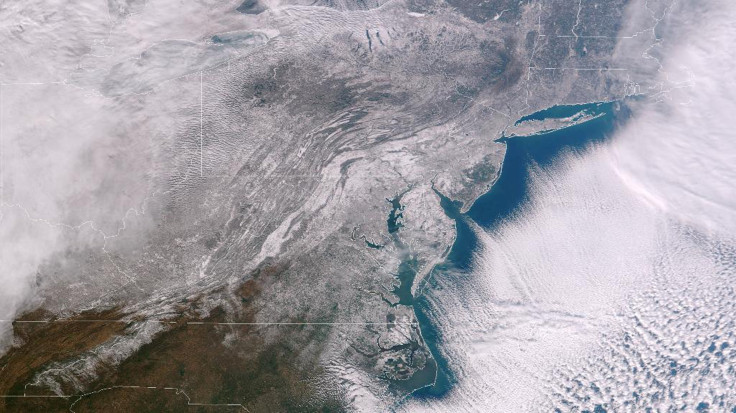

Brutal Winter Caused By Changing Jet Stream, Scientists Say Warming Arctic Temperatures Are To Blame

Winter storms, especially in North America and Europe, seem nearly endless these days. After one marches through and dumps its freight, another is just a few paces behind. What’s worse, the bitter winter weather we’re experiencing could be the start of a long-term trend.

A recent study of global weather patterns is helping scientists understand how a changing North Atlantic jet stream could mean that colder, longer winters are here to stay.

According to new research presented at American Association for the Advancement of Science in Chicago, the jet stream over northern Europe and North America is taking a longer, more meandering path. As Wired notes, the jet stream, which flows from west to east around the northern hemisphere, separates warm air masses moving towards the poles from the tropics and cold air masses heading south from the poles.

Its strength is directly proportional to the difference in temperature between the tropics and the poles. When the difference is less pronounced, the jet stream tends to meander. And with temperatures in the Arctic rising two to three times faster than the rest of the globe, the difference in the temperatures of the air masses is weakening. That means longer winters across North America and Europe.

"The temperature difference between the Arctic and lower latitudes is one of the main sources of fuel for the jet stream; it's what drives the winds,” Jennifer Francis, professor at Rutgers University's Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences, said in a statement, according to NPR. “And because the Arctic is warming so fast, that temperature difference is getting smaller, and so the fuel for the jet stream is getting weaker. When it gets into this pattern, those big waves tend to stay in the same place for some time. The pattern we've seen in December and January has been one of these very wavy patterns.”

According to NASA, temperatures in the Arctic increased on average by about 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.2 degrees Celsius, every decade since 1981. “When compared to longer-term, ground-based surface temperature data, the rate of warming in the Arctic from 1981 to 2001 is eight times larger than the rate of Arctic warming over the last 100 years,” NASA scientists noted.

A warming Arctic means winter weather patterns will become stuck over areas of North America and Europe for weeks on end. It also drives cold weather further south and warm weather further north. But scientists say the situation is more nuanced than predicted by a simple correlation.

"It doesn't mean that every year the U.K. is going to be in a stormy pattern," Francis said. "Next year you could have very dry conditions, and for that to be persistent. You can't say that flooding is going to happen more often. Next year may be dry, but whatever you get is going to last longer."

Alongside Francis at the American Association for the Advancement of Science panel was Mark Serreeze, the director of the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center. According to Serreeze, the area of study concerned with a changing polar north and its influence on mid-latitude weather is a burgeoning field of research.

"Fundamentally, the strong warming that might drive this is tied in with the loss of sea-ice cover that we're seeing, because the sea-ice cover acts as this lid that separates the ocean from a colder atmosphere," Serreze said. "If we remove that lid, we pump all this heat up into the atmosphere. That is a good part of the signal of warming that we're now seeing, and that could be driving some of these changes."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.