Bullets Beyond Recall: Defective Guns Outside US Government's Reach

A string of faulty product allegations against one of the world’s largest gun manufacturers is reigniting the tension between consumer safety and America’s affection for unregulated firearms.

ALBUQUERQUE — The night Judy Price got shot with her own gun she’d been walking the dog on a ridge above the Rio Grande. It was two days before Thanksgiving in 2009 and chilly enough to wear her new mint-green sweat suit as she and Cody, a fluffy Samoyed, set off into her Albuquerque, New Mexico, neighborhood of flat-roofed homes and rock landscaping. Underneath her sweatshirt, Price carried her semiautomatic pistol against her belly.

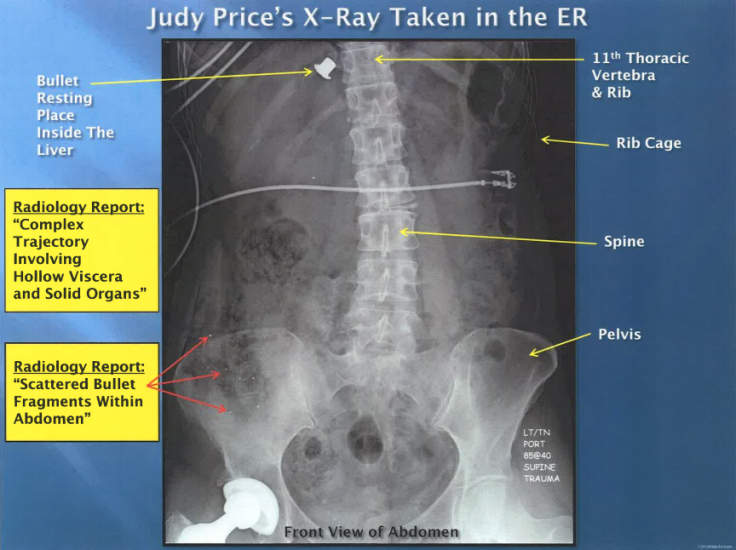

When she arrived home, Price began to undress in her small walk-in closet. Her husband, Paul, a retired explosives safety engineer, was sitting in the office across the hall. He heard the bang of a gun, and she saw a flame flicker at the muzzle. The gun lay on the floor, where it fell when Price took off her sweatshirt and got caught on her Velcro holster, tearing it loose. Later, she marveled at the groove the hot bullet left on her sweatpants as it traveled up into her stomach, tore through the internal organs along the right side of her body and lodged in her liver, where it rests to this day.

Unlike virtually any other consumer product sold in the United States — from toasters to cars to medical devices — the federal government has no authority to force the recall of potentially defective firearms.

Modern-day guns like Price’s Taurus PT 140 are not supposed to go off when they fall to the ground, but Price says her gun was faulty. Her lawyer, who won a 2009 jury trial involving an unintentional firing from another Taurus-brand pistol, has a broader contention: The handgun Price purchased for protection, which she carried with her on church security patrols, is one of several Taurus models with inherent design flaws.

Those claims were the basis of a lawsuit Price filed against one of the world’s largest gun manufacturers, Brazil-based Forjas Taurus and its U.S. subsidiary, Taurus International Manufacturing Inc. Price endured 12 surgeries over the three years following her injury, and she can still feel the twinge of medical mesh holding her organs in place if she bends in a certain way. She settled her suit out of court. Her only face-to-face meeting with two company representatives came in August 2011. It ended on a hollow note.

“You have a serious problem,” Price remembers telling one of them. “You need to do a recall and deal with this issue, because the next person could die.”

In reply, Price, 59, says, one of the company’s representatives “looked at me and said, 'Mrs. Price, Taurus has no intention of doing a recall.'”

As the United States grapples with a rash of mass shootings, some are calling for tighter laws limiting who can purchase firearms — a politically controversial subject that has yielded more rhetoric than legislation. But another, lesser-known dynamic effectively shelters gun manufacturers from government oversight: Under legislation dating back to the 1970s, Congress has consistently adopted positions championed by the gun lobby and the National Rifle Association, writing special provisions that have effectively exempted firearms from regulation by consumer watchdog agencies.

The result is an only-in-America reality: Paintball guns are strictly regulated by the government, but the genuine article is generally bought and sold with no agency tasked with ensuring the product functions safely.

