Chile Since Pinochet: On The 25th Anniversary Of The Dictator's Ouster, Is He Among The Disappeared?

For Carmen Garfias, the sign that Chile’s military regime, which darkened the country during the 1970s and '80s, was on its way out was not the social upheaval, nor the advanced age of the general, nor even international pressure. For the Chilean-born Florida resident, the first clue was in a song.

“In university, students would be made to sing the national anthem every week,” recalled the 55-year-old expat, who graduated in 1980 when the regime was at its apex. “Students would stay behind, not wanting to go all the way to the first rows in front of the stage. We would sing it in half-hearted voices. There was a resistance, a rejection toward the idea of Chile we were forced to live in.”

Garfias, who was only 15 when Gen. Augusto Pinochet overtook Chile’s government in a 1973 coup, was a fierce opponent of the regime “even before it started,” as she pointed out.

“We knew something was happening then. People were scared -- but brave,” she added.

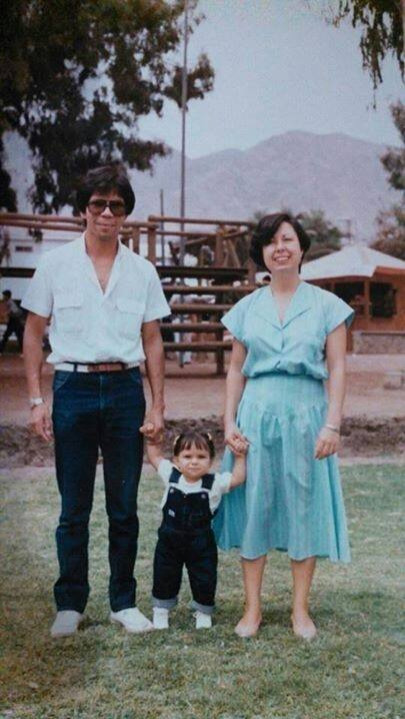

Garfias lived with Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship through her high school and college years, and on to the beginning of her career as a physical therapist. She moved with her family to the U.S. -- first Texas, then Florida -- for work in 1994.

The 1973 coup d’etat that had ended socialist President Salvador Allende’s government, the political terror that reigned in Chile during the 1980s, the plebiscite that brought the Pinochet regime down in 1988 and the restoration of democracy in 1990 -- all are engrained in Garfias' life story, part of the backdrop to events ranging from her high school graduation speech to her wedding and the birth of her two daughters. “Every Chilean life is shaped by the dictatorship,” she said. “Whether you lived through it, or you ran away from it, or you have only heard about it, it is a part of all of us.”

Pinochet’s 17-year long military regime remains one of the bloodiest dictatorships in Latin America. More than 3,000 Chileans were killed or “desaparecido” (disappeared, as the victims were referred to), 20,000 were imprisoned and in many cases tortured and more than 200,000 went into exile, which means that 2 percent of a population of barely 11 million at the time were directly affected by the Pinochet government's brutality.

The Breakdown And The Coup

The 1973 coup was a response to dissatisfaction with the government of Salvador Allende, known as the first Marxist to become president of a Latin American country through open elections. Allende, who was elected in 1970, ruled Chile for three years and introduced socialist-oriented changes including the nationalization of copper mines and agricultural production (still the largest industries in Chile), and social policies intended to improve the welfare of Chile’s poorest citizens, such as scholarships for indigenous children and subsidized housing.

Allende’s measures were opposed by a large sector of the government, including some parties that had supported his election, and in particular, the center-left Christian Democratic Party. Increasing opposition culminated in a declaration of a “constitutional breakdown” by the Parliament and political forces calling for his overthrow by force. On Sept. 11, 1973, the military moved to oust Allende in a coup d’etat. As the Chilean Air Force bombed the presidential palace, La Moneda, Allende vowed not to resign. It nonetheless proved to be his farewell speech: He died that night, of causes still unknown. Although there is no proof, historians have deemed his death a suicide, believing that Allende would have preferred death to imprisonment or forced exile. The army then proclaimed a state of emergency and its leaders installed themselves in power as a military government junta comprised of the heads of the army, navy, air force and police. Because Pinochet was commander-in-chief -- a post he had held since August of that year -- he was made the titular head, and soon after, president of Chile.

