Cancer-Detecting Pen Can Reveal Disease Within 20 Seconds During Surgery, Researchers Say

Researchers from the University of Texas on Monday revealed they've created a pen with technology that could diagnose different types of cancer within a matter of seconds.

At a South By Southwest (SXSW) conference, the researchers unveiled a previously discussed device called The MasSpec Pen, which they claim can show evidence of cancer tissue just moments into surgery. Tests published in the journal “Science Translational Medicine” in September touted that the MasSpec Pen has a 96 percent accuracy rate.

The MasSpec Pen is an "automated and biocompatible handheld mass spectrometry device for rapid and non-destructive diagnosis of human cancer tissues," according to the research group’s website.

The pen reportedly utilizes touch technology to find the disease. The tool "enables controlled and automated delivery of a discrete water droplet to a tissue surface for efficient extraction of biomolecules," which goes through a "mass spectrometer" for molecular analysis, the site read.

"Then, we can create a molecular fingerprint that can say if this is cancer or if it’s not based on the molecules of the pen," said Marta Sans, graduate research assistant for the Livia Eberlin Research Group in Austin, Texas.

The pen can detect four types of cancer including ovarian, lung and thyroid.

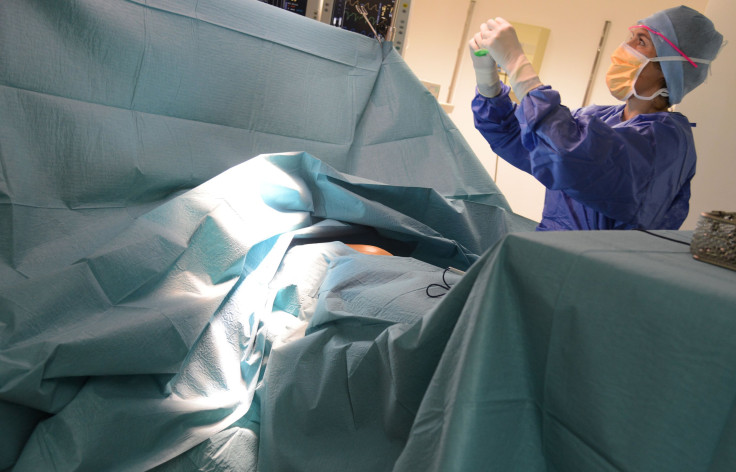

Experts said the technology could revolutionize the way surgeons distinguish cancerous tissue from healthy tissue, which can be problematic during surgery.

The tissue is then sent to be observed by a pathologist, often a lengthy process, according to Dr. Leonard Lichtenfeld, Deputy Chief Medical Officer for the American Cancer Society.

Litchfield added that researchers must continue to test the pen’s accuracy. Meanwhile, scientists have yet to use the device on human tissue during surgery. The Food and Drug Administration must also authorize the pen, a process that could take years.

"We have to remember that it’s a long way from concept, to proving it really works, to get it used by doctors in real life. We don’t know the answer to that yet and, clearly, the researchers understand that they have more work to do," Litchfield said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.