More than four years after her meeting with Taurus, Price is finally seeing her warning heeded, if too late for other alleged victims. She was not the first person to claim she’d been shot by a Taurus pistol that fired unintentionally, nor was she the last. Attorneys for alleged victims say that since 2005 at least 13 people have been injured in similar incidents involving various models of Taurus handguns. One person — an 11-year-old boy — was killed.

Taurus International Manufacturing denies allegations that its guns have defects. But under the terms of a pending class action settlement in a case brought by Iowa Police Officer Chris Carter, the company agreed to effectively recall nearly 1 million Taurus pistols — including the PT 140. Another gun on the list, the PT 111, is one that the company’s former CEO admitted during his testimony at a jury trial six years ago could fire when dropped.

A spokesman for Taurus declined International Business Times’ requests to interview company executives and did not respond to written questions for this story. “We are unable to comment at this point in the Carter settlement process, which has received preliminary court approval, or on other pending litigation at this time,” said Tim Brandt, director of marketing for Taurus Holdings Inc.

Taurus’ concession in the case is a legal landmark for a gun company operating in the U.S. It underscores a gaping regulatory hole for the 300 million guns Americans own: Unlike virtually any other consumer product sold in the United States — from toasters to cars to medical devices — the federal government has no authority to force the recall of potentially defective firearms.

If a maker of vitamin pills learns that a consumer landed in the hospital in connection with one of its products, the company is required by law to report the incident to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of hearing about it. If a manufacturer of children’s backpacks — or any of the 15,000 products overseen by the Consumer Product Safety Commission — learns of a defect that could pose a substantial risk of injury, the company has a 24-hour deadline to submit a report. Gun companies carry no such obligations.

Cementing these exceptions to safety oversight constituted a significant political victory for the National Rifle Association in the 1970s and helped pave the way for high-profile gun rights battles to come. Gun owners themselves, however, are left with little recourse to hold companies accountable for faulty products outside the civil court system. Whether gun manufacturers choose to recall a firearm is entirely at their discretion. If they do, there is no mandatory protocol to follow to alert owners, and no official repository of recall notices.

Often gun manufacturers “fail to act in a timely manner or to accurately describe the safety hazard,” argues the Violence Policy Center, which advocates for stronger gun regulations. This fall, the organization launched a project that culls safety alerts and recall notices from major gun companies. In mid-December it listed more than 40 such notices from 13 gun manufacturers. They include a Winchester Repeating Arms shotgun that could fire when its action is being closed; a type of Ruger pistol, manufactured between 1987 and 1990, that could fire when the safety lever is engaged; and a line of Smith & Wesson pistols that could fire if dropped because of reported problems with the trigger bar pin.

Experts can't pinpoint the exact number of deaths and injuries from defective firearms, because there is no national data that tracks it. But there were 215,422 non-fatal injuries from unintentional gunshots between 2001 and 2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same period, 8,383 people died from unintentional shootings.

The National Shooting Sports Foundation, the industry’s main trade group, declined to comment on product safety issues and gun manufacturers’ recall procedures.

The NRA declined to comment for this story and did not respond to questions about its position on gun product safety issues.

The absence of safety regulations raises the stakes for what lawsuits accomplish. Wins can be difficult to achieve. Federal law shields gun manufacturers from many types of liability for the use of their products. Gun manufacturers often blame victims for not handling their guns safely, attorneys say. Confidentiality agreements, common in liability settlements, shroud details in secrecy from others who have been injured or may get hurt.

The preliminary settlement in Carter's Taurus case — awaiting a judge’s final signoff in January — is significant due to its scope and because it is so rare. It’s one of just two proposed class action settlements in which a gun manufacturer has agreed to effectively recall its firearms. Under a pending settlement between gun owners and Remington Arms, the company said it would fix more than 7 million guns. The preliminary agreement in that case follows dozens of personal-injury lawsuits gun owners have filed over the past quarter century.

Only after Carter filed a class action complaint, and plaintiff's attorneys commissioned approximately 500 hours' worth of testing of Taurus pistols, did Miami, Florida-based Taurus International Manufacturing agree to a recall framework for nine models of its semiautomatic pistols. Carter, a deputy sheriff with the Scott County Sheriff's Office, alleges his PT 140 fired when it fell to the ground during a drug sting. No one was injured, but the gun shot out a car window, according to the complaint, which was filed in 2013 in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida.

