Car Cybersecurity: Developers Say Automakers Should Engage With Ethical Hackers And Learn From Tesla, GM

After Troy Hunt recently discovered how easy it is to remotely hack a Nissan Leaf electric car though its car-control mobile app, he quickly alerted Nissan to the problem.

Using little more than the internet and some basic coding knowledge, the Sydney-based software security expert was able to activate the climate controls of a Leaf that a colleague in the U.K. owned. A few more taps on a keyboard from 10,000 miles away, and Hunt had extracted data exposing the car's travel times and distances, compromising the privacy of the vehicle's owner.

As a member of the ethical hacking community, Hunt wanted Nissan to fix the app problem before malicious hackers caught wind of the vulnerability. But because Nissan, unlike many tech-industry companies, doesn't have a formal bug-reporting process, he wasn’t sure what was the right way to go about reporting the issue. So he reached out to members of his tech-savvy network.

“I asked on Twitter if anyone had a security contact at Nissan, and I got a couple of quick replies,” Troy said in an email to International Business Times. “I had no trouble getting in touch with them by leveraging my social network.”

Thirty-two days passed, and the vulnerability in NissanConnect EV lingered. Finally, after Hunt said Nissan wanted “weeks” longer to investigate the problem, he decided a little public shaming was in order. Just two days after he posted a detailed outline of the software vulnerability on his website in late February, Nissan disabled the app and said a more secure version would soon be released.

As cars become more connected to the Internet and cellular networks, auto manufacturers are quickly learning they need to engage with ethical hackers to better understand the vulnerabilities of their cars, and they're finally beginning to look to Silicon Valley for guidance.

Almost a year after noted American white-hatters Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek showed they could remotely take over controls of a Jeep Cherokee, spurring a massive recall, almost all car companies still lack formal software-vulnerability reporting policies. These so-called bug-bounty programs have improved the cybersecurity of everything from cell phones to banking networks.

“Car manufacturers don’t have enough security experts,” said Chris Eng, head of research at Veracode, a Massachusetts-based application security developer that recently called on the auto industry to improve its cybersecurity strategies. “They’re just now figuring out there are so many ways to compromise a system.”

Eng and others say the auto industry needs better engagement with the hacking community as cybersecurity concerns mount.

“Many in the automotive industry really don’t understand the implications of moving to this new computer-based era,” U.S. Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.), a member of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, said at a connected car expo in January. “We anticipate the hacking to continue in 2016, since there is no good security practice in place.”

Car buyers want the connected features that are appearing in more cars these days, including software that controls safety-critical functions like adaptive cruise control and sensor-dependent collision-avoidance systems.

But many of these features require data transfers between car components that have access to the internet and telecommunications networks and the software that controls stuff like brakes, steering, ignition and door controls. For example, a car’s infotainment unit needs access to steering inputs to display parking-assist guides on the dashboard screen. And as Nissan’s Leaf app shows, any software connecting your mobile phone to your car demands super vigilance.

“Once you connect a feature, you now have an attack surface that wasn’t there before,” said Hunt, adding that the platform will attract hackers looking for ways to exploit its vulnerabilities.

Alex Rice, chief technical officer of HackerOne, which provides a social-media-style platform connecting companies to coders, says remotely hacking a vehicle's controls is still difficult. It requires hackers to physically access vehicles to reverse engineer their systems. And these hacks typically only work with specific models or brands whose systems were dissected. “But you can imagine what could have happened if instead of Miller and Valasek working with the automaker to fix the Jeep Cherokee vulnerability they had posted what they learned online for others to duplicate,” Rice said.

The industry is slowly warming to the idea of rolling out the welcome mat to ethical hackers.

Last summer, the Auto Alliance, an industry trade group, established the Information Sharing Analysis Center (ISAC) aimed at bringing together the collective brain power of the world’s top automakers with outside advisers to establish a strategy for fixing connected-car vulnerabilities.

