As China’s Interbank Liquidity Crisis Worsens, Chinese Censors Ban Media Use Of The Term 'Cash Crunch'

It’s June all over again in China. A cash crunch worsened on Monday in the world’s second-largest economy despite the central bank’s repeated attempts to calm the market by injecting liquidity. Beijing has become so worried that propaganda authorities have told local media to tone down their reporting.

The weighted average of the seven-day repurchase rate, an important gauge of short-term liquidity in the banking system, soared last week and brought back memories of the June liquidity squeeze that spooked investors and rocked global financial markets.

In a sign that banks are still reluctant to lend to each other, the benchmark money-market rate climbed to 8.94 percent on Monday from 8.21 percent Friday, marking its highest level since it hit 9.29 percent June 21.

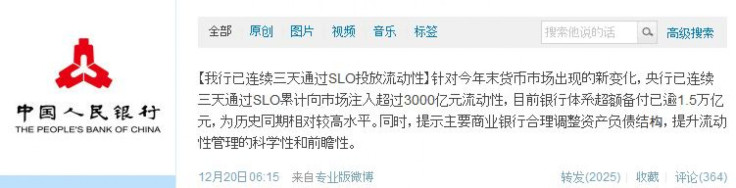

The jump in rates came despite the People’s Bank of China’s announcement on Friday that it had carried out “short-term liquidity operations” to alleviate the problem. China’s central bank pumped more than 300 billion yuan ($49.4 billion) into the financial system to prevent another damaging cash crunch this year. The PBoC also took the unusual step of publicizing the move on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter.

In another attempt to “fix” the problem, Chinese propaganda officials have ordered some media outlets to tone down their coverage of the latest liquidity squeeze, two people with direct knowledge of the matter who asked not to be named told the Financial Times.

Financial reporters are not allowed to “hype” the story of problems in the interbank market, and in some cases, according to the FT, have been forbidden from using the Chinese words for “cash crunch” in their stories.

While Chinese media regularly receive guidelines from propaganda officials on “sensitive” political issues, it is rare for such instructions to be sent to financial media.

This time, the orders issued do not appear to be as severe as those issued after the cash crunch in June. Back then, Chinese media were given a written directive ordering them to “explain that our markets are guaranteed to have sufficient liquidity,” according to the FT.

During the squeeze in June, there were rumors that a bank had defaulted on a loan to another bank, but no bank confessed.

Some details of the event surfaced last week after China Everbright Bank Co. Ltd. (SHA:601818), the country’s 11th-largest bank by assets, launched what has become the biggest initial public offering in Hong Kong this year. The bank revealed that it had defaulted somewhat on 6.5 billion yuan ($1.07 billion) worth of a loan it was due to repay to another bank back in June.

According to Everbright’s prospectus issued ahead of the IPO, two of its branches “failed to receive from certain counterparties the expected proceeds from … inter-bank deposit commitments.” It didn’t name the counterparties, but suggested they might have been smaller financial institutions.

As a result of other banks’ inability to repay on time, Everbright was left cash-strapped and wasn’t able to honor its commitments to other lenders. “In order to ensure sufficient liquidity reserves, some of our branches generally obtain inter-bank deposit commitments from various local-level financial institutions on the inter-bank lending market," it said.

Liquidity is traditionally tight in China at the end of the year, a time when companies’ demand for cash rises while banks need extra cash to meet minimum deposit requirements. Analysts believe the current squeeze also reflects Beijing’s tighter stance on spending. This year’s government fiscal deposits totaled 4.5 trillion yuan at the end of November, up from 3.6 trillion last year and 3.8 trillion in 2011. Year-end government spending adds liquidity to the banking system.

With open-market operations scheduled for Tuesday and Thursday, the PBoC will most likely step in and provide more liquidity this week.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.