California Marijuana Legalization 2016: Growers And Officials Struggle Over Making Pot Farms Environmentally Friendly

ARCATA, California – From the air, the so-called Emerald Triangle looks disconcertingly yellow. Such is the view as pilot Mark Harris tilts his 1957 Cessna 182 at a dizzying angle to get a better view of the rolling California landscape stretching below him.

Harris, an Arcata attorney, often uses his single-prop plane to hop from one county courthouse to the next. But today he’s getting a bird’s eye view of the marijuana farms that dot the forested hills around Upper Redwood Creek in Humboldt County, an area that’s part of the three-county Emerald Triangle region known far and wide for the quantity and quality of its marijuana.

The farms are easy to spot: In clearing after clearing among the trees, dozens of dark green spots, each representing a marijuana plant that’s nearly ready to be harvested, are arranged in tidy rows. But the flight also highlights in stark terms the ecological consequences of such endeavors. The rolling hills in all directions are dusty and parched. And at the base of the hills, curving this way and that, flows the Upper Redwood Creek -- or what is left of it. Thin ribbons of water meander past silt-clogged riverbanks, a far cry from the healthy waterway that once flowed through the area.

The environmental impact of marijuana farms in an area already struggling with prolonged drought and a fragile ecosystem has become a major issue for law enforcement, regulators and industry stakeholders alike. Concern over watersheds and wildlife has become the driving force behind large-scale marijuana raids in Northern California. A blue ribbon commission on marijuana policy helmed by California Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, a former mayor of San Francisco, recently concluded a main goal of any 2016 legalization effort should be to reduce the ecological harms of illegal marijuana cultivation. And recently passed statewide medical marijuana regulations set new environmental standards for marijuana operations. But are the thousands of small-scale marijuana grows really wreaking ecological havoc in the Emerald Triangle? And if they are, is it possible to rein in these farms’ water use and environmental impacts -- or is the world of backwoods marijuana grows in Northern California simply unsustainable?

Rivers Running Dry

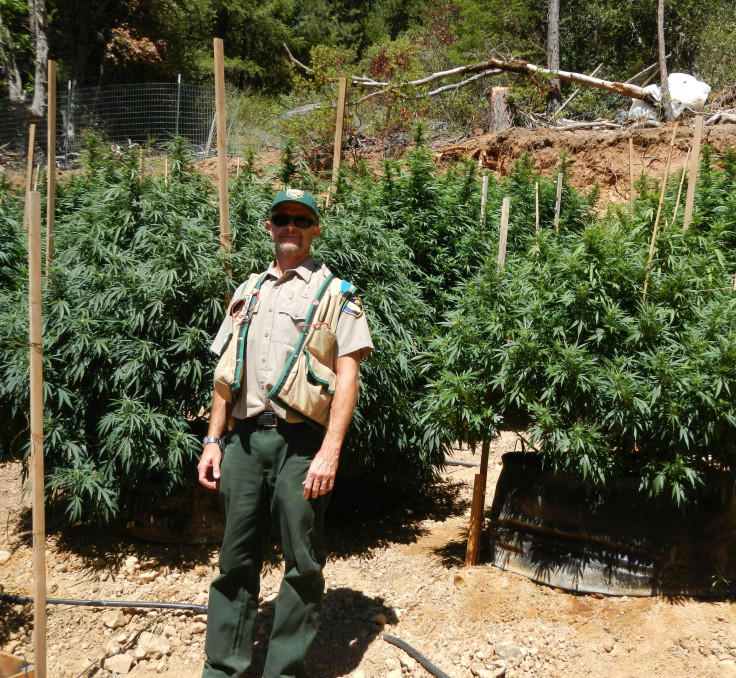

Among the major concerns are the environmentally damaging procedures some cultivators follow to grow as much marijuana as quickly and quietly as possible in the wilderness: using dangerous herbicides that leach into the groundwater; employing toxic rodenticides to keep away wood rats but that also kill other native animals, such as Pacific fishers, black bears and northern spotted owls; running leaky, inefficient diesel generators to power clandestine indoor grow rooms; and bulldozing forest lands and building illegal roads to create grow sites, leading to debilitating erosion, then leaving behind trash and waste once the plants are harvested.