The coup was quickly recognized as legitimate by several countries, including the U.S., which had not approved of Allende’s socialist measures. President Richard Nixon’s administration backed all operations against Allende and helped plan the coup, though it was organized and executed from within Chile.

“The U.S. was immersed in the Cold War, and feared a communist expansion throughout South America,” observed Heidi Tinsman, associate professor of history at the University of California at Irvine, who has been studying Chilean history for more than two decades. “Any socialist move was associated with Soviet implications -- though the Soviet Union had very, very little to do with Allende, and the U.S. was never comfortable with Allende’s regime.”

The new regime undid all of Allende's socialist measures. Pinochet took a neo-liberalist approach to the economy with the advice of the so-called “Chicago boys” -- a group of Chilean economists educated in U.S. schools that introduced the principles of the free market into the country. The reform included privatization of all sectors, including public transportation, education and health care, suppression of tariffs, opening Chile to foreign investment and trade, and restricting labor unions. “From a socialist economy, Chile turned into one of the most privatized economies in the world -- and the only one in Latin America,” Tinsman said.

Pinochet prohibited most political parties (though certain right-wing associations were permitted so long as they did not hold meetings or campaign) and boldly prosecuted his opponents and their families, including politicians, diplomats, intellectuals and artists. The Rettig Report, a 1991 study by a Chilean commission designated by then-President Patricio Aylwin to determine human rights violations in the Pinochet years, determined that 2,279 people “disappeared,” while 31,974 were arrested and tortured. Some 200,000 left their country voluntarily to escape the reign of terror while 1,312 were forced into exile. In 2004, then-President Ricardo Lagos requested a second report to build upon the information unveiled by Rettig. Three versions were published over the course of seven years, and the findings added an extra 9,800 victims, including those who were killed, tortured or exiled, and 3,065 who were “disappeared.” The story of the latter was the subject of the controversial 1982 American movie "Missing," starring Jack Lemmon, about an American journalist who disappeared in the bloody aftermath of the 1973 coup (the film was banned in Chile during Pinochet's dictatorship, though neither the country or the dictator are named).

The Reign Of Terror

At the very core of Pinochet’s regime was a deep fear of opposition, and through his military he tried to eliminate any sign of resistance. Over the course of 15 years, several national landmarks, including the soccer stadium, were used as torture centers -- some with the capability of holding up to 3,000 people. There was the infamous Caravan of Death, a military death squad that executed 75 prisoners and buried them in unmarked graves in the desert.

Even high school students, including Carmen Garfias, were targeted. “My parents were conservative, but they knew how I felt." Not one to keep quiet, Garfias spoke openly about her anti-Pinochet convictions, and in her senior year, when she was named student body president, she attracted the attention of the Chilean secret police.

Garfias recalled her first encounter with the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional, or DINA, as the secret police force was called. She and a friend from school had been active in protesting the election of a homecoming queen, a position they claimed had been bought by one of their classmate’s fathers. The girls were called into the principal’s office, where several agents received them and reprimanded them for making too much noise.

“They just did not like us showing initiative and leadership, calling the media, bringing attention to an injustice,” Garfias explained. “And it was just a school election! That is how far and deep they were watching people.”

The DINA did not back down after that. A few months prior to her graduation, Garfias noticed that she was being followed. The police were even present at her commencement ceremony, while she gave her class president speech. “I knew they were there, sitting in the audience, listening to every word. I said that at the very least, they should have brought me a present,” she joked.

But soon after, Garfias became more reticent. People she knew were sent into exile and classmates were arrested; she realized she could be next. "My parents were very pro-Pinochet, until my mother's sister got arrested," she said. "My aunt was held up for months, completely isolated. We don't know if they tortured her. She never spoke about it, not a word."

"My mom was never quite the same after that," she added.

Her husband, Roberto Astudillo, spoke about a childhood friend who was taken by the Caravan of Death. "They buried him alive... He was only 17," he said, and had to leave the room for a minute, overcome with emotion from memories.

