China's Economic Hard Landing: Think Twice Before Gloating Over China’s Slowdown

For those who were anxious over the voraciousness of the modern Chinese economy -- the country’s breakneck development since the 1980s, its mounting influence over global trade, its expanding ownership of other nations’ debt -- China's current slowdown may seem welcome, in a perverse way. For years, the largely unstated admonition has been: Seriously, China, slow down.

Yet the reality is that a major Chinese economic slowdown could spark a crisis of monumental proportions, damaging every economy in the world, and the Chinese government has yet to show how it will prevent that from happening. After overseeing what may well have been the fastest growing economy in human history, China is trying to come to terms with how to manage its inevitable slip -- to minimize the damage while putting in place structural reforms involving improvements in tax and exchange rates and minimizing cozy government relationships with companies to enable long-term recovery and sustainability.

No one knows if they will succeed, and the stakes are high -- for everyone.

“The slowdown in economic growth that Chinese policymakers seem to be accepting or maybe even attempting to engineer is not going to be smooth … it’s going to be a bumpy ride,” observed Robert King, senior economist at the Jerome Levy Forecasting Center in Mt. Kisco, N.Y. “It’s a very dangerous move.”

Yet analysts say the government has no choice but to accept the reality of a long-term downturn. All signs indicate that time is running out on China’s current economic model, which has relied on throwing mountains of cash into building factories and roads and employing millions of poor people in the manufacture of iPads and blue jeans. With most of the low-hanging fruit picked, China’s leadership faces the potential for far worse: A credit collapse, wasted resources, debasement of the country’s financial sector and faltering global partnerships.

For the first time in recent history, China’s leadership has shown a willingness to tolerate short-term pain in the interest of setting the economy on a more sustainable path, but so far it has been unable to deliver the needed structural reforms. Earlier this month, the International Monetary Fund revised down its growth prospects for the entire world, and China stood out as one where they don’t see a bounce-back coming.

“In their charts, the global economy, the industrialized countries, and even the emerging markets as a whole, they slow down in 2012, they are kind of flat in 2013, and then they bounce in 2014,” King said. “But in China, this slowdown just continues. Once you start to have expectations that are centered around a lower level of growth, then there’s lots of ability to slip significantly below that.”

All of which matters far beyond China’s borders. If the country’s excessively liberal borrowing policies, slowing consumer demand, and decreasing employment cause growth to slow to a trickle, as appears to be happening, its expansion of overseas partnerships will be jeopardized, as will the economies of those partners.

“China, for a long time now, has been an important driver of basically every country’s economy,” said Raphael Bostic, a University of Southern California public policy professor and former HUD assistant secretary. “Any slowdown is going to ripple through and really have an adverse impact on the world’s economic performance. It’ll hit in some places worse than others.”

Current Thinking on Chinese Growth and GDP

China’s phenomenal GDP growth briefly touched 15 percent on the eve of the 2008 global financial crisis, but during the last quarter its economy -- the second largest in the world, after the United States -- grew at half that rate. (Generally speaking, GDP is calculated by adding consumption expenditures, investment spending, government expenditures and net exports.)

The nation’s export engine is now sputtering (down 3.1 percent year-over-year in June, marking the first decline since January 2012) and its factory activity has dropped to the lowest levels since the financial crisis (a preliminary reading on the HSBC China Flash PMI for July is now at 47.7; a reading below 50 indicates contraction.) What’s more, for the first time in years, there is a realistic prospect that the Chinese economy will miss the government’s annual target for growth.

Indeed, China watchers worry about the potential for a hard landing, in which the economy slows to the low single digits. French Bank Societe Generale foresees China's growth rate at just 6 percent in five years’ time and as low as 4 percent to 5 percent by the end of this decade; London-based Barclays forecasts growth falling to 3 percent or below within the next three years. “Not only will China’s real GDP growth drop as China shifts toward a different growth engine, but it will drop even more as China is forced to recognize the hidden losses buried in its debt levels,” predicted Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University and a well-known China bear, in a recent newsletter.

Reformist Premier Li Keqiang said at a recent meeting with economists that the bottom line for growth this year is pegged at 7 percent, and “this bottom line must not be crossed.” Beijing has set a full-year growth target of 7.5 percent for 2013, but, as Jerome Levy’s King noted, “The bottom is well below 7 percent.”