Carter’s lawsuit contends there are two problems with certain Taurus pistols: a “drop fire” defect that allows the gun to unintentionally fire when dropped to the ground and a “false safety” defect in which the gun could fire even if the manual safety is engaged.

As part of the proposed agreement, attorneys say gun owners would be able to return their pistols to Taurus and receive either a cash reimbursement or a new pistol that included an improved trigger safety.

One of the biggest challenges for attorneys on the case is convincing gun owners that the lawsuit is not “anti-gun” but rather about alerting them to a potential safety hazard. “We say, Look, these cases have nothing to do with an individual’s right to keep and bear arms,” says attorney Todd Wheeles, himself a gun owner and a former agent with the Alabama Bureau of Investigation. “This is a product defect case, period. We’d bring this case if it were a blender or any other widget that was injuring or killing people. This just happens to be a firearm.”

According to multiple personal-injury complaints filed in court, the Taurus recall list also includes models that unintentionally discharged and wounded an Alabama man in his pancreas and left lung, a Washington state man in the groin and a Kentucky police officer in his right calf, fracturing his tibia.

IBT found that the recall list includes two models recommended to police officers as having earned a safety stamp of approval from the National Institute of Justice, a research body under the Department of Justice. According to Carter’s complaint, in 2013 the São Paulo State Military Police in Brazil, after discovering the risk of unintentional discharges, initiated a recall of 98,000 24/7 pistols — another model that’s included in the pending settlement agreement.

Slippery Slope

The gunshot that autumn night in 2009 turned Price into an unlikely crusader. The Prices, now both retired from civilian positions with the Air Force, own about 20 guns, and they hold them dear. Paul proudly displays his NRA membership card on his desk. Judy continues to carry a handgun — just not a Taurus.

In the wake of her injury Price began to assemble the pieces of a one-woman warning system. She’s gone to gun shows to hand out flyers depicting her bulging abdomen and a large hole carved into her stomach from surgery. She launched a website where she featured updates on her surgeries. She posted online a video re-enactment of the incident, complete with graphic images of her recovery process.

“I felt strongly that the accident should not have happened,” Price says. “I just didn’t want those things to happen to another family.”

For one Alabama family, attorneys say, the consequences were deadly. In February, Donald Dewayne Simms, his wife, Lisa Louise Simms, and their 11-year-old son, Donald Dewayne Simms Jr. — who went by D.J. — were gathered at their home in Cherokee County, a picturesque corner of the state located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. As Lisa and D.J. sat on the couch watching TV, her arm draped around her son’s neck, Donald Sr. was attempting to seat the magazine into a Taurus PT 609, according to a complaint filed in Miami-Dade county court.

Simms wasn’t touching the trigger, the suit says, but when he bumped the bottom of the gun, it discharged, sending a bullet through his left hand, his son’s neck and into his wife’s arm. D.J. died that night, Feb. 15. Friends remember him as a boy with a big smile and a penchant for giving out “free hugs.” Weeks after D.J.’s burial, according to the complaint, Simms says he learned that the class action lawsuit over Taurus guns had been pending for more than 18 months, and that the company had refused to remove pistols like the one he bought from the market.

If the company had issued a recall sooner, Wheeles says, “maybe D.J. Simms would be alive today."

In July, a federal judge approved the preliminary settlement between Carter and Taurus, allowing the mechanics of the effective recall to start grinding into gear. This major milestone, achieved nearly two years into the lawsuit, contrasts with the more routine machinery of the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the agency that Congress prohibited, first in 1972, from overseeing firearms. The CPSC monitors emergency room data to identify injury patterns, investigates consumer complaints and enforces companies’ reporting requirements about dangerous defects. It can sue businesses for violating those rules and to force a recall.

“We say, 'Look, these cases have nothing to do with an individual’s right to keep and bear arms.' This is a product defect case, period. We’d bring this case if it were a blender or any other widget that was injuring or killing people. This just happens to be a firearm.”

Most companies, however, choose to recall defective products voluntarily, albeit under the CPSC’s watchful eye. The same month Taurus entered the pending settlement, for instance, the CPSC announced 33 recalls by businesses, relaying information about the problem, the solution (such as getting a refund or a replacement) and the number of known incidents or injuries. These products included a whistling kettle made of glass that could break and unleash scalding water, a metal chair that could bend and cause someone to fall and a faulty slingshot that left one person with facial fractures and another with bruises.

