Brexit And The EU’s Branding Problem

The bigger the prize, the greater the need for human connection.

Despite the European Union’s tremendous economic, environmental and social benefits, its leaders have failed to build a belief and sense of belonging for many of its citizens. This is particularly clear in Britain through Brexit, and in the rise of the far right across Europe. European leaders’ reluctance to engage the value of creating stronger emotional bonds has ensured a vacuum that people look to fill through their national identities. While national identity will always be significant, the EU’s lack of brand building will result in almost unquantifiable loss and instability.

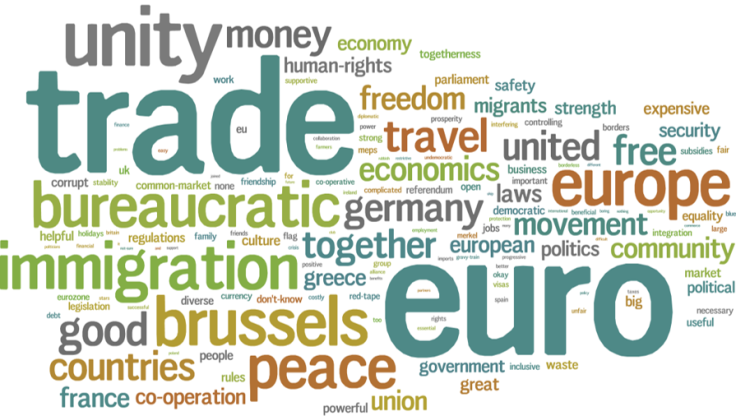

One in four European voters are seeking to elect populist candidates to support their desire to protect nationalist issues. And, the United Kingdom is leaving the EU. Research we conducted in the U.K. during the lead-up to the referendum showed that the biggest difference between intended “Leavers” and “Remainers” was not what they cared about, but what the EU represented for them. For Remainers, the words that first came to mind were trade, euro, unity, peace; and, not dominantly, bureaucratic and immigration. For Leavers, the key words were expensive, waste, immigration, bureaucratic and corrupt. Among other differences, for Remainers, the EU meant the multinational community they were part of; for Leavers, it meant the institution that administers it.

Britain’s citizens have little idea what they have been part of or are about to lose because the EU is missing a brand to provide a clear sense of purpose. People feel like they are part of something they don’t understand or feel anything toward. For too many, the EU is just a background noise of institutional intractability, with none of the glamour or reflected glory that it could have, given the underlying strengths that the Remainers in our survey recognize.

With tremendous finance clout, collective resources, highly educated populations, cultural diversity, military muscle, and historical richness, the EU is an extraordinary powerhouse of collective might and opportunity. So why don’t most people inside want to be a part of this? The U.S. and China court it, and Russia fears it. Yet, not many Brits nor a good number of Europeans love or care about the EU.

The EU has a flag, it has the euro, it has Brussels as a headquarters; it also has a powerful, although seldom heard, anthem – Beethoven’s Ninth – but that’s about it, as far as most people can see. For the Brit in the street, there are no symbols to capture affinity with the European idea. There is no BBC, no NHS, no EU teams to support, no public holidays, no shared goals, in short, nothing to feel allegiance to. Even where there are symbols, opportunities are missed: the euro notes themselves are decorated with generic, anonymous historic building styles, not any of the actual great buildings in the EU, for fear of favouring one country over another.

The EU has created no shared rituals, buildings, uniforms or other symbols representing it, and most importantly has no news stories beyond regulation, so little wonder that it struggles to attract attention and affection from its citizens. Like all brands that don’t control their story, it allows others to dictate it for them. For the Brits, this story is about unneeded, mundane, bureaucratic meddling.

The leadership in Brussels has failed to build the EU into a recognizable and understood brand that captures the Union’s combined strength, potential and values: an idea that sets direction and drives a sense of belonging. The U.S. evokes ideas of freedom, the land of opportunity, the home of the “American dream”, an idea that drives a work ethic, entrepreneurialism and loyalty. It also has states like California, Texas and New York that are as different as Spain, France or Poland.

Could the EU ever overcome local allegiances? It requires a portfolio of emotion-building initiatives and myth creation. It requires the leadership to understand that the heart is won by emotion, not pragmatics, and it requires articulating and celebrating the purpose of Europe in the world.

It needs a will and vision, to see beyond single-minded nationalism to provide a force that can guide a divided world in need of compassionate leadership on a big scale, to overcome climate change, a growing list of humanitarian issues, as well as economic stability and sustainable livelihoods. This is not a job for any one country, it’s a task for nations to get behind and help build the symbols and symbolism of the European character and values, to win over hearts, not just officials.

Lee Coomber is creative director for Europe and the Middle East at Lippincott, a brand and innovation consultancy founded in 1943.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.