“Their options are getting fewer and fewer,” King said. “There’s really not much room for investment. Attempts to spur the economy with credit growth are leading to financial problems and you’ve got a shrinking pie of weak global trade flow. So the ability to just make that target [7.5 percent] happen, except through fudging the numbers, is very low.”

How China Reached Its Limits

Following the financial crisis in 2008, external demand for Chinese products declined sharply and net exports ceased to be a driving force for the Chinese economy. The government responded by engineering a monetary stimulus, which translated into a lending boom, which translated into an investment boom. So, as Chinese net exports declined from 8 percent of GDP to 2 percent, investment in China rose from 43 percent to almost 50 percent -- the highest in the world and far higher than the figure in Japan or Korea during their catch-up spurts.

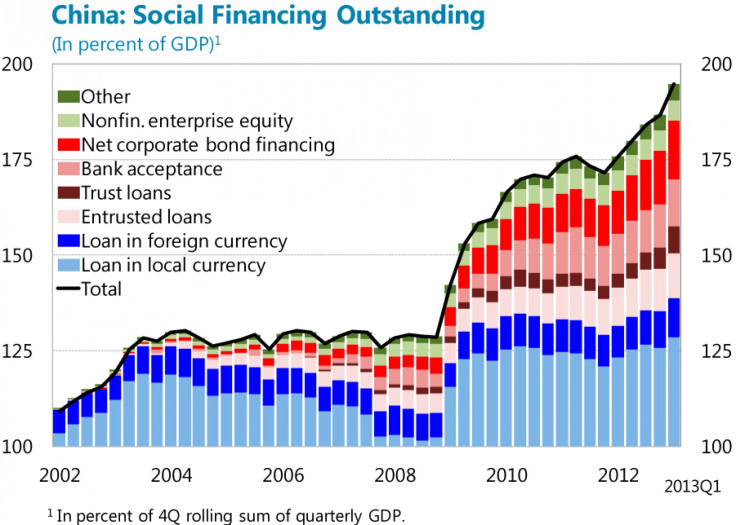

Today, China is in the midst of a classic credit bubble. Before 2008, credit was expanding at roughly the same rate as the economy, which means the credit-to-GDP ratio was flat. Since 2008, total credit in the Chinese economy has jumped by 75 percentage points to 200 percent of GDP; by comparison, the rate was only 40 percent before the U.S. subprime bubble burst. Mainland banks are adding assets at the rate of an entire U.S. banking system every five years, according to Fitch.

“Economic history suggests that rapid increases in credit often end in crisis,” said Mark Williams, chief Asia economist at Capital Economics. Those similar surges of debt have toppled other economies into financial crises, including South Korea, Japan and the U.K.

Much of this has come in the poorly regulated “shadow banking” sector, where the annual rate of credit expansion exceeds 50 percent. Shadow banking in China is dominated by lending to higher-risk borrowers, such as local governments and property developers. Local government debt has escalated in recent years, to an estimated $2 trillion, or 25 percent of GDP. George Soros recently warned that shadow banking could be as risky as the toxic subprime-mortgage securities that tanked Wall Street.

“The biggest mistake would be if China’s government targeted excessive fast growth and fed a worsening asset bubble,” said Bill Adams, senior international economist at PNC Financial. “They are not doing that and that’s the right choice.”

With stability in mind, the Chinese authorities now seek to reduce reliance on credit-fuelled investment, which leaves consumption as the main engine of growth. Yet in the three months ending in June, investment remained the single largest driver of economic expansion, its contribution to growth twice as large as consumption.

“As you fly into a city, you see cranes everywhere,” Raphael Bostic of USC said, describing his observations during a recent trip to China. “There are a lot of large buildings and they are not all fully occupied, and yet, building is continuing pretty aggressively.”

“At some point, investment has to be linked to the level of actual production. You can’t invest just to invest,” Bostic said.

Observers who are optimistic about the Chinese economy -- the “panda huggers” -- believe the economy will be stable, at least, if the government institutes painful structural reforms. Among them, extending value-added tax to services to slow down that sector, liberalizing interest and exchange rates, and restructuring state-owned enterprises. Their counterparts, the “dragon slayers” (as the pessimists are known) warn that the risks of rebalancing the Chinese economy are high. Chinese investment, they say, could drop before consumption picks up, turning a slowdown into a hard landing.