With some products, companies put a recall in motion before any injuries have been reported. In August, the CPSC announced Tippmann Sports’ recall of two versions of paintball guns available only at rental facilities. The reason? The trigger safety can fail, allowing paintballs to fire unexpectedly. Tippmann had received reports of three incidents. No injuries.

Given the CPSC’s powers, there’s an old saying among gun control advocates that teddy bears are more regulated than guns. The agency’s authority over toy guns, air rifles and paintball guns presents another long-running irony. Of course, the politics of paintball guns and firearms are very different. Four decades ago, the concept of the government overseeing the safety features of firearms galvanized NRA members and gun control advocates alike.

It started subtly. In 1972, Congress was prepping the law to create the first-ever CPSC, following a Ralph Nader-inspired national study of 30,000 products. The legislation had an advocate in Rep. John Dingell, the Michigan Democrat who retired this year as the longest-serving member of Congress. Dingell was also an NRA board member at the time, and he voted steadily in favor of the NRA’s positions throughout his career. When the CPSC bill came through the House, Dingell offered an amendment with an exemption for products subject to Section 4181 of the tax code — that is, guns and ammunition.

But when a group called the Committee for Handgun Control Inc. later petitioned the CPSC to restrict handgun ammunition under the Federal Hazardous Substances Act, a public furor ensued, with letters pouring into the commission decrying any such ban. In 1975, Sen. James McClure, an Idaho Republican, with help from the NRA, built momentum to pass a new amendment to expressly forbid the CPSC from regulating either firearms or ammunition.

“The NRA was able to generate bipartisan support for the amendment by mailing NRA members and organizing a formidable congressional grassroots mail campaign,” according to a 2005 report on gun product safety that was co-written by a former gun industry lobbyist and published by the Consumer Federation of America. “This effort became the model that has been used by the NRA over the years to kill many gun violence prevention measures.”

As the former communications director for the NRA's lobbying arm, James O.E. Norell, once put it: “The battle was the NRA Institute for Legislative Action’s baptism by fire.” The product safety skirmish epitomized what writer Osha Gray Davidson, author of a history of the NRA, has called the NRA’s “slippery slope” mentality — the position that any regulation whatsoever could lead to outright gun bans and confiscation.

Gun control advocates, for their part, have since divided opinionwise on the right approach to take. This year, for example, Rep. Robin Kelly, an Illinois Democrat, proposed a bill to give the CPSC oversight for guns — similar to other proposals that have popped up over the years. Others, such as the Violence Policy Center, favor product oversight within the Justice Department, voicing concerns that the CPSC isn’t equipped to regulate gun safety and that gun lobby politics would suffocate the commission’s work.

Of course, the CPSC’s safety net doesn’t catch every potentially dangerous product the agency oversees. Ditto for the Food and Drug Administration, which possesses similar authority for medicines and medical devices, and for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which has jurisdiction for automobile safety. Yet these agencies operate as public health “surveillance systems” and serve an important role in the marketplace. They backstop products that can hurt people and create a financial disincentive for unsafe designs.

The key to reducing injuries associated with a product often lies in changing the design, not trying to change human behavior, according to David Hemenway, who directs the Harvard Injury Control Research Center and studies firearm fatalities among children. “You try to create systems where it’s hard to make errors and it’s hard to behave inappropriately,” he says.

Car manufacturers, for example, fought the installation of airbags for years. Today they are part of a constellation of improved safety features that have reduced accident fatality rates.

The fact that guns are inherently lethal doesn’t mean they can’t be designed to lessen the odds that someone will get hurt, or die, unintentionally. For one thing, “guns shouldn’t be involved in drop-fires,” says Stephen Teret, director of the Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Johns Hopkins University. That is an example of a “discreet design defect,” he says.

Another such design defect, in Teret’s opinion, is the absence of an indicator that tells you whether a gun is loaded with a round in the chamber. “The technology has been around for more than a century and would cost less than $1,” Teret says. “And that would save lives.” That's also the case with magazine disconnect devices, which prevent a gun from firing once the magazine is removed, even if there is a bullet left in the chamber.

“But the manufacturers don’t do that,” Teret says, “which raises the question: Why? One of the answers is, we as a society don’t force them to do that.”