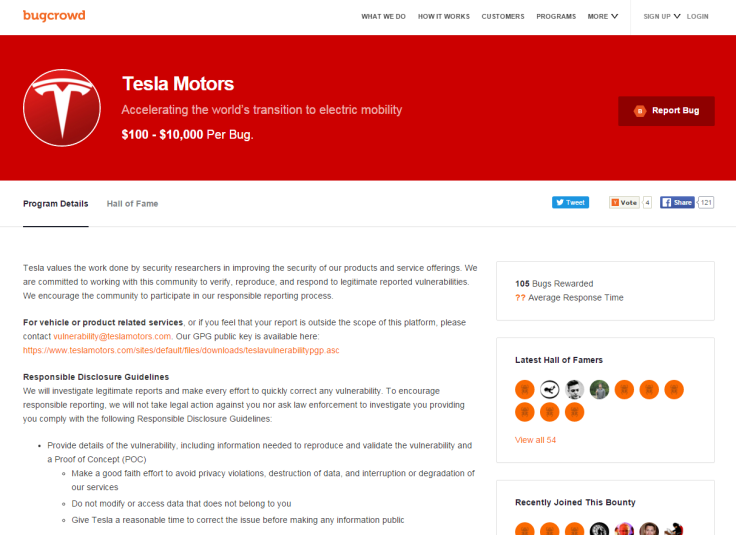

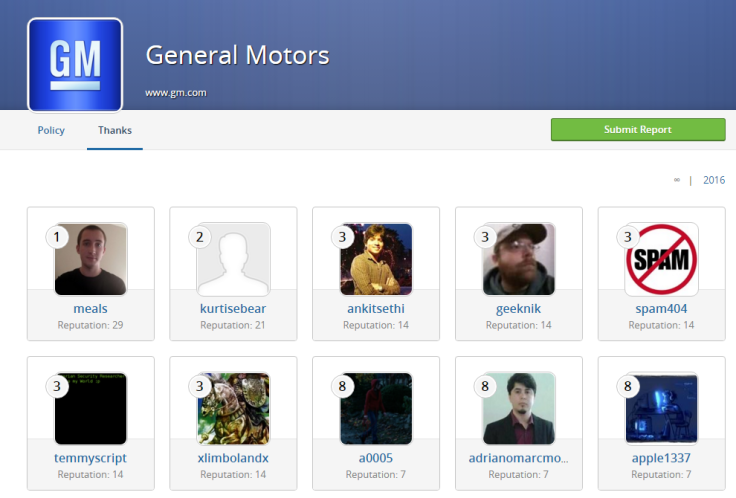

Earlier this year, General Motors became the first major automaker to unveil a software- vulnerability disclosure program, known informally as a "bug bounty" because companies typically offer cash incentives to lure ethical hackers to report bugs and security holes. GM says it plans eventually to offer cash awards — an approach that Tesla Motors adopted last year.

It’s a page right out of the Silicon Valley handbook, where companies like Microsoft and Intel have long courted ethical hackers to help them lock down the attack surfaces in their systems. Google offers a $20,000 bounty to anyone who can remotely take over another user’s Google account. (The company won’t say if anyone has ever done it, but the offer stands.)

“The tech industry has a far more mature approach to collaboration with cybersecurity researchers than most industries,” said Rice, a former head of Facebook’s product security operations. “Even if the automakers work together on safety, there is still a stigma around sharing vulnerability information.”

Through Rice’s HackerOne platform, GM informs software security researchers they are free under certain conditions from legal liability for tinkering with its software. Since the start of the year, GM has received 43 submissions from 10 independent cybersecurity experts located as far away from Detroit as Lagos, Nigeria, and Jaipur, India.

Though he declined to offer details, Jeff Massimilla, GM’s chief product cybersecurity officer, told IBT that the program has already helped GM fix bugs. “We’ve received a handful of very actionable and tangible things within our disclosure program,” he said. “I would not be surprised to see more automakers adopt this better, more defined structure.” Massimilla says GM has a global team of 70 people devoted to cybersecurity.

Other automakers have yet to announce plans to establish similar bug-bounty policies, but Ford said it recently joined ISAC, “which represents the collective nature of automakers' diverse approaches to enhance vehicle security.”

“Ford has long been aware of security threats to connected vehicles and takes cybersecurity very seriously by consistently working to mitigate the risk,” the company said in a statement to IBT. “We focus on security of our customers before the introduction of any new technology feature by instituting policies, procedures and safeguards to help ensure their protection.”

Rooting out software flaws that could compromise the privacy and safety of vehicle occupants is not a selfless task. Automakers have an incentive to guard against attacks that could harm their brands, or even the industry as a whole. New connected car features also allow carmakers to charge a premium, too, which improves profit margins.

A survey of more than 1,100 car shoppers released earlier this month from Kelley Blue Book, the automotive pricing and information provider, found that most people are wary of self-driving cars — vehicles that will require an immense amount of interconnectivity with the surrounding environment. And most survey respondents said they would blame automakers for security breaches even if the attack originated from a plugged-in device, like a mobile phone.

Hacking incidents will make consumers wary of the technology, says Karl Brauer, senior editor for Kelley Blue Book.

“In theory you could actually see a point of time where there’s higher value for preconnected cars,” he said. “It used to be that people didn’t want a lot of electronics in their cars because it was an issue of having more stuff that could break. But we will see a time when people could be adverse because there’s more stuff that could get hacked.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.