Chicago Kids Back In School, But Issue Of Teacher Evaluations Remains

How do you judge a teacher?

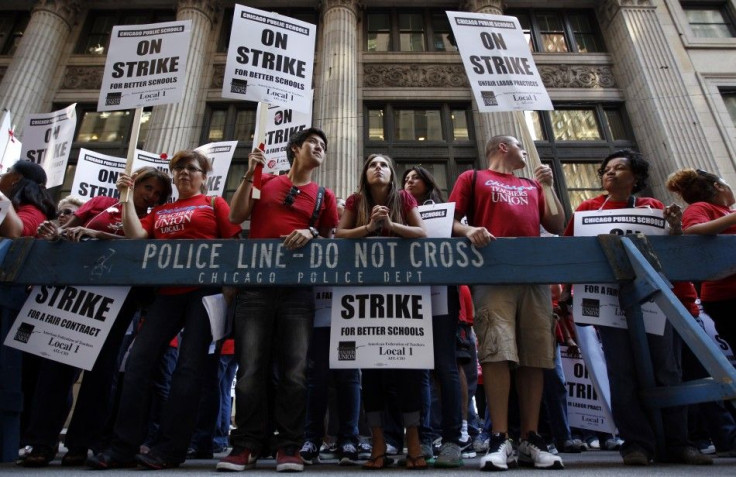

It’s a question that has roiled the national education reform debate, and its contentiousness was on prominent display in the recently resolved teacher strike in Chicago. Teachers on strike were in part pushing back on Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s desire to implement teacher evaluation systems that incorporate, among other factors, student test scores.

For Emanuel and other champions of the education reform movement, holding teachers accountable has become a key way to ensure that students get a quality education. And while models for gauging teachers vary, reformers want to include data on student achievement – namely, evidence that their test scores are improving.

That rankles teachers who think relying on test scores offers an incomplete picture, overemphasizing one rigid measurement to the exclusion of other indicators that students are learning. More importantly, many educators say, impoverished or disadvantaged students are likely to test poorly compared to their better-off peers. Given the wide range of inequality across classrooms, this argument goes, judging teachers by looking to student test scores is tantamount to punishing teachers for having poor students.

“This is no way to measure the effectiveness of an educator", Chicago Teachers Union president Karen Lewis said in a statement released during the strike. “Further there are too many factors beyond our control which impact how well some students perform on standardized tests, such as poverty, exposure to violence, homelessness, hunger and other social issues beyond our control.”

But for proponents of more rigorous evaluations, finding a better way to judge teachers, even if these new methods are in their infancy, is better than a status quo in which the vast majority of teachers are deemed to be acceptable.

“I think we have to look very closely at the systems we’ve had in place up until now which have completely failed to differentiate really outstanding teachers from just average teachers from unacceptably poor teachers," said Sandi Jacobs, vice president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, an organization that advocates for more strenuous teacher evaluations. "So while these new systems may not be perfect, we have to make sure teachers are getting feedback so they can grow and develop and improve, and so we can identify who really great teachers are and who underperformers are.”

The issue is not unique to Chicago. For instance, teacher evaluations were a key sticking point when talks between New York and its teachers unions hit an impasse earlier this year, risking the loss of hundreds of millions of federal education dollars.

The Obama administration has pushed better teacher evaluations in part through a competitive grant program, known as Race to the Top, in which states competed for big chunks of federal money by submitting reform proposals. In pursuit of those federal dollars, Illinois passed a law in 2010, the Performance Evaluation Reform Act, which required schools to factor in student test score progress when they evaluated teachers and principals.

The issue came to a head in Chicago because the 2010 law, while giving most Illinois schools until 2016 to erect new evaluation systems, dictated that some Chicago public schools would implement a new system starting in September of 2012. The Chicago Teachers Union, headed by the fiery Karen Lewis, was not pleased.

The agreement ending the Chicago strike stipulates that student growth measures will account for 30 percent of teacher evaluations – the minimum required under state law – while leaving open the possibility that the school district and the union will later raise the proportion.

But the resolution comes amidst enduring skepticism about the effectiveness of judging teachers based on how their students fare on tests. In March, 88 college professors sent Emanuel a letter warning against rushing to implement new evaluation systems centered around test scores, warning that if Chicago moved too quickly, "we can expect to see a widely flawed system that overwhelms principals and teachers and causes students to suffer."

“We…conclude that hurried implementation of teacher evaluation using student growth will result in inaccurate assessments of our teachers, a demoralized profession, and decreased learning among and harm to the children in our care,” the letter’s authors wrote. “Until student-growth measures are found to be valid and reliable sources of information on teacher or principal performance,” they added, “they should not play a major role in summative ratings.”

So while Chicago students are returning to school, the broader dispute over teacher evaluations is here to stay. The Race to the Top fund is exhausted, but the Obama administration now has a new strategy for advancing its education agenda: it is offering states an exemption from some of the more punitive requirements of the No Child Left Behind education law, but only if states apply for a waiver. In order to obtain that waiver, states must lay out a reform vision – and one of the things that earn them points is to devise and put in place new teacher evaluation systems.

The federal government has yet to formally accept Illinois’ application. But 33 states have applied for No Child Left Behind waivers, and most of them are promising to take on teacher evaluations. Some states have already implemented them, with mixed results.

But while the momentum seems to be in favor of states tightening their teacher evaluation standards, it is still a volatile issue for educators and researchers.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.