China To Send UN Troops To South Sudan, Denies Deployment Related To Oil Investment

China will send 700 troops to South Sudan as part of a U.N. peacekeeping mission to help civilians after nine months of violent conflict that has threatened Chinese oil investments.

Beijing has had interests in the region for decades, and today gets 5 percent of its oil from South Sudan. Though China’s foreign investment policy has, at least publicly, involved non-interference with local politics, the situation in Sudan has been especially complicated over the year. And now it’s starting to affect its bottom line, drawing the world's second-biggest economy into the volatile region.

“Sudan is a place where global aspirations and practical economic and commercial considerations intersect,” Jennifer Cooke, director of the Africa program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told International Business Times.

While the West tends to contribute to sub-Saharan Africa through aid or loans, China has always focused on business. While the tactic has drawn criticism from many parties who accuse Chinese companies of taking advantage of resources without adding to the local economy or employing local workers, it’s helped them do business in many regions where other companies refuse to go.

“One of China’s big selling points to African leaders as it expanded in Africa is this policy of non-interference, that it would stay out of internal affairs,” Cooke said, adding that being under the neutral umbrella of the U.N. will help keep this at least partially true.

But in Sudan, which is responsible for roughly 5 percent of Chinese oil imports, it hasn’t always been simple.

While western firms such as Chevron had a presence in the country in the 1960s and 1970s, they pulled out during another civil war in the 1980s the made the situation in the south unstable. The state-run China National Petroleum Corp., joined the country’s oil consortium in 1996 and spent millions on infrastructure to ramp up production.

Despite an overt policy of non-interference in political affairs, in the early 2000s it was Chinese weapons and oil investment money that financed government-sponsored Arab militias that pushed local tribes off their land in the highly disputed Darfur region, intensifying a decades-old civil war.

After the South Sudanese Independence referendum on 2011, China was caught between the two countries. After heavily supporting Khartoum for the previous decade, it now had to make peace with both sides, and has since become a negotiating force.

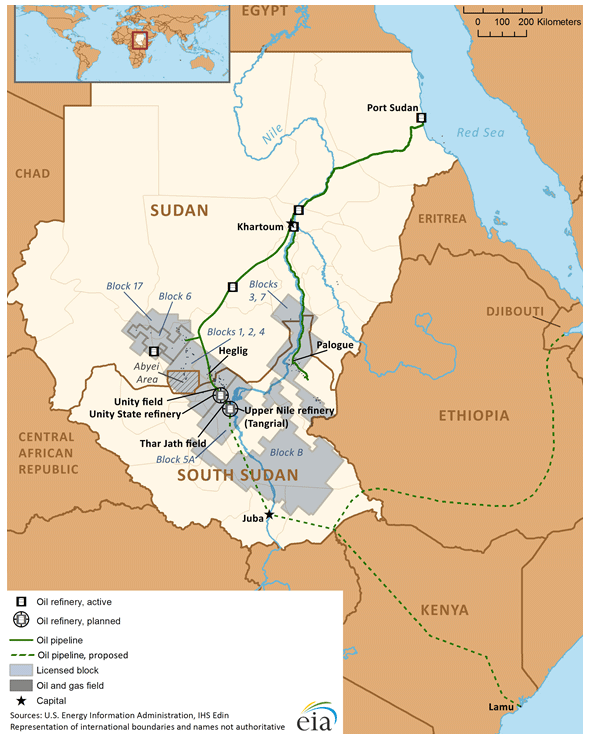

Between the two countries, the vast majority of oil comes from South Sudan but is exported through the nation's state-run Greater Nile Oil Pipeline (GNPOC) that runs from Unity Oil Field to a Red Sea port, via Khartoum. This 990-mile line was built in 1999 by the GNPOC, which still operates it today. China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) is the consortium’s largest stakeholder, with a 40 percent stake. Malaysia’s Petronas and India’s state-run Oil & Natural Gas Corp. Ltd., are also partial owners.

“The irony of all this conflict is that Sudan and South Sudan need each other and China, therefore, needs them both as well,” Cooke said.

