California's Brown Losing Favor As Budget Talks Draw Closer

At the beginning of 2013, Californians couldn’t stop singing Gov. Jerry Brown’s praises. But now, just a few months later, Brown seems headed for a crash on the rocks.

With the state budget deadline looming ever closer, Brown proposed a deal including healthcare cuts so wildly unpopular that insurers, doctors and union leaders -- groups that are typically, and notoriously, at odds with one another -- have formed a coalition to fight them.

The coalition, dubbed “We Care for California,” visited the state capitol on May 1 to show its support for Senate and Assembly bills that would reverse Brown’s cuts. (Yes, both branches of the state legislature oppose them, too.)

What makes the coalition’s efforts to fight the governor even more striking is that many of its members have been his biggest financial supporters. According to FollowTheMoney.org, the California Medical Association and California Dental Association each gave more than $1 million to Brown’s campaign to pass Proposition 30, a plan to raise Californians’ taxes in hopes of bringing in another $6 billion in annual revenue. The California Hospital Association gave $2 million to the campaign.

Now?

“We are fighting these cuts on all fronts,” Jan Emerson-Shea, spokeswoman for the California Hospital Association, said. “We’re fighting them in the courts, we’re fighting them in the legislature, we’re going to be fighting it when it comes to the budget discussions.”

In February, Brown enjoyed the highest approval rating of his career. At a conference on education in January, John Myers of News 10 ABC Sacramento declared that the governor “has more political capital than anyone.”

Brown has also faced backlash on his education proposal, which takes money from suburban schools and gives it to urban ones.

This plan has generated protests from not only those school districts it would hurt -- Anaheim, Capistrano, Chino, Chula Vista, Glendale, Irvine, Montebello, Mt. Diablo, Placentia-Yorba Linda, Pomona, Poway, Saddleback, San Jose, San Ramon Valley, Temecula and Torrance, according to the Los Angeles Times -- but also the governor’s own party. Senate Democrats have already offered their own version.

But the disappointment doesn’t stop there. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered California to cut its prison population to about 110,000 by June 2012. Brown thought he had this covered by shifting about 25,000 low-level inmates to local jails. He thought this would be fine, that the courts would understand, even though the prisons were still 10,000 inmates over capacity. But he was overconfident; early in April, a panel on the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously ruled against him, stating he must comply. He needs to reduce the prison population by 10,000 within a month -- and he has admitted to having no plan for doing so other than just letting them loose.

“We certainly will appeal whatever we can appeal,” he told reporters while in Shenzhen last month. “But at the same time, with the court threatening contempt at every level, when the Supreme Court gives these three judges the green light, then we have to do what they tell us, and we’ll have a list of 9,000 or 10,000 of our finer inmates that will be ready for neighborhood visitations throughout California. We’re going to try to find the nicest of the nice, but I have to tell you, it’s harder to get into prison now, there’s not as many people hanging around.”

Yikes.

And to top things off, the governor’s beloved bullet train seems to be going nowhere fast. Construction was supposed to start in July, already a six-month delay from the initial date. But last week, one of the groups that had previously been most cooperative with the project threatened to pull the plug. Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway Co. sent a letter warning that no deal has been reached to build anything on their track and that it may not be willing to accept Brown’s proposal.

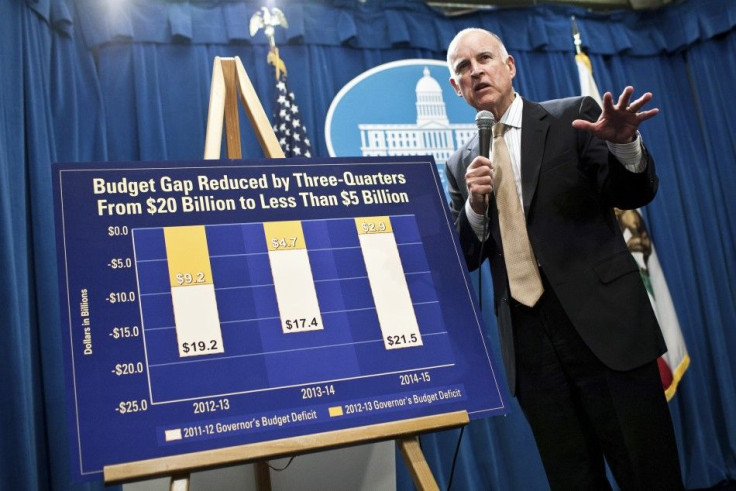

Although a personal victory for the governor, Proposition 30 can’t solve all of the state’s problems. As it becomes clearer and clearer that the state still doesn’t have enough money to pay its bills, Gov. Brown’s political capital will run out.

Katherine Timpf is a Robert Novak Fellow with the Phillips Foundation and a reporter at Campus Reform.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.