Because of her concern, Garfias left her hometown of Antofagasta for the capital, Santiago, 700 miles to the south, to attend university. “I wanted to be more anonymous, I needed to be in a bigger city,” she explained. She recalled how difficult it was not to know who could be trusted, even among her fellow students. “Anybody could be a spy; anybody could have links to the government,” she said. “It was better to stay quiet. You just could not know.” When she met Astudillo in university, she did not talk politics for several months after they got together. They married in 1984.

Garfias lived out the rest of the dictatorship in Chile, and the final years were intense, she said. “People were more united in their opposition to the regime, and we started making our voices heard. We knew the end was near,” she remembered.

After the coup, many Chileans had fled to neighboring countries such as Peru and Venezuela, or as far as Australia and Europe. Among them was Carlos Arredondo, a Santiago native who left in early 1974, a few months after the coup. As a manufacturing worker with basic education, Arredondo expected conditions would become unbearable under the new regime, and decided to escape to Peru, where he had family friends. “My initial plan was to stay in Peru for a few years, until the situation was more stable, and then come back. I never intended to stay abroad for this long,” he said from Edinburgh, where he has lived for almost three decades.

After his Peruvian visa ran out, Arredondo was given refugee status by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. He, along with other Chilean refugees, asked for shelter in several countries, and though he rejected by Canada, the United Kingdom accepted him. “I did not really choose to move to Scotland. Scotland chose me,” he recalled. He flew into London in late 1974, then traveled by coach to Glasgow with 40 other Chileans. They did not speak a word of English nor know anything about life in the U.K., “But we helped each other. We were a community. We lived through it together,” he said.

A musician, he turned to his guitar as a way of communication. “I wrote songs about our home country, I played whenever I had the chance. Music is universal,” he said. He eventually left Glasgow for Edinburgh, “for love,” where he got married and had a daughter and a son. He also became a spokesperson for the refugees, and a well-known activist for the cause of his country. He recalled the moment when he heard the news that six of his childhood friends had been disappeared in the 1980s.

Overthrown By Popular Vote: The Plebiscite

Pinochet’s dictatorship stands as the only authoritarian regime to date that was not overthrown by the opposition, or a social upheaval, or the death of the leader. In fact, Chile’s military regime was brought down by the very thing it tried so hard to suppress: Citizens' choice.

In 1980, Pinochet tried to legitimize his government through a Constitution accepted by plebiscite. The document, which included among its articles the banning of all political parties and the acceptance of Pinochet as President, called for another referendum to be held eight years later, at which point Chileans would decide if they should grant the government another eight-year extension. Despite the measure's democratic guise, its primary aim was to create an impression that PInochet was a magnanimous, fair leader, Tinsman said. By the time the second plebiscite’s date rolled around, opposition to the regime was rising, both within Chile and internationally. Social protests grew larger and more frequent, and eventually the Catholic church -- a longstanding opponent of the regime -- called for elections and for Pinochet's resignation.

Faced with such increasing pressures, Pinochet's government legalized political parties and campaigns in 1987 and set a date for the plebiscite of Oct. 5, 1988. During the referendum, a "yes" vote meant that Pinochet would remain president, though general elections would follow. If the majority of the votes were "no," Pinochet would step down after a year and joint elections for parliament and government would be held.

The opposition parties formed the Concertación de Partidos por el NO (Coalition of Parties for NO),which hired an advertising agency to design a cheerful, colorful campaign with the slogan “Chile, la alegría ya viene” ("Chile, joy is coming"). Eugenio García, the creative director of the campaign, said the goal was to inspire people with the idea that the best was yet to come. “The problem we faced was fear. People were afraid of the outcome of the plebiscite, whichever it was,” he explained. Garcia, whose own experience was loosely represented in the 2012 Chilean film “No,” recalled, “People feared going back to dark time, and feared repression like in the early days of the regime. The campaign spoke to people with the right words for the time, and inspired citizens to be brave and express their real feelings towards the regime.”

The “no” votes won with a 55.99 percent of the ballots cast.