'Who Shot You?'

The first case plaintiff's attorneys know of involving Taurus over a drop-fire incident got its start on Valentine's Day in 2005, when Adam Maroney got a call from his dad, Rodney. The father and son ran a business together, a tanning and video rental shop in Boaz, Alabama. Adam, 23 years old at the time, had gone into the store the day before to pick up the cash from the till.

Rodney wasn’t calling about the store. He was calling about a doghouse. Some children in his neighborhood had found three stray puppies and asked Rodney if he’d take one of them. He knew his son had a small, igloo-shaped doghouse. Could he bring it by? Adam said he’d bring it to the store. He put the money bag and his computer in the truck. His Taurus PT 111 was in its holster, with the safety on, in his back pocket — the same way he’d been carrying the Taurus for the eight months since he’d bought it.

When Adam reached over the back of the pickup to put the doghouse in the truck, he heard a loud noise and felt a lot of pain, according to his courtroom testimony. He’d been shot. He managed to get back inside the house and, in a panic, tried calling his dad a couple of times. Adam couldn’t get through to him at first. He called 911, made it to the kitchen and fell to the floor.

Finally, Adam got through to his father. “He said, 'I’ve been shot,'” Rodney said on the stand. “The first thing that came to mind, I thought: 'Well, who shot you?' I said, 'Who shot you?' He said, 'Nobody, daddy.' He said, 'My gun fell out of my pocket and shot me.'”

When Rodney sped to his son’s house, he found him on the floor, clutching his cell phone in one hand and the landline in the other. “He looked up at me and he said, 'Daddy, do you think I’m going to die?' And I said, 'No, son. You’re not going to die. You’re going to be OK.'"

The paramedics rushed Adam about a quarter mile up the street to his church, where they met the helicopter that ferried him to Huntsville Hospital. The bullet damaged his pancreas, destroyed his spleen and entered and exited his left lung, which collapsed, and finally stopped in his chest cavity. He stayed in the hospital for seven days. For months afterwards, he wore drains on his side to catch the fluids coming out of his pancreas.

Adam sued Taurus for violation of state product liability law and for failure to warn in a case that went before a jury in October 2009. Taurus’ defense team argued that Adam wouldn’t have gotten hurt if he hadn’t been carrying a bullet in the chamber in the first place. The company’s lawyers also questioned why Adam didn’t hang on to the bullet that shot him; there was no way to match it with the Taurus gun. Adam told the jury that he hadn’t been thinking about filing a lawsuit while he was in the hospital. “I was barely conscious for most of that time,” he said. “And the times that I was, I was basically just hoping I would live.”

Over the course of the trial, the jury heard from three expert witnesses on guns. Two testified for the plaintiff: John T. Butters, an electrical and mechanical engineer who lived outside San Antonio, and Joe Saloom, an Alabama lawyer and a former firearms examiner for the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences. Butters tried to get the gun to fire by hitting it with a rubber mallet. He couldn’t do it.

But Saloom, who employed what’s known as a drop test, did. He testified that when he dropped the pistol on the ground roughly 20 times, it discharged an empty shell casing four times. To illustrate the effect on video, Saloom put a piece of paper towel in the barrel of the gun. When the gun discharged, it ejected the paper towel, marked with soot from the explosion made by the firing pin coming into contact with the primer — the tiny piece of explosive tucked in the bottom of the shell casing that normally ignites the gunpowder in a live round.

As for the internal safety mechanism in the gun, Saloom told the court: “It does not work like it’s designed to work.”

Some experts argue there’s another way for a gun to fail a drop test, even if a bullet doesn’t fire: if the firing pin, or striker, comes into contact with part of the bullet and leaves an indentation, which shows the safety mechanism isn’t doing its job. This happened in several of Saloom’s drops — and is exactly what happened when the defense’s own expert, James Hutton, dropped a PT 111, muzzle-down, on video.

On Oct. 15, 2009, the jury returned its verdict: $1.25 million for Adam Maroney, including $750,000 in punitive damages. After an attorney for Taurus told a local paper that his client would appeal the decision, the parties reached a confidential settlement out of court.

Five weeks later, Judy Price took her PT 140 to the gun range to practice shooting with her church security group. Two days after that was when the ambulance came to her home and the paramedics whisked her outside naked, her new green sweat suit cut away. And then for nine days she was out cold — a sleep filled with panicky dreams, recitations of the Lord’s Prayer and the sound of bomb explosions echoing in her subconscious. When she awoke at last, she discovered the source of the loud booms: It was the heavy door of the trauma unit banging closed.