All of this is occurring in a region that already faces its fair share of ecological hardships. Northern California, home to some of the world’s largest remaining redwood stands, lost most of its old-growth forests over the last century to the logging industry, leading to large-scale erosion and younger-generation trees that are thirsty for water.

“It’s pretty tragic,” says Jennifer Carah, an ecologist at the Nature Conservancy who was lead author of an article published this summer in the journal Bioscience that detailed the environmental costs of marijuana grows. “It’s a very big problem, and we can’t afford to continue to ignore the environmental impacts of this industry.”

Some marijuana growers in the region argue that the most glaring examples of ecological devastation are due to a few bad actors, those who set up trespass grows in the area’s ample national forest lands or folks who aim to make as much money as possible in a season or two. They say the Emerald Triangle’s longtime growers, the second- and third-generation marijuana farmers who’ve been tending the same lots for decades, take a more careful approach to cultivation.

Still, responsible farmers and bad actors alike share responsibility for what could be the biggest environmental problem related to marijuana grows in the region: what these operations are doing to local streams and rivers. Harris argues that the demands of small-scale marijuana farms don’t compare to the sort of water consumption associated with massive California farming operations like alfalfa farms, rice fields and fruit and nut orchards. “The enemy of the environment is large-scale agriculture,” he says. “These farms are literally a drop in the bucket relative to Big Ag.”

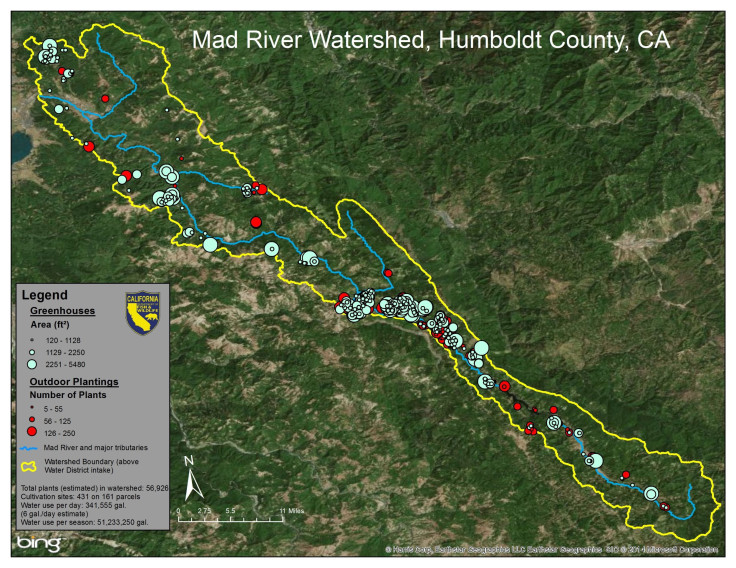

Scott Bauer, a biologist with the state Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), argues to the contrary. With tens of thousands of marijuana plants in the Emerald Triangle region alone, Bauer says, the water use adds up. “We are talking about a huge influx of people coming here in the last 10 years to cultivate marijuana,” he says. “The landscape has never seen this level of agricultural use. There was never anyone out here growing agriculture in the forested lands of Northern California.”

To calculate the effects of all these new agricultural operations, Bauer and his colleagues scrutinized high-resolution aerial photographs of four river systems in the Emerald Triangle, tallying the number of indoor and outdoor grows they could identify in the regions around the waterways. They concluded the total number of marijuana plants in each of the four areas ranged from 23,000 to 32,000. Then, using a 2010 estimate from the Humboldt Growers Association that a typical marijuana plant requires six gallons of water a day from June through October, they calculated the total amount of water these plants required. They found that in three of the four areas, water demands for marijuana cultivation greatly exceeded minimum summer stream flows. Only along the Upper Redwood Creek -- the area over which Harris flew his Cessna -- did existing marijuana farms not risk sucking all the local streams dry.

The risk isn’t just depleted waterways; local wildlife could be in danger. All four regions studied by Bauer and his colleagues, for example, are populated by California coho salmon, a threatened species whose population has dropped precipitously since the 1940s.