“The outcome was a surprise to everybody -- including the 'no' supporters,” Tinsman explained.

Chileans were ecstatic, yet circumspect. Garfias remembered how until the very last minute most people assumed “yes” would win. “The news kept on saying that the 'yes' had the majority for most of the count,” she said, recalling her joy when the actual results were announced. “We could not believe it, we seriously could not. Celebrations were not immediate -- it took a few hours for people to take [to] the streets in joy. And even then, we were discreet, careful. We had no idea what would happen to us, if the army would take the streets again.”

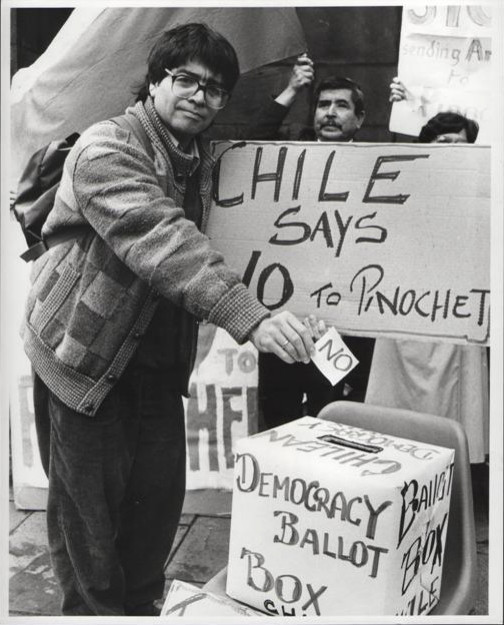

Chileans in exile followed the plebiscite closely from abroad. In Scotland, Carlos Arredondo held his own symbolic referendum, casting his “no” vote in a makeshift poll. His photograph appeared in the front page of local newspaper The Scotsman, alongside a picture of Pinochet casting his “yes” vote. “It was my duty as a Chilean,” Arrendondo told IBTimes. “Even if it did not count, I wanted to give my opinion, too.”

Despite the joy of Pinochet’s opponents, the very narrow victory illustrated deep division within Chilean society. “Whether those who voted for 'yes' did it out of conviction or fear, we will never know, but the fact is almost half of the population wanted Pinochet to still rule the country,” Tinsman said. “It just demonstrated just how divided citizens still were.”

Pinochet accepted the results and stepped down as President in March 1989, leaving the path open for a democratic Chile. He did not disappear from political life, however; he continued to hold the title of commander-in-chief of the Chilean army until 1998, after which he was designated senator-for-life, which granted him judicial immunity in his home country.

Democratic Chile: Then, Today And Tomorrow

The much-awaited democratic government in Chile restored public political participation and social freedoms but did not bring all the expected reforms. Notably, the privatization of government services remained. "Still today, Chile is one of the most privatized countries in the world," Tinsman said. "Even public transportation and public housing are private.”

An as Arredondo pointed out, economic inequality is pronounced in Chile. "The country has grown, yes, but not for everybody,” he said. In fact, the World Bank’s GINI Index -- the most commonly used measure of economic inequality, ranked Chile worse that developing countries such as Angola and Cambodia.

Democracy also failed to provide redemption and justice for the families affected by the regime's brutality. Immune within Chile because of his political designation, Pinochet was never brought to trial for human right violations in his home country. It was not until 1998, when he was arrested during a trip to London under orders of Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón that the question of taking the old dictator to court was even considered. “After everything Chile went through, we could not even ask for justice,” Garfias lamented. “Pinochet had to travel abroad for it to even be considered.”

Garzón opened a case against Pinochet for human right violations against several Spanish citizens during his time in power. The general, then 83 years old, claimed dementia, and Chile asked for him to be returned home. He stayed under house arrest while the charges were processed, and passed away in 2006 before beingcalled into trial.

In Tinsman's view, the fact that Pinochet never appeared before a judge should not be interpreted as meaning he was never brought to justice. “Pinochet died completely de-legitimized,” she said. “He had been recognized as a dictator and a murderer. He never went to prison, but that does not mean that he left with the estimation of the people.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.