One in the Chamber

Price has been around guns her whole life. Growing up in New Jersey, her family occasionally pulled out a .22-caliber rifle to shoot at tin can targets. When her first husband, a corrections officer, went shooting, she’d accompany him. After they divorced, she started dating Paul, a tall, laconic former policeman 21 years her senior. They met when they were both working at Picatinny Arsenal, a U.S. military research center for weapons and ammunition, and wed in 1989.

Paul had always kept his old policeman’s service revolver and a hunting rifle in the house. The two got more serious about guns after they moved to Virginia in 1993 and decided to apply for concealed-carry permits. Paul was traveling a lot for work, and they lived in the woodsy environs of a town outside the Marine Corps base at Quantico. Their thinking at the time: You never know what could happen.

The year of Price’s accident, the two renewed their vows in honor of their 20th anniversary and celebrated afterward at their favorite Mexican restaurant.

Taurus’ settlement with Price didn’t include a confidentiality agreement that would prevent her from speaking out about what happened to her. Friendly and talkative, she says she tells “anyone who’ll listen” about Taurus.

Before she went to a gun show to hand out flyers for the first time, Price checked with the police. She wanted to make sure she couldn’t get arrested. They told her as long as she remained out front and didn’t go inside onto private property, she’d be fine. She made color copies of the flyers for maximum effect.

Price's verbal pitch had to be quick and snappy as her target audience streamed past, eager to go shopping at the expos in New Mexico or Mesa, Arizona. “In two minutes you gotta sell your whole self, because they’re waiting to get into the gun show.”

Each piece of paper carried a photo of her in bra and underwear, her stomach bulging with two red masses — one the shape of a football, where the doctors had cut from her chest to below her belly button, covered her insides with mesh and then left open for about seven months before they could attempt to close it. The other was a knob protruding out from her small intestine, where Price wore the ileostomy bag that collected her waste.

"This is a picture of me,” she’d say, “I want you to know the PT 140 is not safe.” Some people would stop and listen. Some didn’t care. Some were nice. “Nobody was ever really mean,” Judy says, sitting at Paul’s desk in his office, still dressed in the jeans and loose sweatshirt she wore to the gun range that morning. It was a sunny October weekend, clear and crisp in Albuquerque, with the leaves just starting to change color. Russian sage bloomed purple in the backyard. “They’re only mean on the computer because they can’t face me.”

Price has had to work at crafting her message; she didn’t want it to come across as a tale of personal woe but rather as a vivid warning to others. “Am I mad at Taurus? Yeah,” she says, because “if you have that information, you don’t hide it.” However, as the messenger who’s been shot, Price doesn’t always get a warm reception. Given the online heckling she has faced, Price suspects other gun owners are reluctant to come forward about unintended drop fires. Some commenting online have called her a variety of expletives and a moron. She’s been criticized for carrying her gun, just like Adam Maroney, with a bullet in the chamber.

Even Price's own sense of embarrassment and self-doubt bothered her for months after her accident: She was a general’s secretary with top secret security clearance. She threw picture-perfect dinner parties. She poured herself into the upkeep of a tidy and bountiful garden. She prided herself on being hardworking, detail-oriented, physically fit and knowing how to handle a gun. Even though she knew the incident wasn’t her fault, it took a while for it to sink in that the gun had malfunctioned.

The Taurus PT 140, when Price encountered it at an Albuquerque gun show, held manifold appeal. The gun was easy to grip and rack. According to Paul’s research at the time, it was certified for sale in California, meaning it had passed the state’s drop test. (California, New York and Massachusetts are the only three states that require drop testing on guns.)

Making her case at gun shows didn’t feel like enough for Price. So in 2011 she hired someone to build her website, where she featured updates on the surgeries she still had left to go and an account of what happened to her. The site’s traffic varied. Some months it was zero visitors, others 30 hits or even 100. Two people contacted her who said they, too, had been shot with drop fires from Taurus guns. Both were in law enforcement. One of them she still keeps in touch with, a camaraderie she likens to connecting with a friend at a high school reunion: someone who knows what you’ve been through. Last summer, though, Price decided it was time to take down the website.

