Chernobyl Wildlife Thrives Decades After Nuclear Plant Disaster, With 'Humans Out Of The Picture'

For the last 30 years, the 1,600 square mile “exclusion zone” around the Chernobyl nuclear plant has remained free from human interference. The evacuation of nearly 120,000 people from the region after the world’s most disastrous nuclear accident has, it seems, provided wildlife in the region the opportunity to thrive -- turning it into a nature reserve.

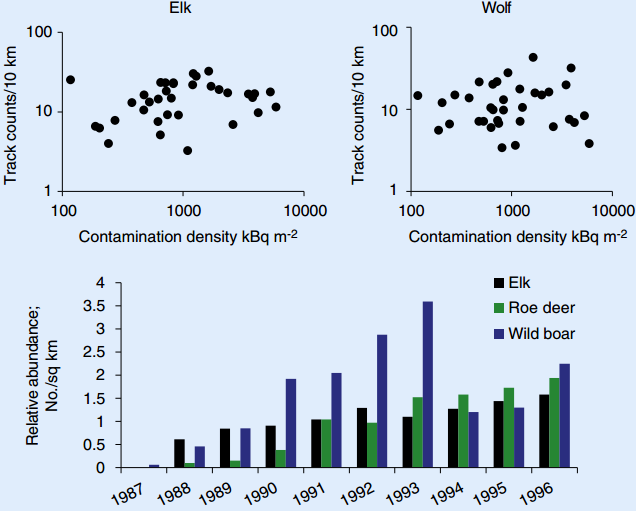

In findings that run counter to previous hypotheses that predicted a drop in animal populations as a result of chronic long-term exposure to damaging radiation, the number of large mammals, including elk, roe deer, red deer, wild boar and wolves, have rebounded, with some of the population levels similar to those in four surrounding uncontaminated nature reserves.

“There have been many reports of abundant wildlife at Chernobyl but this is the first large-scale study to prove how resilient they are,” Jim Smith from the University of Portsmouth, England, who led a team that carried out the census, said in a statement. “We know that radiation can be harmful in very high doses, but research on Chernobyl has shown that it isn’t as harmful as many people think.”

Additionally, the study also underscores the negative impact humans have on wildlife and provides an opportunity to see what happens “when you take humans out of the picture,” Smith told BBC.

The team, which published its findings in the journal Current Biology, found that not only had animal populations rebounded, they were, in all likelihood, much higher than the pre-accident levels. For instance, the number of wolves living in and around the Chernobyl site was found to be more than seven times greater than those in uncontaminated nature reserves.

“This doesn’t mean radiation is good for wildlife,” Smith added. “Just that the effects of human habitation, including hunting, farming and forestry, are a lot worse.”

The study, which includes census data covering 20 times the area of previous studies and an analysis of historical data from aerial surveys of the exclusion zone, also has implications for understanding the long-term impact on wildlife at Fukushima in Japan -- the site of the world’s second-worst nuclear accident.

“Chernobyl caused a lot of human damage. The social and economical problems were huge. If you set that aside -- if you can set that aside -- it’s hard to argue that it’s really damaged the ecosystem as a whole,” Smith told the Guardian.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.