It’s a matter of how low the GDP numbers fall, and how fast, and how long they stay there before rebounding. For now, the government is ordering some industries to cut excess production capacity and rolling out a host of minor stimulus measures -- the latter a familiar response that in some cases has led to overbuilding. The Chinese leaders want to slow the economy down, but at a pace that they are comfortable with. So, while targeting overcapacity, they are unveiling mini-stimulus measures (tax cuts for small businesses, accelerated railway construction and investment, etc.) as opposed to massive stimulus measures such as were undertaken in 2008.

Whatever the government does, the slowdown will continue -- it’s just a question of duration and pace.

When China Sneezes, Everyone Else Gets Sick

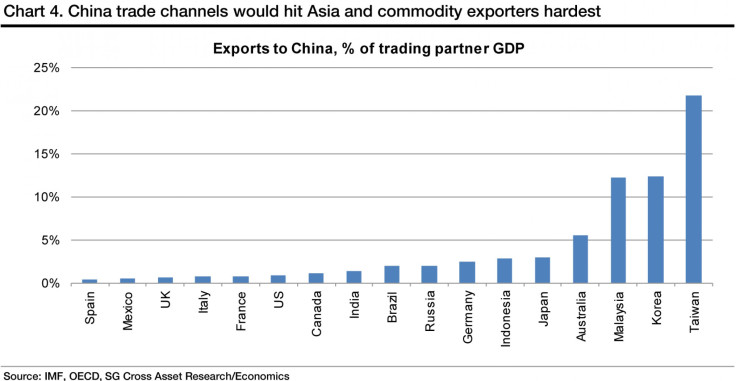

The impact of a sharp further deceleration in Chinese domestic demand would be pervasive on global GDP, predicts Julian Callow, chief international economist at Barclays PLC. During the past five years, China accounted for 43 percent of worldwide growth. A serious decline in China's growth rate would reverberate around the world as the world’s biggest consumer of raw materials loses what seemed to be an insatiable appetite. From Australian miners to South Korean consumer electronics manufacturers, the major beneficiaries of China’s astronomical growth are now the most vulnerable.

China’s investment boom has been the key driver of stronger demand for copper, iron ore and steel over the past decade. As a result, the first set of economies affected by a dramatic slowdown would be big commodity producers that sell to China or rely on its demand indirectly. In the past 15 years, China has built 90 million new homes -- enough to house the populations of the U.K., France and Germany combined. A quarter of global steel demand is for Chinese property and Chinese infrastructure -- its share demand rose from 16 percent in 2000 to 44 percent 2012 (in nickel, its share jumped from 6 percent to 45 percent). This consumption drove prices of almost all commodities to record highs. But as China slows down, copper, iron ore and coal have all fallen 30 percent to 50 percent from their 2011 peaks.

Australia, a commodity-rich country, dispatches more than a quarter of its exports to China, its biggest trading partner, and iron ore accounts for 60 percent of those goods. As Prime Minister Kevin Rudd recently said, his country now faces the end of a decade-long resources boom in which China represents 10 percent of GDP. Australia’s resources industry accounts for almost 10 percent of the nation’s job market -- about double the level a decade ago -- and close to 20 percent of national output, with coal and iron ore among the country’s largest exports. “The truth is, in 2013, the China resources boom is over,” Rudd said. “We find ourselves at a crossover point for our national economy. If we make the wrong decisions now, we will be living with those decisions for the decade ahead.”

China is also South Africa’s largest trading partner and a key buyer of commodities such as platinum-group metals, gold, coal and iron ore, which together account for 41 percent of South Africa’s yearly exports. Meanwhile, China’s economic slowdown will most likely have a substantial effect on its Asian neighbors. Total trade between China and the ASEAN economies has grown more than 30-fold in the last 15 years, making China ASEAN’s largest trading partner. Countries such as Indonesia, which exports natural resources including coal, tin, rubber, cocoa and palm oil to China, and Thailand, which exports rubber and computer parts to China, are expected to take a hit. Another vulnerable economy is South Korea, whose exports have been the main driver of growth for the country. As South Korea’s largest export market, China takes in a quarter of total overseas shipments from the smaller neighbor.

Analysts forecast that a Chinese hard landing would lead to a 30 percent to 40 percent drop in base metals prices and a 30 percent fall in Brent crude oil prices. As prices fall below the cost of production, they should recover over the subsequent 6 to 12 months, but the pace of the recovery would be uncertain. Societe Generale's global head of commodities research Michael Haigh believes gold could initially bounce on a Chinese hard landing, but because Chinese savers are big buyers of gold, the impact could be short lived and the volatility of gold could increase. While lower prices could hurt commodity-producing countries, it could benefit importers -- countries such as the Philippines, the Czech Republic, India and Turkey.