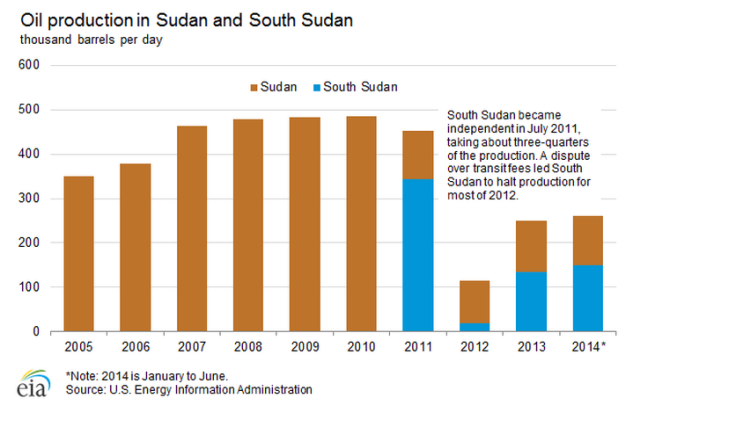

Sudan and South Sudan’s oil production averaged 260,000 barrels per day in the first half of 2014, down from nearly 490,000 in 2010, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

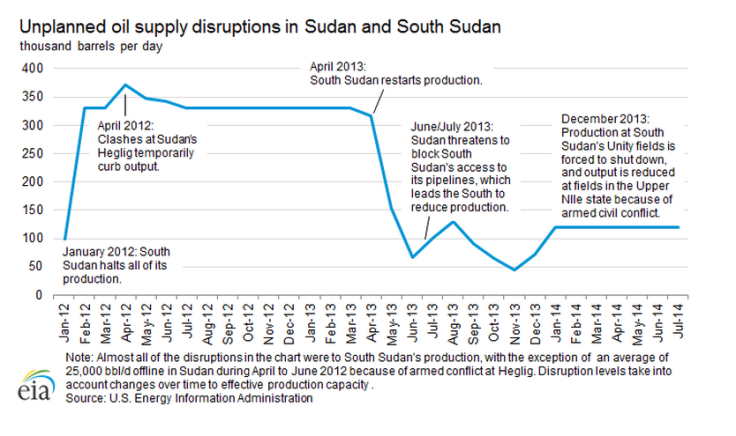

Even after South Sudan became its own country, the situation was far from stable.

“Disagreements over oil revenue sharing and armed conflict have curtailed oil production from both countries over the past few years,” an EIA report says.

It halted oil production in February 2012 after a dispute over transportation fees. Before the shutdown, oil accounted for 98 percent of South Sudan’s revenue. Even after the oil started flowing 15 months later, tensions remained high, erupting into a civil war that began in December 2013 and has raged ever since.

By May of this year, the United Nations mandated that its Mission in South Sudan should stay longer than initially intended to address growing violence and the displacement of millions due to the conflict. Soon after, China secured a deal with the organization to send in peacekeeping forces. The U.N. resolution calls for Chinese troops to be deployed to “protect civilians and deter violence against them,” and “create the conditions necessary for the delivery of human aid.”

Though this is actually the second time China has sent U.N. troops to Africa, it’s certainly the largest group, according to Yun Sun, a visiting fellow at the the Brookings Institute's Africa Growth Initiative, which focuses on China-Africa relations.

“The key issue is not China sending troops to UNPKO [United National Peacekeeping Operations], which China has done before, the key issue is what kind of peacekeeping force that China sends and where,” Sun told IBTimes.

She said that despite the fact the U.N. and the Chinese government have denied the mission is motivated by oil, “the correlation leads to speculations on causality.”

“They basically said that they wanted to be where the oil is,” Foreign Policy quoted one official saying during the negotiations. But the publication also noted that eventually China agreed to send people into regions where it didn’t have oil interests.

Joe Contreras, acting spokesman for the U.N. Mission in South Sudan, emphasized earlier this month that the troops first priority will be protecting civilians.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.