The Buffett Rule: Where It Stands, How It Works, And Why It May Not Be Enough

Analysis

The Buffett Rule is a plan that would raise taxes on America's most wealthy, requiring those making $1 million or more per year to pay a minimum federal tax rate of 30 percent on all income.

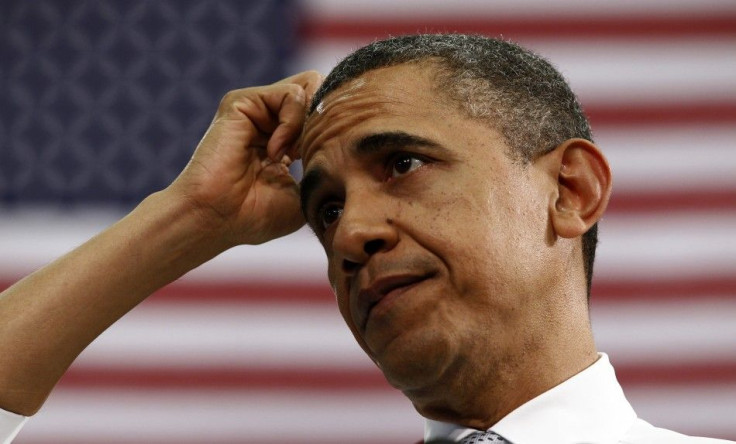

On Tuesday, Obama pitched the idea to a group of university students in Florida. You may have heard this, he said, but Warren Buffett is paying a lower tax rate than his secretary. That's wrong. It isn't fair. And it's time for us to choose which direction we want to go in as a country.

Buffett's name is on the proposal because he pushed for the idea last year. The billionaire investor published an opinion piece in the New York Times arguing that he and his peers ought to be paying a larger share of their income to the federal government.

In response, Obama pushed legislation that would make Buffett's wish a reality. Back then, the proposal went nowhere. But now that presidential elections are once again upon us, the Buffett Rule is back on the table.

The idea is sparking heated debates -- taxation is a touchy subject, as well as a complicated one. The big to-do merits a closer look at how U.S. taxes are structured, what sorts of changes Obama is pushing, and why exactly he's pushing them now.

A Breakdown of Progressive Taxes

Currently, there are six federal income tax brackets in the United States, with rates ranging from 10 percent to 35 percent. The system is nominally progressive, which means that those earning less income pay a smaller percentage of each paycheck to the federal government, while those earning more pay a larger fraction.

For instance, a single citizen with no dependents and a $20,000 salary will pay just 15 percent of their money back to the federal government, but a single filer who earns $300,000 will pay 33 percent.

Under this tax code, you'd think Warren Buffett would already be paying a higher percentage of income than his secretary does. But there's a catch: income taxes don't account for all the ways that people actually earn money.

Many of the very rich don't get all of their earnings in the form of a taxable paycheck -- instead, they make what are called capital gains: dividends from trading assets like stocks, bonds, and property. Those earnings are taxed at just 15 percent.

That means that if you make a great living by trading stocks and bonds all day, you effectively pay the same federal tax rate as someone making $20,000 a year. It's a giant loophole that negates the apparent progressiveness of our federal income tax system.

Furthermore, even basic paycheck-based tax codes aren't always progressive when you get down to lower levels of government. Many state and municipal tax codes are actually regressive, meaning low earners pay a higher percentage of their income than do high earners. The top three worst offenders for income tax regressiveness are Washington, Florida and South Dakota, according to a report by the Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy.

All in all, this adds up to a system that skews in favor of the wealthy. The Buffett Rule aims to change that.

Dialing Back to Close the Gap

Opponents to increased tax progressiveness argue that it would hurt the economy by stunting job growth and discouraging success. But the United States has a long record of taxing the rich at much higher percentages than we do today, and those policies didn't appear to damage growth. In 1960, the super-rich paid a whopping 70 percent of their payroll income to federal taxes, according to a 2007 report from the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Today, they pay only 35 percent of payroll income to the federal government. And when you look at total income including capital gains, the tax percentage shrinks even further; the White House report pegs the figure at about 26 percent. Federal tax code changes over the past few decades have overwhelmingly favored the richest Americans, so that millionaires and billionaires now enjoy some of the lowest federal tax rates in American history. This is thanks in large part to policies implemented under Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. Even Obama has gotten into the act by calling for cuts on corporate tax rates.

The middle class, on the other hand, has actually seen an increase in tax rates since 1960.

This overall pattern has contributed to a growing net earnings disparity between rich and poor Americans. By 2007, just before the recession, the income gap had grown to levels unprecedented since 1929.

In its historical context, the Buffett Rule looks more like a slight dial-back than a major reform. Since it would affect only those earning $1 million a year or more, the measure would do relatively little to turn back the high tide of economic inequality.

Hope and Chump Change

The Buffett Rule has been codified somewhat vaguely in the Paying a Fair Share Act of 2012, which is scheduled for a Senate vote on April 16. Extra income from closing the capital gains loophole could benefit the national economy by raising revenues of about $46.7 billion over the next ten years, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.

This is no small sum, but in fact it barely makes a dent in the U.S. national deficit and would have a small impact on the federal budget.

More importantly, the Buffett Rule isn't likely to be enacted, and Obama knows it. Chances are slim to none that the Republican majority U.S. House of Representatives will let the bill through.

But backing the measure gives the president a powerful talking point in the lead-up to the November election. Faced with presumptive Republican candidate Mitt Romney, who has been blasted by critics for seeming out of touch with average Americans, Obama knows that touting the Buffett Rule gives him the populist edge.

[Romney] thinks millionaires and billionaires should keep paying lower tax rates than middle-class families. In fact, Romney himself isn't paying his fair share, said a statement from the Obama campaign. Tax forms released by the Romney campaign show that he made $21 million last year and paid only about 14 percent of that in taxes.

Rhetoric like this will serve Obama well in November, and that's the real purpose of the 2012 Buffett Rule legislation. Even if, by some fluke, the bill passed in Congress, the Paying a Fair Share Act would do little to address existing problems with federal tax codes.

A bigger opportunity for change will come up at the end of this year, when Bush-era tax cuts for those making $250,000 or more are set to expire. Obama has called on lawmakers allow the tax codes to revert to their pre-2001 status, and that could benefit the U.S. economy to the tune of $800 billion over the next decade.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.