“As China’s demand for commodities such as aluminum, coal and oil, come down, it starts to cause a downward pressure on commodity prices,” said Bhaskar Chakravorti, dean of international business and finance at Tufts University's Fletcher School. “It’s going to benefit countries that are importers of commodities, and to a large extent, have been paying the higher cost of commodities.”

Germany, Europe’s powerhouse, is already experiencing a rapid decline in exports to China -- its fifth largest trading partner in 2012 in terms of exports. Some 67 billion euros ($87 billion) worth of goods, or around 6 percent of Germany’s exports, were shipped to China last year. But German shipments to China fell 7 percent in the first quarter of this year compared to the same year-ago period. According to Deutsche Bank, that loss is equivalent to 0.5 percent of German GDP, which has already affected some German companies.

Bentley, owned by carmaker Volkswagen AG (ETR: VOW), said earlier this month that it delivered only 817 cars to China in May, a 23 percent decrease from last year. Siemens AG (ETR: SIE) now expects slowing growth to continue into the fiscal 2013 year, especially in peripheral Europe and China. German business software maker SAP AG (ETR: SAP) also trimmed its sales outlook for this year, warning that a slowdown in China was prompting companies across Asia to put investments on hold. If German exports to China continue to slow, it would be bad news for the euro zone as a whole, as Germany is the region’s strongest economy.

According to Societe Generale’s calculation, a major slump in Chinese growth would cut 2013 global GDP growth from 2.6 percent to 1.3 percent and trim overall world GDP by 0.3 percentage points. Looking at individual countries, a hard Chinese landing would cut GDP growth by around 4.5 percentage points in Taiwan, 2.5 percentage points in South Korea and Malaysia, 1.2 percentage points in Australia, 0.6 percentage points in Japan, 0.2 percentage points in the euro area and 0.1 percentage points in the U.S.

Unless there is a very hard landing, China’s slowdown is expected to have a marginal effect on the U.S. in part because demand for some of the top exports to China -- airplanes and high-tech computer goods -- has remained relatively strong. And while U.S. exports to China have grown more than six-fold since 2000, shipments to China still only account for around 7 percent of total U.S. exports. “U.S. exports to China are at about $120 billion a year. So if $120 billion is cut by 5 percent, it’s a decline of $6 billion. We are a very large economy; it’s not going to have an enormous effect on us,” said Sonecon’s Robert Shapiro.

Still, if China and other national economies are adversely affected, the U.S. economy will be, as well. It’s just a matter of degrees.

According to Societe Generale’s China Economist Wei Yao, two types of events could trigger a hard landing in China. One is that trade shocks lead to a sharp deterioration in exports and loss of migrant worker job. The other is that there is insufficient public investment from Beijing or intended credit deleveraging gets out of control. Whatever the catalyst, the excess capacity in the manufacturing sector -- estimated at 40 percent in 2011 by the IMF -- would be exacerbated by a sharp growth slowdown, which would dramatically reduce corporate margins, causing profits to plunge and triggering a downward spiral in domestic demand. Bankruptcies and unemployment would occur on a large scale, endangering financial and social stability. And the high leverage of China’s corporate sector and local governments could accelerate the downward spiral.

As the crisis progresses, non-performing loans would undoubtedly rise beyond the capacity of local governments to contain them, as their fiscal resources dwindle. “Even in China’s (semi-) controlled system, banks could choose to freeze lending as a knee-jerk reaction, while the authorities rush to draft a decisive response,” Yao said.

Yao noted that investment, which makes up half of Chinese GDP, will fall more than consumption if China does suffer a hard landing. And investment has significantly higher import content than consumption, most notably through commodities and machine tools, which could have a particularly sharp impact on some smaller commodity producers.

Ultimately, whether the Chinese economy is headed over a cliff is open for debate (especially considering the reliability of the government statistics.) What is clear is that the past 30 years is a tough act to follow. And to return to steady growth, the government will have to move quickly with reforms that fundamentally change the way the Chinese economy has been managed for the past three decades, while having no guarantees that any of it will work.

“When you are talking about restructuring a giant economy like the Chinese economy … I don’t know what more they [Chinese leaders] can do,” said Ravi Ramamurti, director of the Centre for Emerging Markets at Boston’s Northeastern University.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.