But many in the marijuana industry contest the water-use estimate that underlies such dire conclusions. They question the idea that a typical marijuana plant requires six gallons of water a day -- that would make it twice as water-intensive as the wine grapes grown in the region and roughly as thirsty as almonds, a crop that’s been demonized as a major culprit in California’s drought. “In 2010, [the 6-gallons-per-plant-per-day estimate] was a number that reflected the limited understanding and information that we had,” says Hezekiah Allen, executive director of the California Growers Association (CGA), a trade group for local marijuana farmers. “Now we can start to do some more dynamic estimates.” These days, the CGA prefers an estimate that roughly equates to 2 gallons per plant per day -- slightly more water than a typical toilet consumes per flush.

A Stab At Regulation

No matter how much water the average marijuana plant in the region requires, state officials and industry representatives agree that something needs to be done to make sure marijuana farmers aren’t causing excessive environmental damage. Bauer estimates that less than 5 percent of marijuana growers in the region have the correct state permits to divert the water they’re using. That makes sense, considering many farmers are reluctant to go public about their marijuana operations, for fear of state and federal crackdowns.

Thanks to a new cross-agency Watershed Enforcement Team, the CDFW can now fine growers directly for illegal water diversions and water pollution, rather than go through district attorneys, as they had to in the past. But the department is chronically short-staffed and underfunded -- “We have five game wardens, two scientists and one lawyer working on regulating the industry,” Bauer says -- not to mention ill-prepared to handle the sort of security operations that can accompany major illegal grows. Plus, confrontational approaches such as raids and fines could make the problem worse, forcing growers further into the backwoods and legal shadows, where they are apt to use any cultivation technique necessary to score profits before they’re at risk of being busted.

To complement these new enforcement tools, the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, which oversees water quality in the region, turned heads this summer by announcing a bold new program: the state’s first water-use regulations designed specifically for cannabis cultivators. Starting in February 2016, farmers with marijuana grows of 2,000 square feet or more will have to enroll in the program, which will require them to have proper water diversion permits for their grows and address issues such as erosion control, irrigation runoff, off-season water storage and environmental cleanup. Fees funding the program will be based on the severity of environmental damage at each grow.

In return, farmers will be offered an opportunity to fix problems without the immediate threat of raids or fines, although after an extended grace period, those who are still noncompliant will face financial penalties. The idea is to turn the marijuana farmers into the environmental stewards of the region, because they’re the ones with the income and incentive to protect the land for generations to come. The fact that the substance at the center of the regulations is still federally illegal is being conveniently overlooked.

“I think it is one of the most innovative, collaborative, sustainable initiatives, not just in this industry, but really in the state,” the CGA’s Allen says. “They did a really good job giving it the teeth it needed, but still making it approachable.” The program gained more teeth courtesy of the state’s new medical marijuana regulations, passed last month. To receive business licenses from the state’s new Bureau of Medical Marijuana Regulation, farmers will have to comply with all existing laws and regulations, including the water board’s new program. What’s more, the new laws will regulate marijuana pesticide use, set organic standards for the industry and make permanent the pilot watershed enforcement program that led to the water quality control board’s pioneering water-use regulations.

Still, it’s unclear whether such efforts will be enough. While Carah at the Nature Conservancy estimates it will take roughly $100 million to $120 million a year in statewide funding revenue to prevent and repair environmental impacts associated with marijuana farms, the state’s new medical marijuana laws don’t dedicate any funding at all to the issue.

There’s another lingering concern: Even with adequate funding and industry buy-in, such efforts could be too little, too late. The current extent of marijuana cultivation in the Emerald Triangle, even properly regulated, may well prove to be more than the region’s limited natural resources can handle.

“It’s the big question of the day,” Bauer at the Department of Fish and Wildlife says. “People are trying to obtain permits, people are capturing interim water and trying to do all the right things. But at some point in any given watershed, all of the water will be accounted for. In these watersheds, where streams are drying up on a yearly basis, something needs to be fixed. There is a long way to go until we achieve sustainability.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.