieve national name recognition.

Lula has meanwhile launched his comeback name-checking his old acquaintance Joe Biden and giving interviews to The Guardian and CNN's Christiane Amanpour.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.