China Is Catching Up To The US On Artificial Intelligence Research

Researchers, companies and countries around the world are racing to explore – and exploit – the possibilities of artificial intelligence technology. China is working on an extremely aggressive multi-billion-dollar plan for government investment into AI research and applications. The U.S. government has been slower to act.

The Obama administration issued a report on AI near the end of its term. Since then, little has happened – until a Feb. 11 executive order from President Donald Trump encouraging the country to do more with AI.

The executive order has several parts, including directing federal agencies to invest in AI and train workers “in AI-relevant skills,” making federal data and computing resources available to AI researchers and telling the National Institute of Standards and Technology to create standards for AI systems that are reliable and work well together. These are all good ideas, but they lack funding and bureaucratic structure. So after researching how large organizations use AI for the past five years, in my view the executive order alone is not likely to transform the American approach to AI.

Government spending

China is doing far more than talking about AI. In 2017, the country’s national government announced it wanted to make the country and its industries world leaders in AI technologies by 2030. The government’s latest venture capital fund is expected to invest more than US$30 billion in AI and related technologies within state-owned firms, and that fund joins even larger state-funded VC funds.

One Chinese state alone has said it will devote $5 billion to developing AI technologies and businesses. The city of Beijing has committed $2 billion to developing an AI-focused industrial park. A major port, Tianjin, plans to invest $16 billion in its local AI industry.

These government programs will support ambitious major projects, startups and academic research in AI. The national effort also includes using AI in China’s defense and intelligence industries; the country’s leaders are not reluctant to use AI for social and political control. For example, both AI-driven facial recognition, even to catch jaywalkers, and “social credit” – an AI-driven credit score that factors in social behaviors – are already in use.

U.S. investment plans, mostly in the defense industry, are dwarfed by the Chinese effort. DARPA, the Defense Department’s research arm, has sponsored AI research and competitions for many years, and has a $2 billion fund called “AI Next” to help develop the next wave of AI technologies in universities and companies. It’s not yet clear how much real progress its efforts have made.

Private sector contributions

The U.S. has a strong private sector effort in this technology. There are, for instance, many more AI firms in the U.S. than in China.

American investment appears strong, too. In 2015, for example, the combined research and development spending at the U.S.-headquartered companies Google, Apple, Facebook, IBM, Microsoft and Amazon was $54 billion. Much of that spending went toward AI research, but some of the work actually happened in China and elsewhere outside the U.S. That work has been used to personalize ads, improve search results, recognize and label faces and generally make products smarter.

In China, the private sector is much more closely tied to government plans than in the U.S. The Chinese government has asked four large AI-oriented firms in China – Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba and iFlytek – to develop AI hardware and software systems to handle autonomous driving and language processing, so other companies could build on those skills.

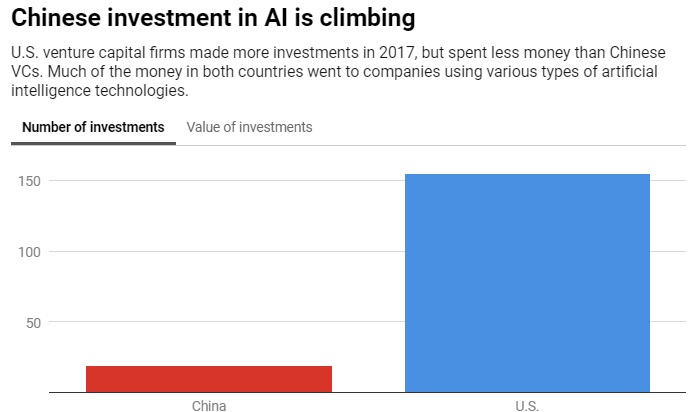

China may have also surpassed the American historic advantage in venture capital investments. In 2018, U.S. AI startups received $9.3 billion in venture funding – a record amount, but the number of deals was down from 2017. However, one report from China suggests that in the first half of 2018, Chinese venture investments – many of which involved AI – were higher than in the U.S. Data from 2017 suggest that Chinese AI firms received more venture funding than U.S. companies, although the American funding went to many more firms.

Beyond investment money

There are other factors than investment that determine a country’s long-term competitiveness on AI. Talent is an important one. The U.S. had an historical edge in this regard, with strong technical universities, many technology sector employers and relatively open immigration policies.

A recent analysis of LinkedIn data suggests that the U.S. has far more AI engineers than China does. But China is closing the gap rapidly, with a variety of education and training programs beginning as early as elementary school. The Trump administration’s restrictions on immigration are encouraging some of the world’s best AI researchers to stay home, rather than come to the U.S.

Another element in long-term AI success is how particular regions build mutually reinforcing communities of companies, university ecosystems and government agencies. Silicon Valley is the world leader in this regard, and China doesn’t have anything to match it yet. Both the U.S. and China could learn from efforts in Canada, such as the work by the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms, which has offered companies access to facilities, venture capital and university research partnerships to accelerate AI development in that city.

A final key element in AI progress is data: The more data a country’s companies have, the better able they are to develop capable AI systems. Chinese online firms have massive amounts of consumer data on which to train machine learning algorithms. Because of its very large number of inhabitants, the population’s heavy use of digital services and its lax regulatory environment, China clearly beats the U.S. on data.

I still think the U.S. has the edge over China in AI capabilities at the moment. However, as much as I would like the U.S. to win this race over the long run, if I were a betting man I would bet on China. As I describe in my new book “The AI Advantage,” China is executing its strategy for AI, and the U.S. is still wrestling to create one. China is also reaping the benefits of having a determined government, an inexhaustible pot of money, a growing cadre of smart researchers and a large, digital-hungry population.

Perhaps if the leadership of the U.S. government devoted as much attention and investment to AI as it does to its other strong priorities, the U.S. could maintain its lead in the field. That seems unlikely over the next couple of years, however.

Thomas H. Davenport is a professor of Information Technology and Management, Babson College.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the article here.