China Shadow Banking, Fed Tapering: Credit Crunch Forced PBOC To Give In; Will The Fed Hold Firm?

In response to the global financial crisis, the world’s two largest economies loosened up their fiscal and monetary policies to keep their economies afloat. Five years and trillions of dollars later, China and the U.S. are arriving at a crossroad again. Only this time, instead of pumping more money into the system, both countries seem (somewhat) determined to mop up excessive liquidity.

The most recent market upheaval was sparked by the two central banks’ attempt to "prick" asset bubbles.

The People’s Bank of China, initially standing firm and refusing to bow to pressure to flood the interbank market with more cash, has taken a step back. After all, trading short-term pain for long-term growth isn’t as easy as it sounds. On the other side of the Pacific Ocean, U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke is playing a potentially dangerous game of chicken with global financial markets. His latest comments on Fed tapering led to a bloodbath in financial markets, with stocks plunging, a gold selloff intensifying and bond yields shooting up. Now, all eyes are on Bernanke. Will he blink?

China’s Credit Crunch And Shadow Banking

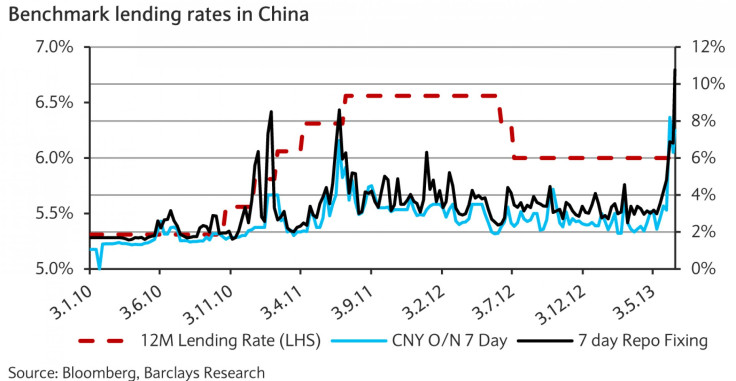

Money market rates in China soared last week after authorities allowed cash market conditions to tighten. Shibor, the Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate, surged to a record high of 13.8 percent and the overnight repo rate hit 25 percent last Thursday.

On Monday, the People’s Bank of China publicly issued its first statement regarding the rate spike, essentially telling the financial sector not to expect the central bank to always be ready to bail them out with more liquidity. The central bank had actually circulated this statement to banks on June 17 but only made it public on Monday.

“In our view, the PBOC is signaling to the market that it will not endlessly tolerate some banks’ reckless liquidity management and overdependence on the interbank market for facilitating their asset expansion off-balance sheets,” wrote S&P analysts in a note published on Monday.

The PBOC’s inaction sent Chinese shares into a tailspin, falling to their lowest since early 2009. The PBOC eventually softened its position as market conditions continued to worsen. "In order to maintain the stable operation of the money market, recently the central bank has provided liquidity to some qualified financial institutions," China’s central bank said in a statement on its website on Tuesday.

While the spiking interbank lending rates may be only a temporary flare-up, they do reveal the depth of China's banking troubles. Over the past year, the economic slowdown has caused some of the country's massive shadow lending to unravel. The proliferation of China’s opaque, loosely regulated (or unregulated) shadow-banking system has been raising fears of possible financial instability.

Shadow banking can take many forms, including loan sharks, investment companies known as trusts, and off-balance-sheet lending by regular banks. The most important of the latter are “wealth-management products,” which are considered potentially dangerous.

Overall, credit in China has jumped from $9 trillion to $23 trillion since the Lehman crisis, Yiping Huang and Jian Chang, China economists at Barclays, said in a report to clients.

"They have replicated the entire U.S. commercial banking system in five years," Charlene Chu, Fitch ratings agency's senior director in Beijing, told the (U.K.) Telegraph.

Total credit in the Chinese economy has jumped by 75 percentage points to 200 percent of gross domestic product -- it was only 40 percent before the U.S. subprime bubble burst. Mainland banks are adding assets at the rate of an entire U.S. banking system every five years, according to Fitch.

Shadow banking in China is dominated by lending to higher-risk borrowers, such as local governments and property developers. Therefore, the real concern in China isn't the volume of shadow credit, but its quality, and the banking system’s capacity to absorb potential losses.

Concerns are rising after rumors surfaced in the Chinese media last week that the central bank provided emergency assistance worth “less than” 400 billion yuan (about $65 billion) to two of the Big Four state-owned commercial banks: Bank of China (HKG:3988) and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (HKG:1398). If accurate, these rumors show that the cash shortage isn't limited to medium-sized lenders such as China Everbright Bank Co., Ltd (SHA: 601818), whose Shanghai branch defaulted on a 6 billion-yuan loan repayment to Industrial Bank Co., Ltd. (SHA:601166) on June 6.

The Big Four form the backbone of China's financial system and a bailout would suggest that the entire system is severely strained.

Prof. Bernanke Meets Mr. Market

Since the financial crisis, the Fed has often found itself forced to respond to markets, rather than lead them. But Bernanke appears to have been a tough talker lately by signaling the markets since May 22 that the tapering of quantitative easing could start “in the next few meetings.” The Fed has launched three rounds of quantitative easing, or QE, since the financial crisis hit in 2008. As a result, the Fed’s balance sheet has swelled to some $3.3 trillion.

During the bleakest crisis days, the Fed often had little choice but to give in. Now, the market is once again pushing and testing the Fed over its latest change in policy.

"Markets tend to test things," Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher told the Financial Times. "We haven't forgotten what happened to the Bank of England [on Black Wednesday.] I don't think anyone can break the Fed … But I do believe that big money does organize itself somewhat like feral hogs. If they detect a weakness or a bad scent, they go after it."

Stocks plunged and bond yields spiked last week when the Fed announced plans to reduce its bond purchases this year and end the program when the unemployment rate hits about 7 percent, which is expected to occur in mid-2014.

Obviously, the Fed can't let things get out of hand. But at the same time, it can't paint itself into a corner. This time, the Fed has to hold firm and deliver a clear message to the financial markets: Every party must come to an end.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.