Adrenaline Shot

On a summer evening in July 2013, 24-year-old Chris Carter waited in an unmarked police car in East Moline, Illinois, supervising an undercover crack cocaine bust. The former college football player had landed a job with the Scott County, Iowa, sheriff’s office, and from there won a spot in the Quad City Metropolitan Enforcement Group (QCMEG), a narcotics unit that straddles Iowa and Illinois. He loved the fast-paced work of hand-to-hand drug buys and the adrenaline rush that came with it. After two years working undercover, he was promoted to supervisor.

With the exception of what happened the day his gun went off, serving in the unit was the highlight of Carter’s budding career in law enforcement. The gun was a Taurus PT 140, the same model Judy Price had owned. Carter’s dad, a police officer and a farmer in Illinois, gave it to him for Christmas in 2009. Since Carter’s department-issued service weapon was too big to conceal under his clothes, he used his Taurus for QCMEG operations. Police departments all across the country commonly allow officers to use approved personal weapons in some capacity, whether on the job or off-duty.

“I wasn’t familiar with the gun having a malfunction or I never would have been carrying it.”

As a suspect arrived on-scene riding a bicycle, Carter followed him in his car to an alleyway and then began to pursue him on foot. As he ran after the suspect, Carter’s gun broke loose from its holster, fell and fired, according to his deposition testimony. He says he didn’t even realize the shot came from his gun until he saw it lying on the ground.

“After it occurred, my first thought was, I heard kids in a backyard nearby,” Carter tells IBT, “and when it happened, I heard them scream. That was my first concern.”

The suspect fled on his bicycle, only to be apprehended nearby. Carter says he immediately secured the gun and spoke with some people who came out to the alley. They told him no one had been hurt. Carter contacted both 911 and the East Moline patrol sergeant to report the incident.

But he wondered, what exactly happened? “I wasn’t familiar with the gun having a malfunction or I never would have been carrying it,” he says. Back in the car, Carter examined the gun. He had to take the safety off to manually eject the spent casing that was still inside the chamber.

A week later, the police got a call from someone who’d been out of town and returned to find their car window shot out. The police investigated. “I believe they matched [the bullet] up with my weapon,” Carter says. The Illinois State Police launched their own internal investigation, and Carter answered questions for one of their detectives. “There was nothing I felt I had done that caused it,” he says.

'I Trusted You'

The church the Prices attend sits on an 11-acre leafy campus facing the Sandia mountains. The Prices take the safety ministry seriously; even when they pack up and go to Mesa, Arizona, for the colder months, they come back here for their monthly rotation. A security shift entails either patrolling the grounds, where the sermon rings out on loudspeakers, or sitting inside a cavernous, 2,000-seat auditorium.

Price’s faith deepened after her accident. “The accident showed me how faithful God is, what a wonderful husband and family I have, and that you can’t give up,” she says.

She pulls up the video of her story and plays it on her desktop computer. There are moments on camera when Paul chokes up about how he never got to say goodbye to his wife before the ambulance whisked her away, and when Price herself wonders aloud if, after all her surgeries, a buildup of scar tissue over time will cut her own life short. “I trusted you with a product,” she says in a direct appeal to Taurus on camera.

Her anger with the company is not to be confused with a core belief she still holds true: People should be able to own guns. Carrying one makes her feel “more empowered, that I don’t have to be a victim.”

Guns could be made better. “I’m not trying to limit people having guns,” she says. However, she adds, “I certainly don’t mind if guns went under a better review and testing. I’m all for more testing and things like that — that doesn’t mean it’s not still coming out.”

Paul comes to the door of the office and asks Judy if she’s ready to go check on the bees — a ritual of the beekeeping hobby they took up this year. For the rest of the afternoon, until it’s time to go to church services, they show off the hive they’d built in the backyard and offer a demonstration of the workshop machinery where Paul makes his own bullets, filling discarded casings from the range with gunpowder. Judy makes snacks of apples and peanut butter that she sets out on the patio while she talks some more about finding her way to the megachurch where she feels she has developed a true relationship with God for the first time in her life and where she feels she can best be of service on the safety ministry.

Judy and her husband go back to their room to get changed, and come back out wearing matching dark polo shirts, loose-fitting and covering their guns. She lifts the bottom of her shirt a moment to reveal the holster in her waistband, snug against her scarred belly.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.